Get Talking: Using Conversation to Help a Stroke Survivor Overcome Aphasia

6 min read

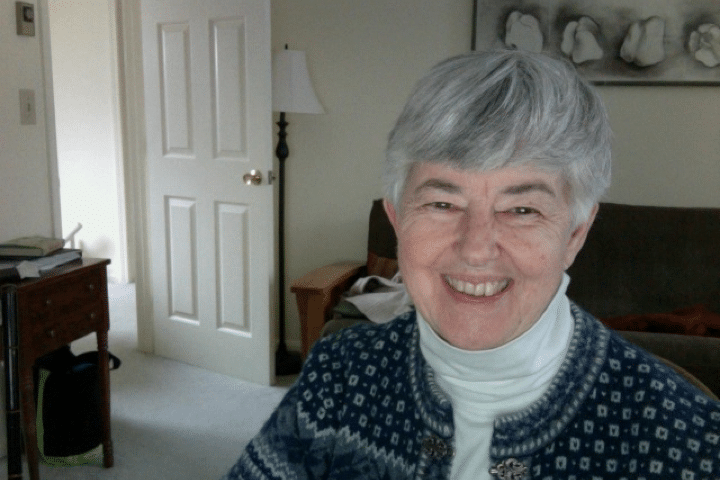

Three months shy of her planned retirement, Barbara’s life took a detour. Days that she once imagined would be filled with visiting her children in other states and pursuing her art and music interests were now entrenched with hospital visits, multiple rehabilitation sessions, and frantic online searches for answers.

It was March of 2010 when Barbara’s husband, Stephen, had a stroke.

“It was early in the morning, 6 or 6:30, and we were at home getting ready for work,” Barbara recalls. “Stephen had gone downstairs before me, and when I came down I found him on the floor. He was sitting there and just kept moving his glasses off and on his face.”

Stephen had suffered an ischemic stroke caused by an artery dissection, which is a separation of the layers of the artery wall that supplies oxygen-bearing blood to the brain. This diagnosis wasn’t considered when Stephen arrived at the hospital, however. It’s the most common cause of stroke in young adults, and Stephen was 63.

Stephen was treated for 10 days at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, the major tertiary-care referral site in the region, before he was transferred to a rehabilitation center. His medical insurance allowed for a few months of inpatient rehab therapy in two different facilities before he was sent home.

In addition to right-side paralysis, which is common for stroke survivors, Stephen was diagnosed with severe aphasia and severe apraxia, conditions that affected his ability to communicate and to point to what he wanted.

Aphasia is an impairment in the ability to produce and/or to comprehend language. It ranges from difficulty finding words to being unable to speak, understand, read, and/or write.

Apraxia is an impairment in the ability to execute complex coordinated movements, despite having the desire and the physical capacity to perform the movements. It often affects movements of the arm, hand or mouth.

The Same, But So Different

For many, thoughts of going home provide comfort—the familiarity of a favorite chair, recollection of a special occasion, established routines. In their small rural town in New Hampshire, nothing would be the same again for Stephen and Barbara.

Stephen, a college administrator and published author, was a real extrovert who loved to talk. Barbara fondly recalls that he was the entertainer at social gatherings. The changes caused by his stroke were devastating. Even the rural area they loved now presented barriers to Stephen’s mobility.

Given her background and the new knowledge she was picking up about the neuroplasticity of the brain, Barbara was determined to try everything she could think of, that Stephen would agree to, not just for speech but for every aspect of his recovery. She recruited help wherever she could find it—online therapists, speech-language consultants, in-home therapists, and caregivers. She and Stephen even traveled to Canada for a five-week intensive aphasia program.

“It’s about trial and error,” Barbara explains. “It’s frustrating because you’re so vulnerable. You’ll do anything for hope. It comes down to trying different things and looking for progress.”

Finding the Right Tools

While Stephen may have benefitted in some measure from every approach, Barbara feels that stimulating conversation and speech therapy apps had the most impact on his aphasia and apraxia.

It all started with a book she found online.

The Teaching of Talking: Learn to Do Expert Speech Therapy at Home With Children and Adults demonstrates how loved ones and caregivers can provide effective speech and language stimulation during daily activities. Author Mark A. Ittleman, a speech-language pathologist, uses an interactive, conversational method. He recommends that friends and family members encourage stroke survivors to talk all through the day while they’re doing things together.

“We hired the author to help us put the lessons in the book into practice, and had about 25 sessions with him over six to eight months,” Barbara says. “It’s a simple method—very teachable. It’s about stimulating conversation in everything you say and do. Basically, I ask questions that can be answered with a yes or no, but then I cue him to answer with a complete sentence, largely using the words I used in the question. I help him, including mouthing the words with him, when he is responding. The idea is to get him engaged and expecting himself to answer with a complete sentence. It helps his brain to work on his own complete sentences without necessarily always being cued. And this is working as he does frequently now come out with his own sentences.”

Barbara’s career as an English teacher, guidance counselor, and special education teacher made her a natural fit for this approach. But she warns that it’s may not be for everyone. It takes practice and some people with aphasia may not respond as well to the method, for a variety of reasons.

“It just really worked for us. But I see how it could be difficult for some, and certainly isn’t for everyone.”

Over time, Barbara found that she struggled to find new things to talk about. “The intention is to weave language stimulation into talking about the person’s passions and what they’re doing every day,” she explains. “But my husband prefers to stay home, and with his right-arm paralysis, he isn’t able to do many of the things he took an interest in before. Even the church he once attended isn’t accessible.”

Barbara turned to several speech therapy apps from Tactus Therapy to support her efforts. She especially likes Conversation Therapy.

“The pictures offer strong visual stimuli,” Barbara explains. “We don’t always use the actual wording in the questions, but they prompt us to create sentences of our own. Sometimes we actually digress to having a conversation on an entirely different subject. It’s great when we don’t have to work hard at making conversation.”

Stephen also uses Writing Therapy, Reading Therapy, and Naming Therapy (all part of Language Therapy 4-in-1) as part of his program at home.

“Other than Conversation Therapy, which is about two people talking, he can use these tools independently,” Barbara says.

Getting Help

It’s been four and a half years since Stephen had his stroke. He now walks around the house with a cane, and uses a powered wheelchair on the rare occasions when he goes outdoors. His aphasia is primarily expressive, though Barbara thinks he occasionally misses things people say. He still doesn’t use his right hand, even though he shows some evidence of muscle control during physical therapy.

“To see where Stephen is now and has been for quite a while, he often says, ‘I’m better!’ But it’s not good enough.”

Barbara’s therapy methods are now largely supported by two caregivers who each spend three to five hours on alternate days working with Stephen. She also looks for other approaches to speech-language and physical therapy that she can share with the caregivers.

“It’s good for Stephen that he has other people to talk with and interact with,” she says, crediting the caregivers with introducing new subjects and materials. “It’s also about stimulating him intellectually, emotionally, and socially. One of the caregivers, for example, was showing pictures from his vacation, which Stephen really seemed to enjoy.”

Barbara knows she’s lucky to be able to afford professional support for Stephen and for herself. Getting out for a few hours a day enables her to stay active in her church, maintain an exercise program, and do some shopping without worrying about Stephen.

Carving out time for herself benefits both of them. “Stephen likes the fact that he doesn’t feel like a burden,” she says. “I’m unusually fortunate that life is really this good.”

Still, he’s never too far from her mind. “I know he walks less when I’m not at home,” she says, “so even though he’s safe and well, I’m always quick to get back to him.”