What SLPs Need to Know:

Agraphia

10 min read

Writing is a fundamental skill we begin learning in our early school days. As adults, we write every day for different purposes: to make notes and lists, enter events on the calendar, text our friends and family, and communicate at work. Writing, whether by hand or typing, becomes second nature for many people, requiring little mental or physical effort.

Unfortunately, writing is often negatively affected by a stroke, brain injury, and neurodegenerative conditions. This loss of writing ability is called agraphia. It can have a sudden onset or decline over time in the case of dementia. Losing the ability to write can impact communication, independence, and self-esteem. While it’s often not the first thing that brings patients to speech therapy, working to improve writing can make a big difference in quality of life.

To better understand what happens when writing goes wrong, it helps to examine how we write normally. According to the dual-route model of spelling, we use one of two ways to write or type words (Rapcsak et al., 2007):

There are also the motor and visuospatial components of writing to consider, such as forming letter shapes, spacing out words, writing in a straight line, and keyboard movements. Writing is a complex process from beginning to end, making it sensitive to brain damage.

Agraphia: A Writing Impairment

Not all agraphia types are created equal. One stems from problems with the physical act of writing, and the other is tied to language and cognition. It’s important to spot the difference in clinical practice.

Peripheral Agraphia: Impaired Motor Processes

Cortical lesions or peripheral nerve and muscle damage can result in peripheral agraphia (Tiu, 2022). It involves impaired motor planning and motor skills needed for the physical act of writing letter shapes (allographs) and typing. Peripheral agraphia is sometimes called non-linguistic agraphia, since it doesn’t revolve around the cognitive-linguistic processes needed for writing.

Someone with peripheral agraphia might write distorted letters without significant spelling errors (Magrassi et al., 2010). There are different subtypes, like apraxic agraphia and visuospatial agraphia. Occupational therapists would likely take the lead on peripheral agraphia cases, but SLPs should be aware of them to make the appropriate referrals.

Central Agraphia: Impaired Cognitive & Language Processes

Any lesion involving the cortical language areas, or their associated subcortical structures, can cause central agraphia (Tiu, 2022). Clinicians will notice errors in both oral spelling and writing since the agraphia stems from impaired cognitive and linguistic processes (Magrassi et al., 2010).

Central agraphia often coexists with other language difficulties as a symptom of aphasia. It can mimic characteristics of the spoken language impairment, like agrammatism in Broca’s aphasia or jargon in Wernicke’s aphasia, called non-fluent agraphia and fluent agraphia, respectively (Tiu, 2022). It can co-occur with an acquired reading impairment with or without aphasia, referred to as agraphia with alexia. Clinicians may encounter different types of central agraphia, keeping in mind that patients may not fit neatly into one box.

Agraphia can occur in total isolation as well, while other areas of language remain intact. This is called pure agraphia, but it’s not very common compared to the other presentations (Lees, 2022).

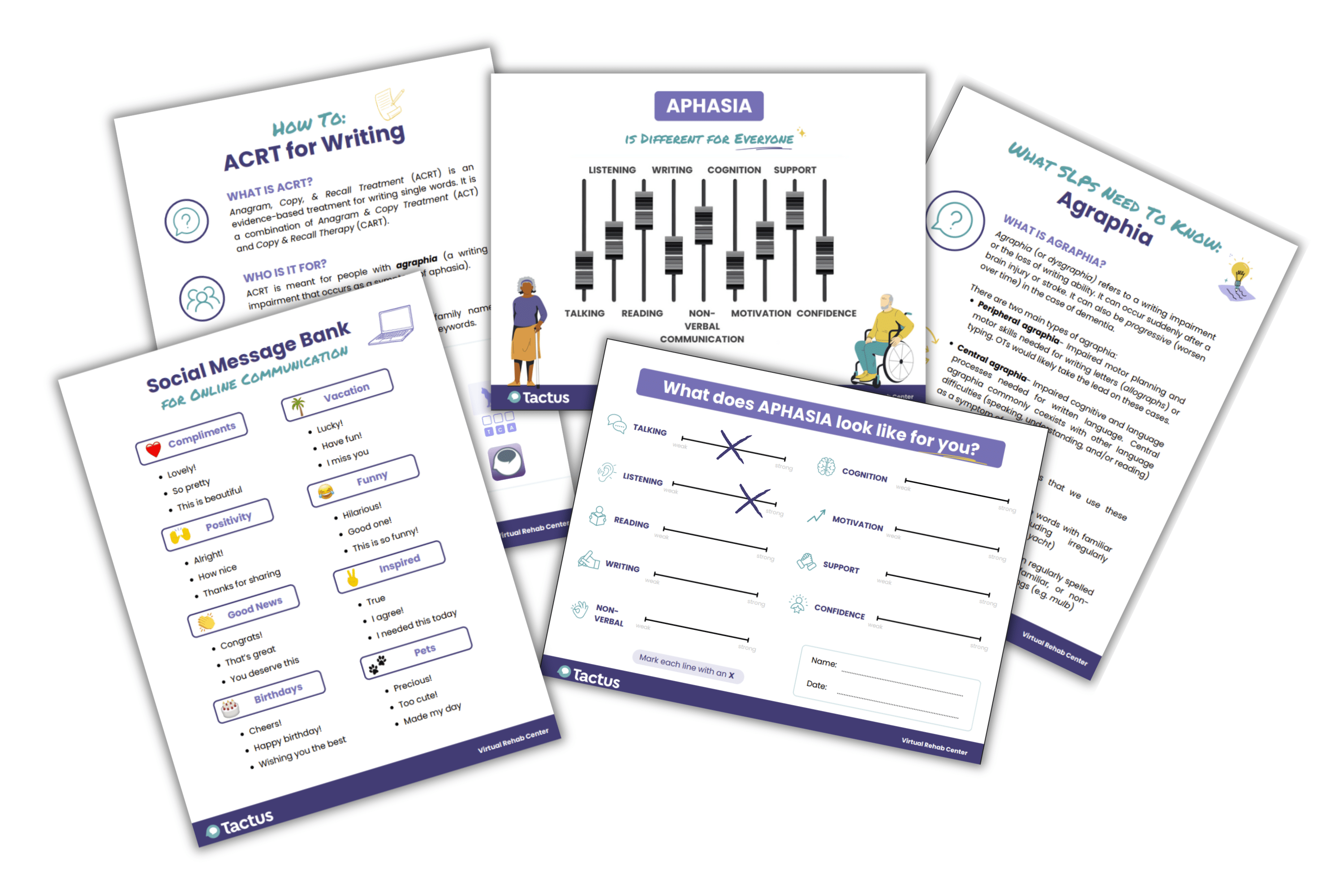

Looking for Printable Resources?

Unlock the Handout Vault

Dozens of high-quality, well-researched PDF handouts are available all in one place: The Tactus Virtual Rehab Center!

Patient education, home practice, clinical guides, visual supports, & a summary of this article for quick reference.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Access 50+ evidence-based treatments and 90+ handouts created specifically for adult medical speech-language pathologists.

Types of Central Agraphia

Thiel et al. (2013) described subtypes of central agraphia based on a cognitive neuropsychology model:

Surface Agraphia

Individuals can write regularly spelled words and non-words, like “mash” or “mult” by sounding out letters using the non-lexical route, or phoneme-to-grapheme conversion. The lexical route is impaired, meaning they can’t rely on semantics to spell irregular (yet familiar) words, like “yacht” or “knife.” You might see regularization errors, where they write a word exactly how it sounds (e.g., “yat” or “nife”).

Phonological Agraphia

Individuals can write familiar words regardless of spelling regularity. They do this by accessing word meanings via the spared lexical route. Unfamiliar words or non-words are difficult because the brain can’t pair the letters with sounds. Words with low imageability, or unclear mental representations, like the word “fact”, are harder too.

Deep Agraphia

This has the same attributes as phonological agraphia, but with the addition of semantic substitution errors. Individuals might write “pear” for “peach”, as both words belong in the same semantic category.

Graphemic Buffer Disorder

Individuals have trouble holding the lexical representations in their short-term memory while planning to write or writing out the word. This means longer words are more challenging. Common errors include letter additions, omissions, transpositions, and substitutions.

Agraphia & Electronic Communication

In an interview study by Kjellén et al. (2016), many people with aphasia said they prefer to type on a computer than write by hand, even though those with aphasia usually type slower, use less complex syntax, and have less output compared to those without aphasia (Azios et al., 2023). Writing goals often include emailing, texting, social media, and assistive technology (Menger et al., 2024). These forms of electronic communication have pros and cons for those with dystextia, a loss of texting ability or a change in texting style.

Benefits of Electronic Communication:

- More time to read, process, and formulate responses compared to voice calls

- Messages are saved to help remember conversation details

- Spelling errors, grammar errors, and abbreviations are generally acceptable; not all errors need to be corrected

- Emojis, images, and GIFs can support written messages

- Spell check, autocorrect, and predictive text can reduce errors

- Communication breakdowns are less likely

Challenges of Electronic Communication:

- Typing still requires lexical and non-lexical retrieval

- There are increased demands on spatiomotor knowledge when using a keyboard

- Texting may be more complex than handwriting

- There are different typing patterns on a phone and a computer keyboard, both requiring motor skills that might be impaired after a stroke

(Azios et al., 2023; Lee & Churney, 2022; Menger et al., 2024; Thiel et al., 2013; Beeson, 2014)

Agraphia Therapy for Technology:

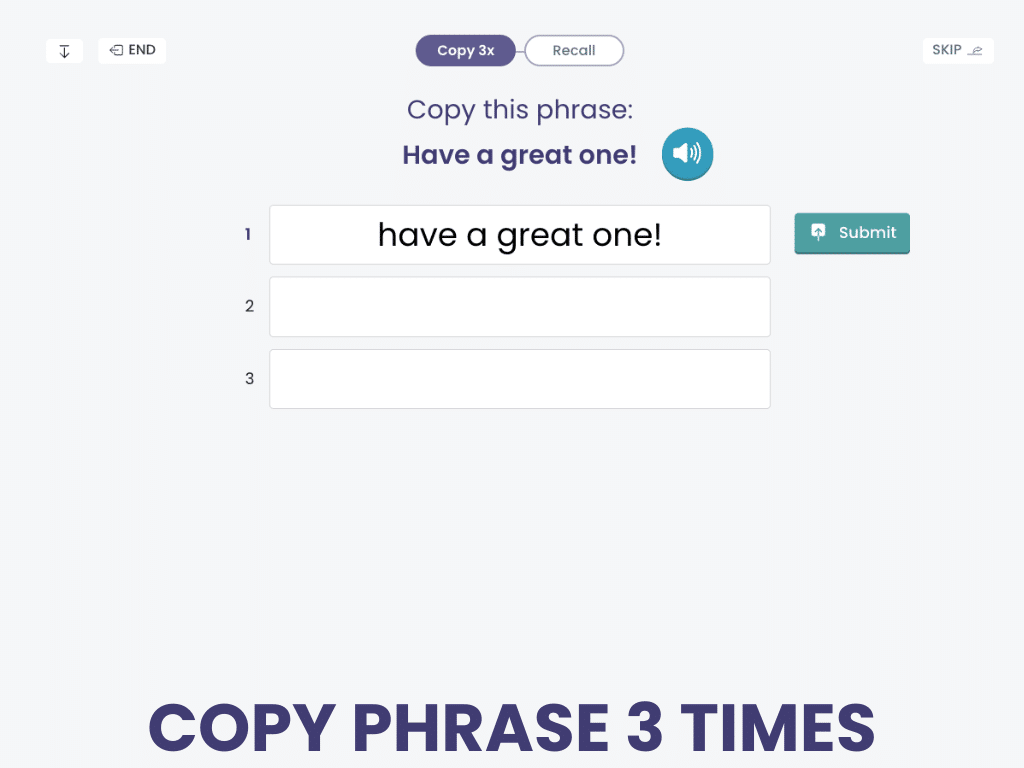

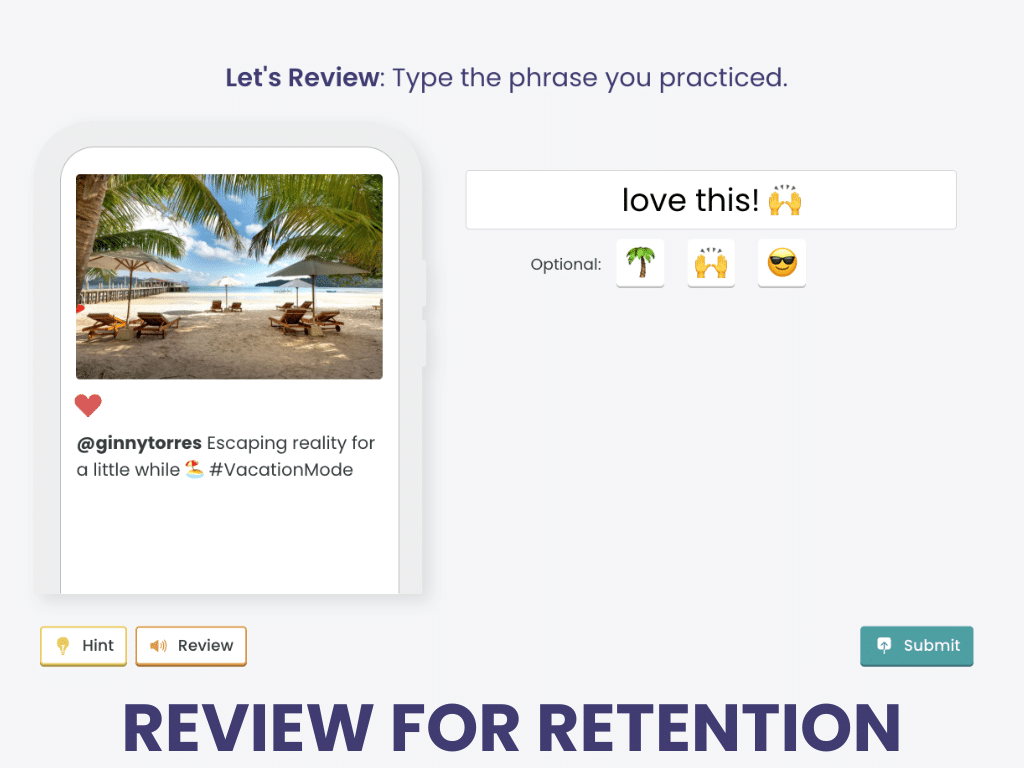

Copy & Recall Social Messages

Copy & Recall Social Messages uses functional stimuli to help people with agraphia learn common phrases used in texting and social media.

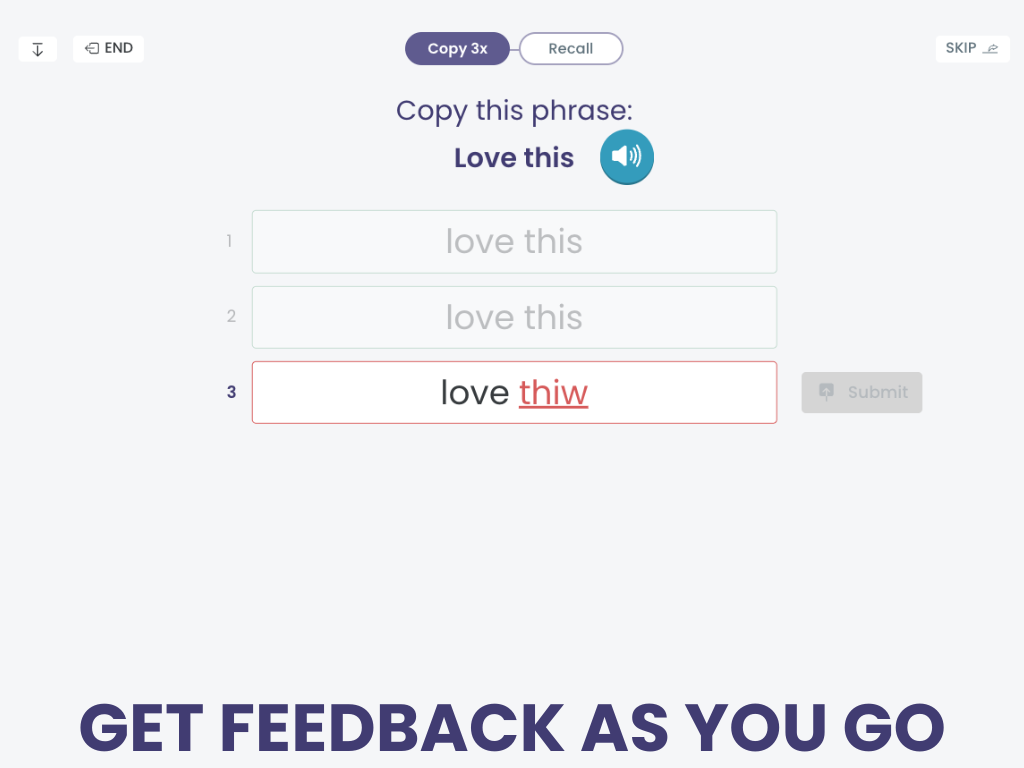

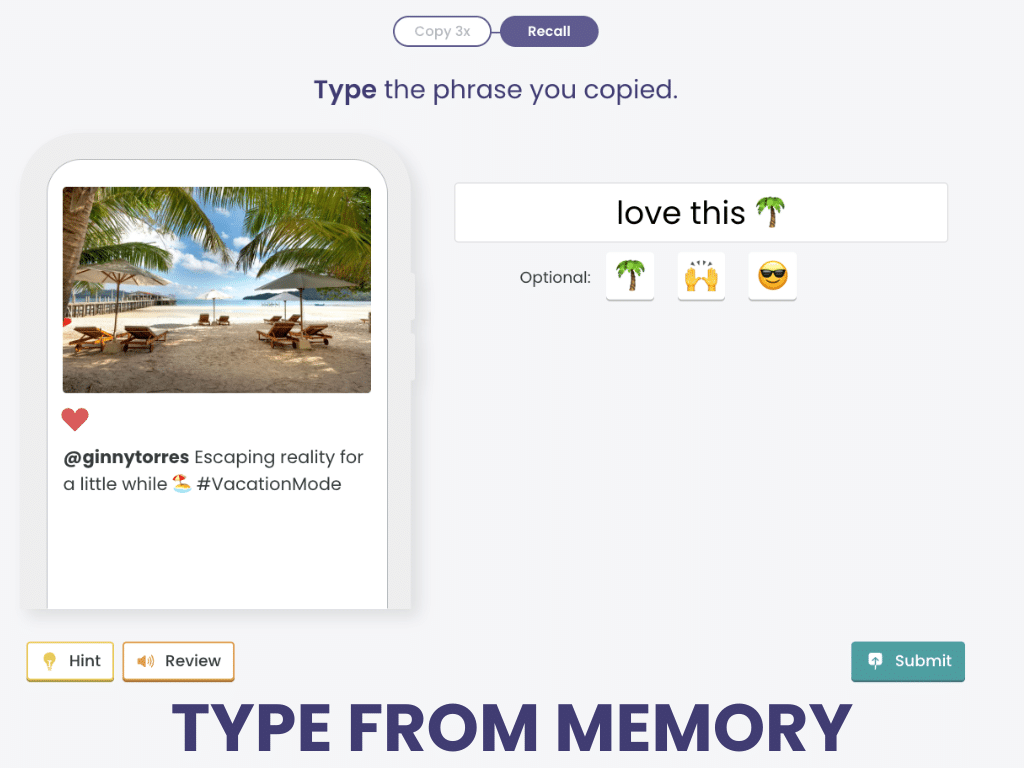

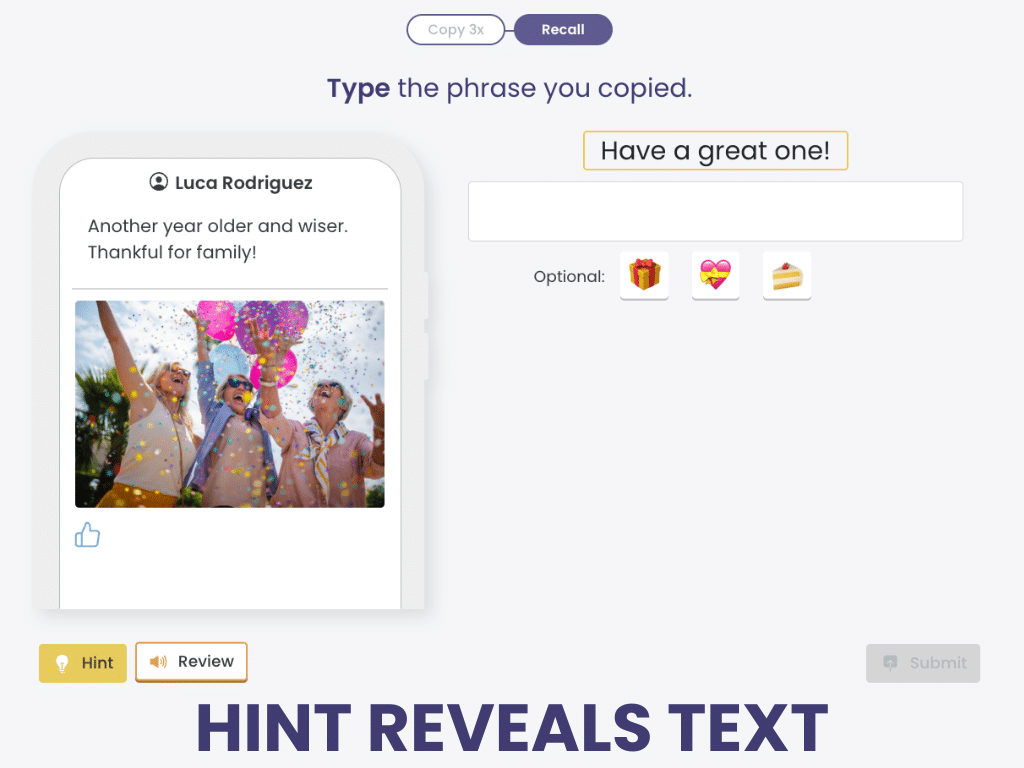

Copy 3 times, then recall from memory, reviewing every few trials for better retention. Add emojis and likes for fun!

Copy & Recall Social Messages is a writing treatment in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Use technology to present stimuli of just the right difficulty, provide feedback, adjust complexity, and score the performance – even write the SOAP note!

Assessing Agraphia

A sudden shift in writing abilities can impact self-esteem, confidence, and inclusion in society (Thiel & Conroy, 2022). It can also affect participation in day-to-day activities. As clinicians, we know how important it is for patients to maintain as much independence as possible. This is why it’s important to discuss patients’ writing needs and goals during the initial assessment. Start by asking simple questions like:

- How do you use writing in your daily life?

- Is texting/emailing important to you?

- Do you use social media often?

- How happy are you with your handwriting/typing skills now?

- What changes have you noticed since your stroke?

- Which areas do you want to improve?

Obermeyer et al. (2023) used an 11-item computer usage questionnaire, which could be useful to clarify typing difficulties post-stroke. It includes questions like, “How many hours are spent on the computer pre/post stroke?” and “Do you prefer to handwrite or type grocery lists?”

Once you’ve narrowed in on the patient’s needs, you can administer other measures to assess writing. Use the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB-R Writing), or take advantage of free options like the Arizona Battery for Reading and Spelling (download the ABRS here) or the Digitised Assessment for Aphasia of WritiNg (DAAWN). Think about the underlying cause of writing difficulty: is the lexical or non-lexical route damaged? Consider how performance on single-word tasks differs regarding:

- Oral spelling vs. handwriting

- Regularly vs. irregularly spelled words

- Real vs. non-words

- Short vs. long words

- High- vs. low-frequency words

- Imageable vs. non-imageable words

Consider collecting a handwritten or typed discourse sample to analyze correct information units, or CIUs. You can use pictures from the Nicholas and Brookshire article (1993) and prompt patients by saying, “Look at these six pictures and write what is happening” (Obermeyer et al., 2023).

Lee & Cherney (2022) developed the Texting Transactional Success rating scale (TTS) to assess how patients convey information during text exchanges. It is a 3-point scale: award no points for an unsuccessful transaction, 1 point for a partially successful transaction, and 2 points for a successful transaction. Based on pre-treatment ratings of text exchanges, identify transactional strategies and practice them during treatment to increase the patient’s success. Strategies include:

- Copying and pasting

- Using multimedia content (e.g., emojis, photos, GIFs, web links)

- Self-repairing

Treating Agraphia

Multiple therapy protocols involve some combination of anagramming, copying, and recalling words. This lexical-semantic approach can improve written naming for trained words.

Target words for these treatments should be functional and personally relevant, since generalization to untrained words is limited based on research findings.

Writing Words in Steps:

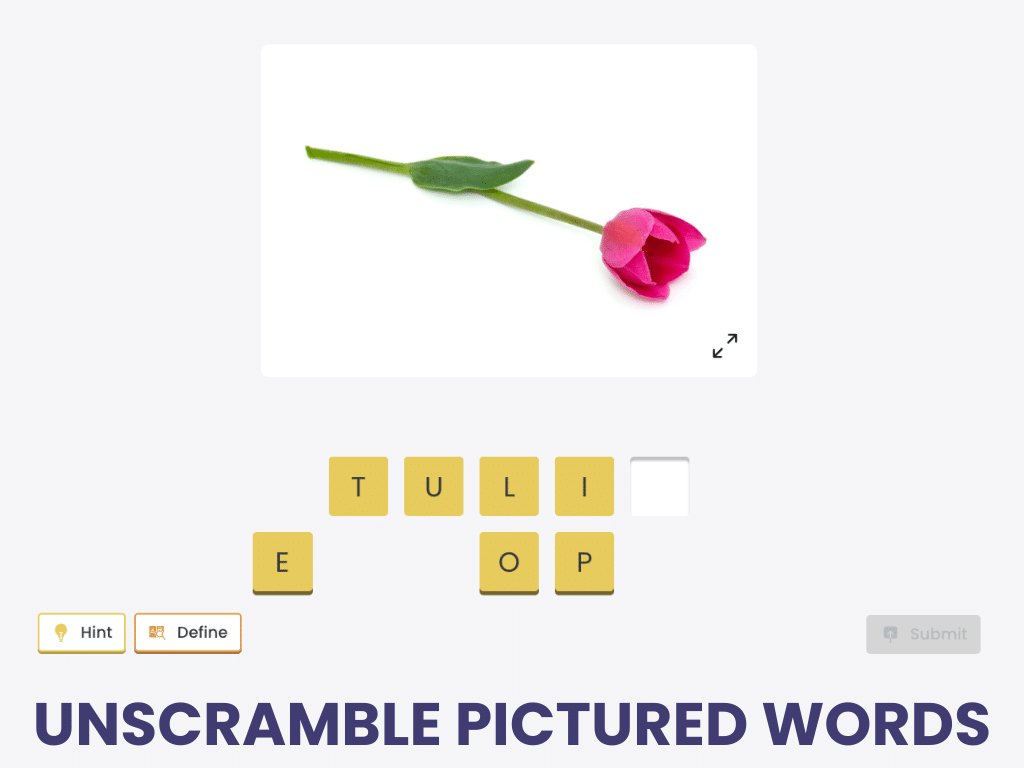

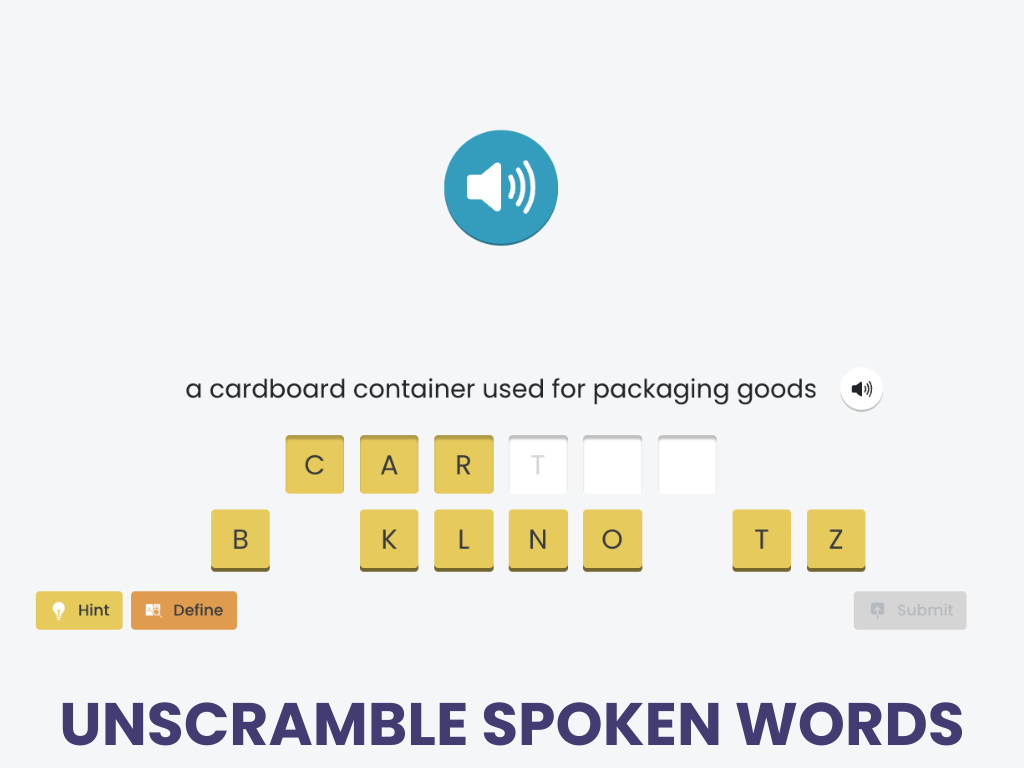

Anagramming Treatments

Unscrambling Pictured Words & Unscrambling Spoken Words are 2 treatments in the Virtual Rehab Center that work on anagramming.

Each treatment has 12 levels of difficulty, focusing on 3, 4, 5, and 6+ letter words, given 0, 2, or 4 extra letters as distractors.

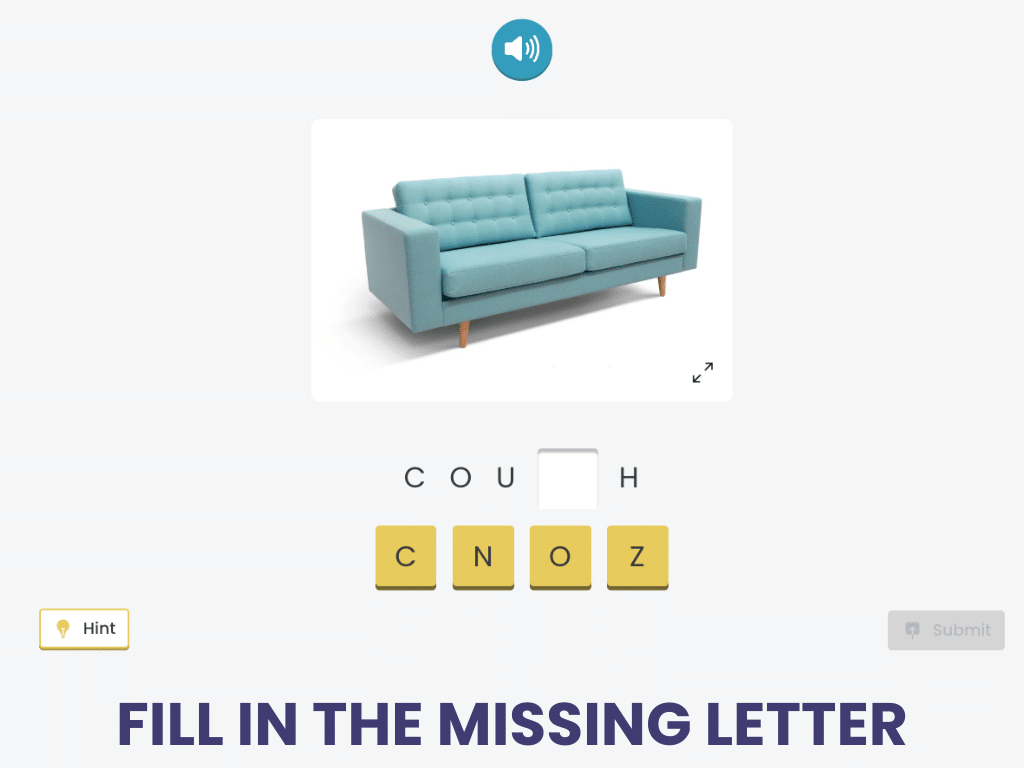

Filling in the Missing Letter and Typing in the Missing Letter are two simpler treatments in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center. Practice pre-anagramming skills across 12 levels of difficulty.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

We know that regaining writing skills can take time. That’s why we offer so many different writing treatments to meet you where you are right now.

A phonological approach can be used if the sublexical route (or the phoneme-to-grapheme conversion) is impaired. Sound-letter and letter-sound correspondences are trained using a hierarchical approach described by Beeson et al. (2010). Studies have found improved phonological processing and spelling using this phonological approach.

Learn more about the phonological approach in this How-To article.

For patients with milder deficits, these treatments target writing at the sentence level:

If a patient can write at the sentence level but struggles with longer passages, consider using assistive technology in your sessions. Moss et al. (2024) had patients with acquired agraphia use speech-to-text and text-to-speech software for 7-10 hours weekly. They found significant improvements in narrative writing and social networking after training. Gains didn’t generalize to handwriting, suggesting this approach can help patients compensate for writing deficits but doesn’t restore skills.

Writing Words in Steps:

Copying Treatments

Copying Single Words and Typing Single Words are 2 treatments in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center to work on copying.

One uses letter tiles, while the other uses a keyboard. Both can then be practiced on paper using a pen or pencil.

Once copying has been mastered, use Typing Pictured Word or Typing Spoken Words for agraphia rehabilitation.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

These treatments have 12 levels of difficulty based on word length and spelling regularity, to target both the lexical and non-lexical routes.

Final Thoughts on Agraphia

Understanding the lexical and non-lexical routes for spelling is the first step in assessing and treating writing difficulties. Identifying specific impairments and the patient’s personal writing needs can help clinicians choose a treatment approach. With the right support, individuals with agraphia can rebuild their writing skills, restoring both confidence and independence.

Learning More about Agraphia

We used many references to bring you this information, all linked where cited. We recommend these selected sources for a good overview:

- Menger, F., Wilkinson, V., & Webster, J. (2024). Write here write now. what can we learn from the writing goals of people with aphasia? Aphasiology, 1–18.

- Rapcsak, S. Z., Henry, M. L., Teague, S. L., Carnahan, S. D., & Beeson, P. M. (2007). Do dual-route models accurately predict reading and spelling performance in individuals with acquired Alexia and Agraphia? Neuropsychologia, 45(11), 2519–2524.

- Thiel, L., & Conroy, P. (2022). ‘I think writing is everything’: An exploration of the writing experiences of people with aphasia. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 57(6), 1381–1398.

Cite this article: Shahid, S. (2025, May). What SLPs Need to Know: Agraphia. Tactus Therapy. https://tactustherapy.com/treating-agraphia-writing-speech-therapy/