What SLPs Need to Know:

Clinical Swallow Evaluation

10 min read

Assessing dysphagia is one of the most essential skills as a medical speech-language pathologist, but it is also one of the most intimidating. With the release of updated studies, methods, and tools every few years, it can be challenging to stay current. There are also practice differences across settings and clinicians; however, as a field, we are moving towards greater consistency. For this to continue, clinicians must be open to learning.

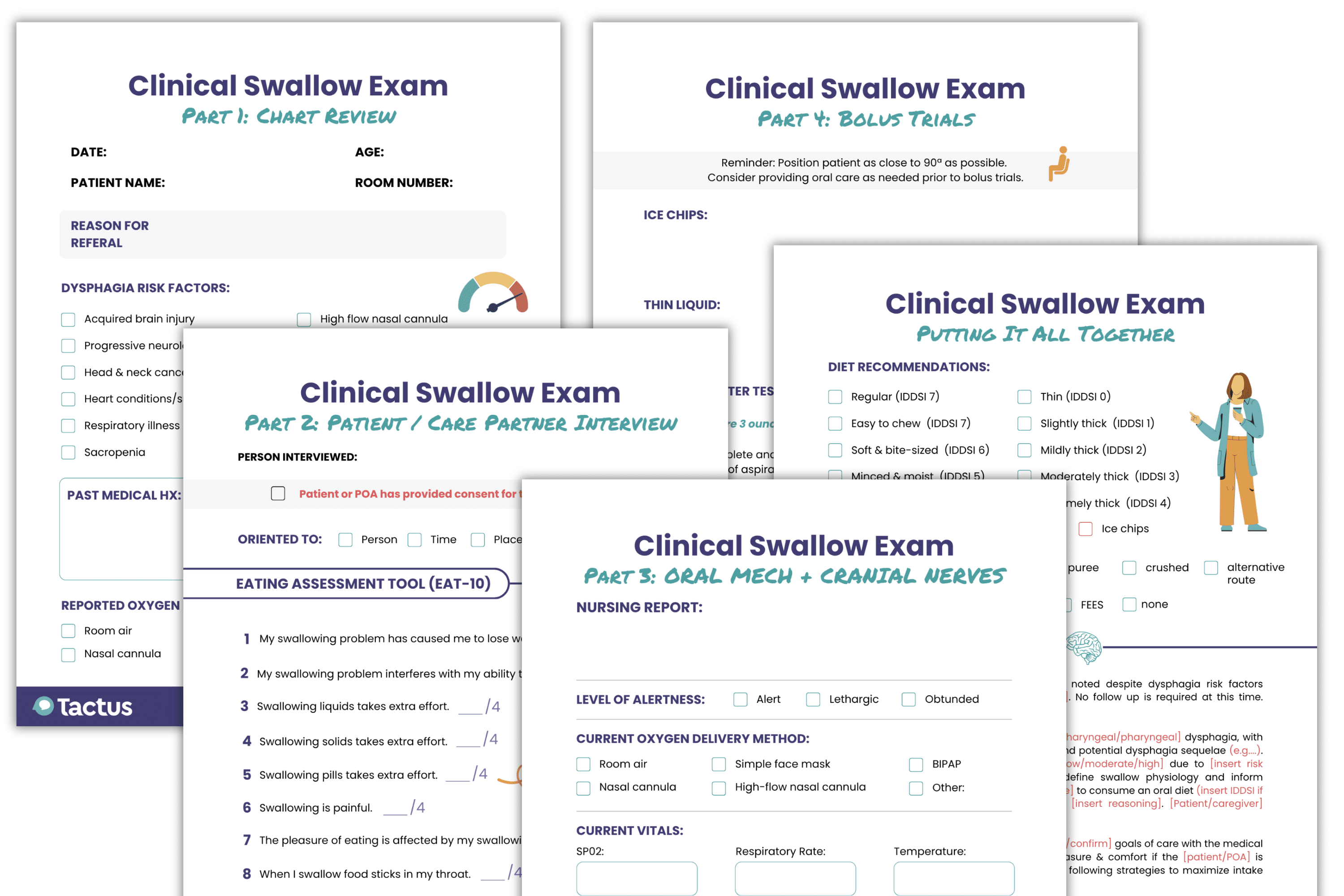

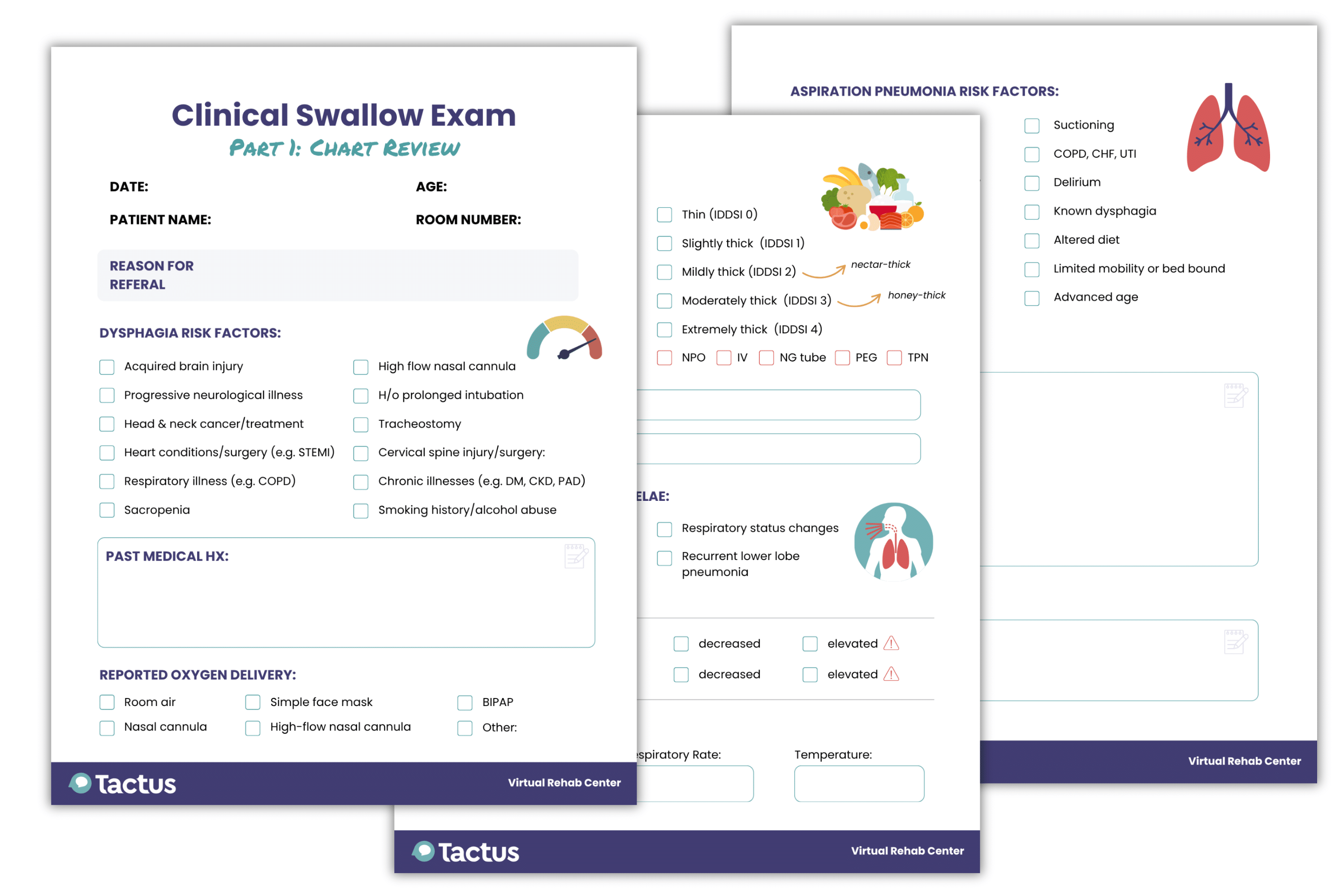

The clinical swallow evaluation (CSE), also known as a bedside swallow exam, involves critical thinking to estimate swallow ability and the extent of the swallowing problem (Carnaby, 2012). A typical CSE has four main parts:

- Chart review

- Patient and/or care partner interview

- Cranial nerve and oral mechanism exam

- Oral trials (if appropriate)

Together, these steps help SLPs differentiate between patients who have a functional swallow and those who require further testing with an instrumental assessment. The CSE has many limitations; the clinician cannot directly visualize the larynx or pharynx during a bedside exam. That means it’s impossible to determine if the swallow is delayed, if laryngeal elevation is reduced, or if aspiration is occurring solely by observing the patient or palpating the neck. For this reason, instrumental tests, such as a modified barium swallow study (MBSS) or fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), are often essential.

Get the ultimate CSE guide!

Download yours in the Virtual Rehab Center

Get a 14-page step-by-step guide through all 4 steps of the CSE inside The Tactus Virtual Rehab Center!

These beautiful printable forms are invaluable for students, new grads, and new-to-dysphagia clinicians.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Access 50+ evidence-based treatments and 90+ handouts created specifically for adult medical speech-language pathologists.

CSE Part 1: Chart Review

Learning to extract relevant information from a medical record is crucial when completing an informed assessment of swallowing abilities. SLPs should pay attention to:

- the reason for referral

- the history and physical (H&P)

- previous and current diet orders

- allergies

- interdisciplinary reports (e.g. nursing, dietary, GI, ENT)

- recent lab work

- diagnositic imaging (e.g. chest x-ray, chest CT, previous MBSS or FEES reports, esophagram, laryngeal endoscopy)

- recent vitals

History and Physical

The H&P provides an overview of the patient’s relevant medical history, surgical history, and the present illness. SLPs need to familiarize themselves with common terminology to expedite this process. (See this list of common medical abbreviations provided by ASHA.)

Make a note of any pre-existing diagnoses or current conditions that would raise the risk of dysphagia. Some common risk factors include:

- acquired brain injury (e.g. stroke, TBI)

- progressive neurological disease (e.g. Parkinson’s dementia, ALS)

- head and neck cancer and treatment (Patterson & Lawton, 2023)

- heart conditions and surgical treatment (Velasco, 2025; Plowman et al., 2023)

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Lin & Shune, 2020)

- sarcopenia, the loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function (Chen et al., 2021)

- history of smoking or alcohol abuse (Dua et al., 2009)

- prolonged intubation (Hou et al., 2023)

- presence of a tracheostomy tube (Bailey, 2005)

- specific oxygen delivery methods like the high-flow nasal cannula (Sutt & Wallace, 2025)

- cervical spine surgery (Alentado et al., 2023)

- diabetes mellitus, liver disease, kidney disease, or peripheral arterial disease (Karisik et al., 2024)

Keep an eye out for possible dysphagia sequelae in the H&P or interdisciplinary reports, like unintentional weight loss, malnutrition, dehydration, change in respiratory status, and recurrent lower-lobe pneumonia.

Remember: just because a patient is at risk for dysphagia and presents with clinical signs, it does not mean they will automatically get aspiration-related pneumonia. Part of the SLP’s job is to identify risk factors for aspiration pneumonia, as discussed by Langmore and colleagues (1998). Ask yourself:

- Are they dependent for feeding or oral care?

- Do they have poor oral health or decayed teeth?

- Are they a current smoker?

- Do they receive non-oral nutrition? (i.e. tube feeding)

- Are they taking multiple medications?

- Do they have multiple comorbidities?

Langmore et al. (2002) identified other risk factors in nursing home residents, like suctioning, COPD, CHF, bedbound, delirium, weight loss, swallowing problems, urinary tract infections, altered diet, mobility, and age. Most of this information can be found in the patient’s chart. Other factors, such as oral health, can be assessed at the bedside using the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT).

Lab Reports

Specific lab values, such as markers for nutrition, hydration, and infection, can influence clinical decision-making. For example, an elevated white blood cell count (WBC), also known as leukocytosis, can indicate an inflammatory response somewhere in the body (Sheffler, 2015). An elevated neutrophil count can point to a bacterial infection. If a patient presents with these findings, along with aspiration-related features on chest imaging, they could have aspiration pneumonia.

Diagnostic Imaging

There are a few key terms to look for on a chest X-ray that may be suggestive of aspiration, such as infiltrate or consolidation in specific lung areas.

An infiltrate represents the buildup of substances or cells in the airspaces of the lungs. Infiltrate locations can be informative (Sanivarapu et al., 2024):

- Right lower lobe: most commonly linked to aspiration pneumonia

- Basal segments of lower lobes or right middle lobe: more likely if the patient is mostly upright

- Superior segments of the lower lobes or posterior upper lobes: more likely in bedbound patients

- Left lobes: possible for patients who aspirated while lying on the left

Consolidation is another keyword that could be tied to aspiration. It occurs when a region of the lungs contains an infiltrate instead of air, resulting in hardening or swelling of the tissue. Consolidation in gravity-dependent lung zones could be concerning.

According to an observational study, pneumonia is only correctly identified on a chest X-ray about 70% of the time (Laursen et al., 2013). A chest CT is actually more specific and sensitive when it comes to diagnosing aspiration pneumonia (Garin et al., 2019; Khan, 2021).

Vitals

Patient vitals provide valuable insight into the patient’s stability and readiness for a swallowing exam.

- Normal respiratory rate is between 12 and 20 breaths per minute. Learn how to measure respiratory rate here. If the respiratory rate is very high, the patient is probably not appropriate for oral trials.

- Normal oxygen saturation (SpO2) is between 95% and 100% for healthy adults, but can be lower if the patient has a chronic respiratory illness. Breathing always takes priority over swallowing, so the CSE will have to wait if the oxygen reading is concerning.

- Normal body temperature ranges between 97°F and 99°F (36.1°C and 37.2°C). A temperature of 100.4°F (38°C) or above is considered febrile and may be a possible marker of infection.

Nurses often have the most current and detailed information about the patient’s condition, so checking in with them before the assessment can help guide the CSE in the right direction.

CSE Master Guide Part 1:

Chart Review

Part 1 of the CSE Master Guide takes you through the all-important chart review.

Check off dysphagia risk factors, note important lab values, and highlight the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Download your free copy today inside the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs & access all the handouts!

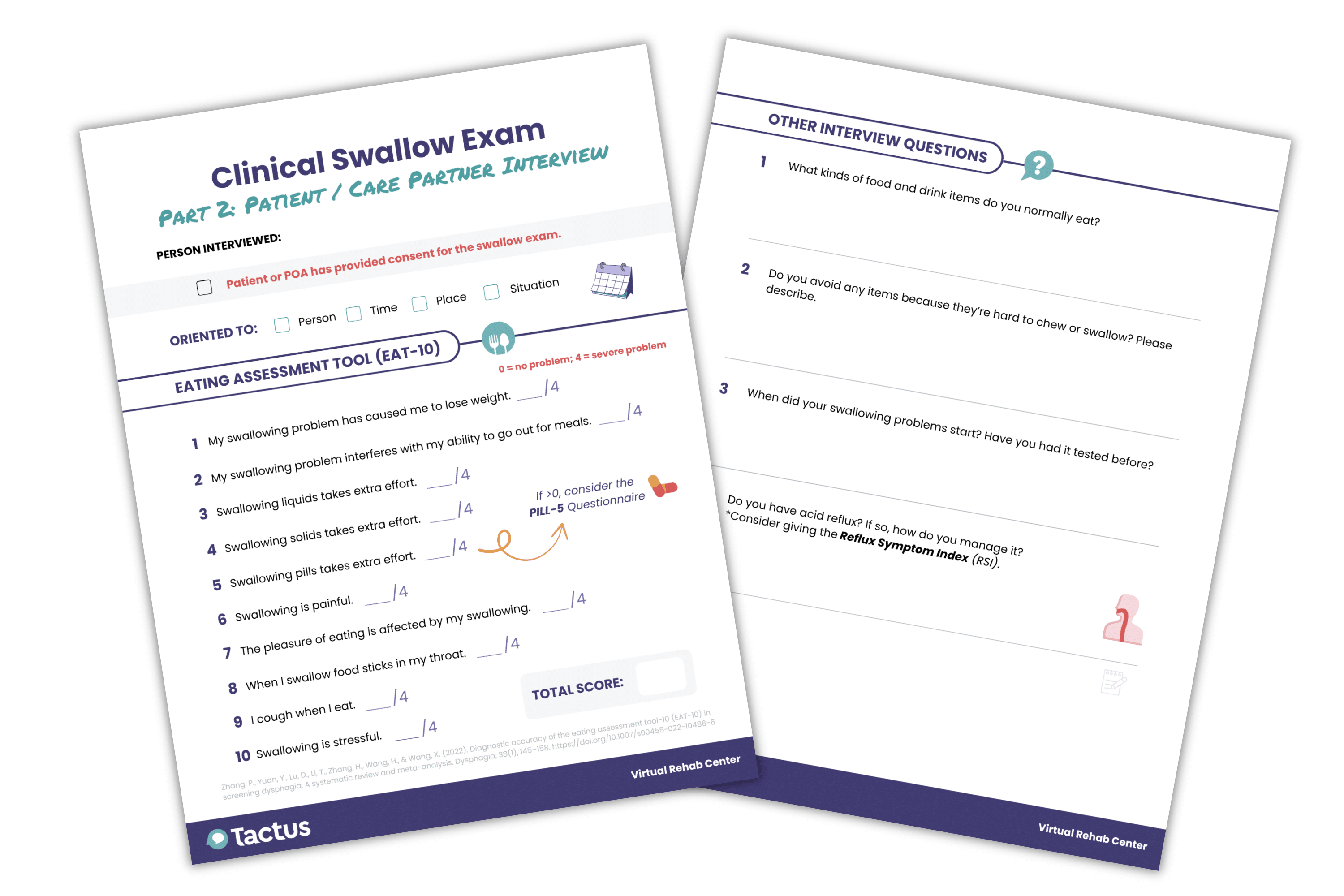

CSE Part 2: Patient Interview

A patient or care partner interview provides valuable insights that testing alone cannot capture. This conversation helps build a clearer picture of the patient’s swallowing history, daily routines, food preferences, and any recent changes in function. It also creates an opportunity to establish rapport and involve the patient and family in the assessment process.

Begin by making the patient comfortable: introduce yourself, explain the purpose of your visit, and obtain consent for the evaluation. Take a moment to observe the patient’s level of alertness and ask simple orientation questions. This not only helps gauge cognitive status but also sets the tone for a supportive and collaborative interaction.

The specific interview questions will depend on the patient’s situation. You can use a free patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) to help measure patients’ subjective swallow difficulty:

CSE Master Guide Part 2:

Patient / Care Partner Interview

Part 2 of the CSE Master Guide takes you through the patient interview, ensuring you won’t forget what to ask.

We’ll help you know when to use other PROMS based on responses, too!

Includes the 10-question Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) patient-reported outcome measure.

Get this and dozens of other patient education handouts along with evidence-based treatments in the Virtual Rehab Center.

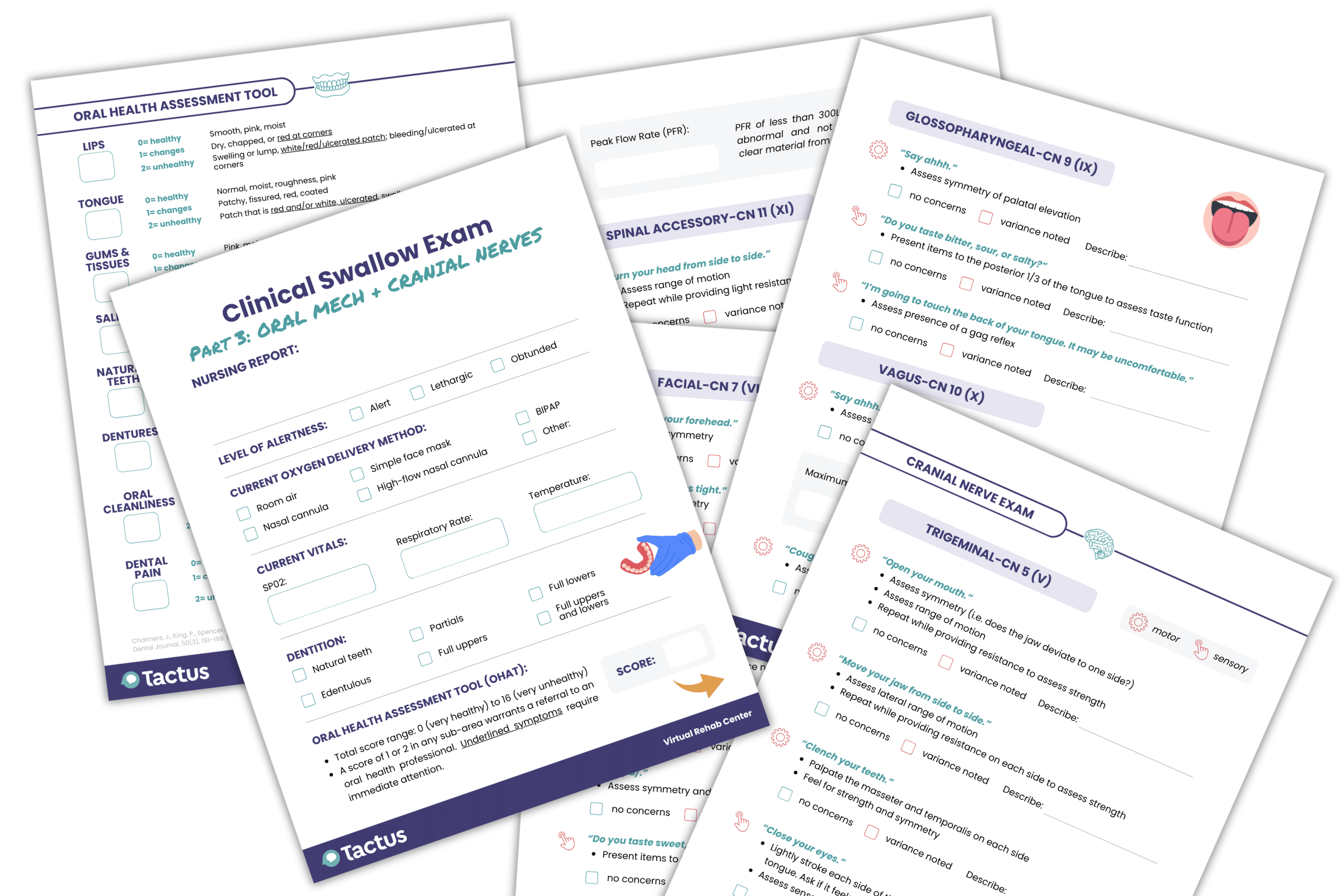

Part 3: Cranial Nerve & Oral Mechanism Exam

There are five cranial nerves involved in the swallowing process that should be examined during the CSE (Carnaby, 2012):

Nordio et al. (2025) found that impairment of CN VII can help predict vallecular residue, and CN V and CN X can predict pyriform sinus residue. This finding confirms the importance of assessing cranial nerves during the CSE.

Generally, you will observe:

- facial symmetry

- jaw strength and range of motion

- tongue strength and range of motion

- lip seal and range of motion

- sensation of various facial structures

- vocal quality (PDF), maximum phonation time, and pitch elevation

- voluntary cough (see below)

Evaluating Cough Response

It’s valuable to get an objective measurement of cough strength to see if it’s strong enough to potentially eject aspirated material. SLPs can use a peak flow meter to measure how quickly the patient can expel air from their lungs. The device will provide a Peak Flow Rate (PFR) that can be compared to normative values. A PFR of less than 300L/min is potentially abnormal (Borders & Troche, 2022) and not strong enough to clear material from the airway.

CSE Master Guide Part 3:

Oral Mech & Cranial Exam

Part 3 of the CSE Master Guide is one you’ll want to laminate and use over and over.

Step-by-step instructions for assessing each relevant cranial nerve with exactly what to say & what to look for!

Integrates the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) right on the form for easy scoring of the oral mech exam.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

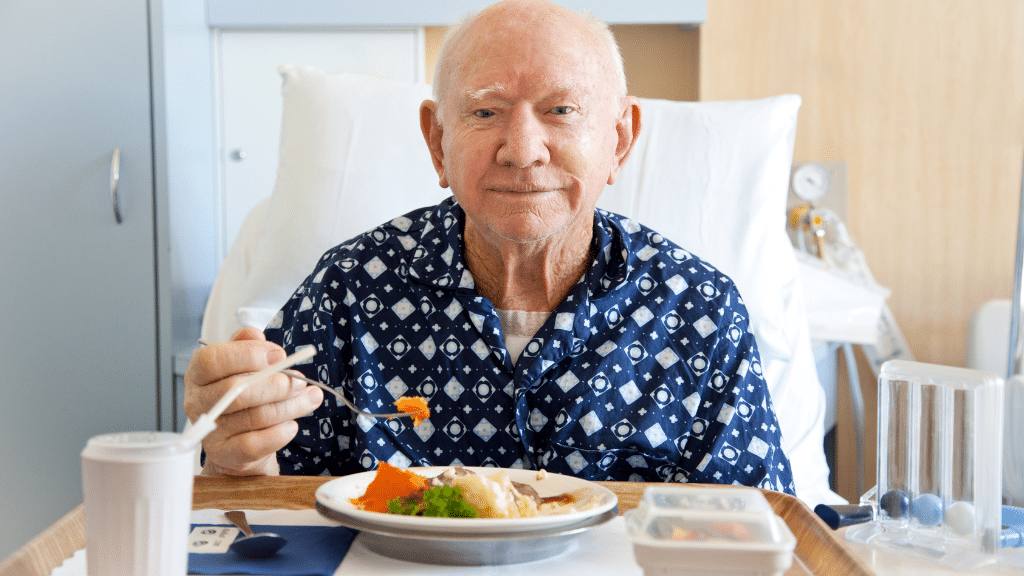

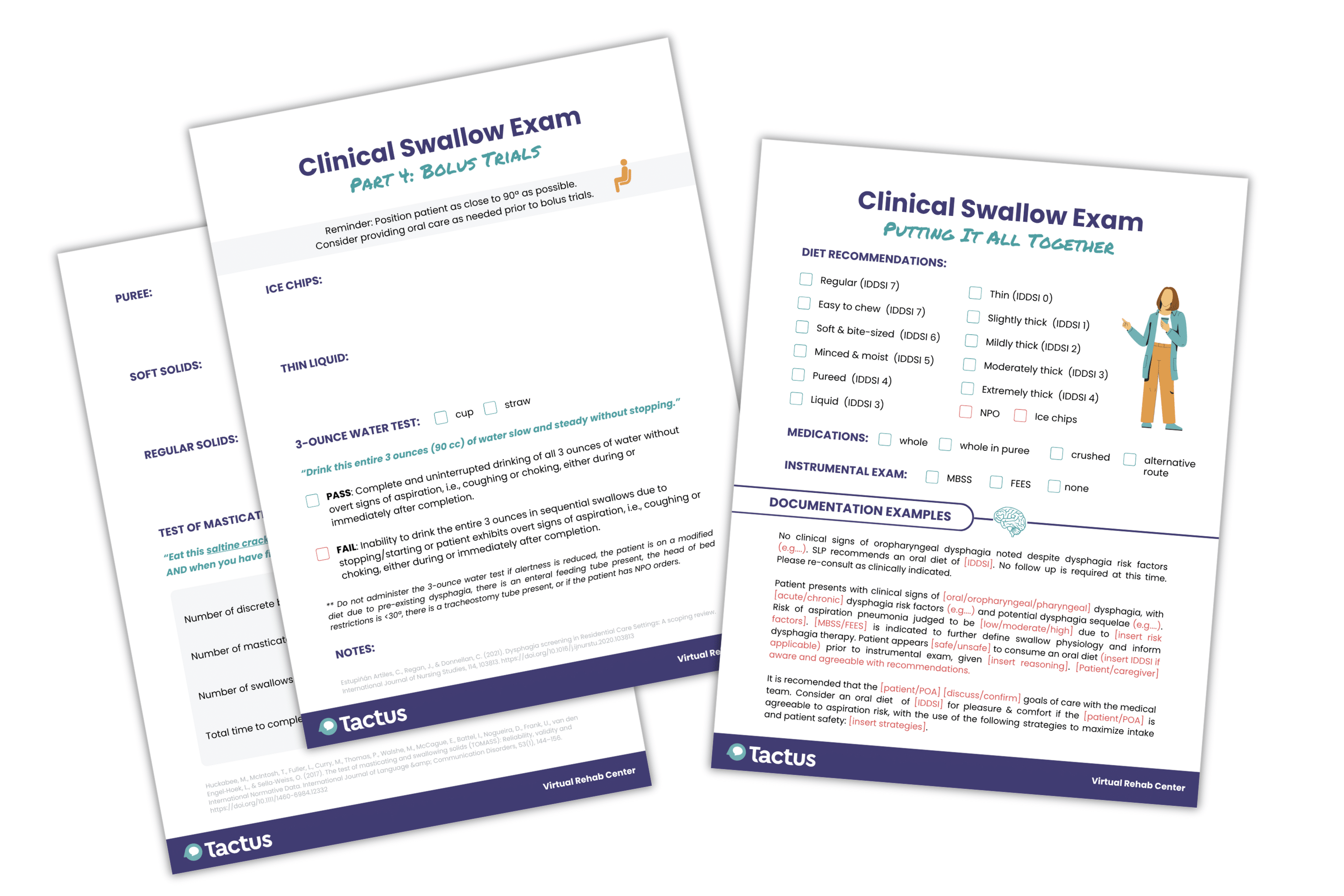

Part 4: Oral Trials

If a patient is not very alert, unable to manage their own secretions, or has a history of silent aspiration, they are not appropriate for bolus trials. Trials can be deferred in favor of an instrumental assessment in critically ill patients with high aspiration risk.

If trials are appropriate, begin by positioning the patient as upright as possible, with assistance from care staff if needed. It’s good practice to provide oral care beforehand, both for comfort and safety.

During trials, offer small, controlled amounts of different consistencies, such as ice chips, thin liquids, pureed solids, soft solids, and regular-textured solids. Make note of any oral difficulties, including poor containment, pocketing, or residue, as well as overt signs of aspiration.

In the past, it was common practice to thicken liquids at the bedside if a patient showed signs of aspiration with thin liquids. However, many clinicians are moving away from this approach for several reasons (McCurtin et al., 2024). Research shows that thickened liquids are actually more likely to be silently aspirated than thin liquids (Miles et al., 2018). A recent systematic review also linked thickened liquids to several adverse effects and events, including reduced quality of life, decreased intake, dehydration, urinary tract infections, increased residue, aspiration, pneumonia, and even death (Abrams et al., 2023).

Standardized Swallowing Protocols

The Yale Swallow Protocol (YSP), also called the 3 oz water test, is a screening tool used to identify aspiration risk. After a brief cognitive screen and oral mechanism exam, the patient drinks 3 ounces of water from a cup or straw with sequential swallows. The patient passes if they drink uninterrupted without signs of aspiration (i.e. coughing or choking).

The SLP provides the instruction, “Drink this entire cup slow and steady, but without stopping.”

According to a study involving 240 patients with dysphagia in post-acute care, the YSP has a sensitivity of about 95% and specificity of about 67% (Ward et al., 2020). Marvin and colleagues (2025) found that sensitivity and specificity are much lower for patients who were recently extubated, so it may not be as accurate in this population.

The Test of Mastication and Swallowing Solids (TOMASS) (PDF) evaluates the oral preparatory and oral phases of swallowing for regular solids using saltine crackers.

The SLP provides the instruction, “Eat this as quickly as is comfortably possible, and when you have finished, say your name out loud.”

The SLP collects data points, such as the number of bites per cracker, the number of mastication cycles, the number of swallows per cracker, and the total time to eat the whole cracker, over two trials. Normative data is available here.

CSE Master Guide Part 4:

Oral Bolus Trials

Part 4 of the CSE Master Guide takes you through liquid and solid bolus trials.

It includes the Yale Swallow Protocol (3-ounce water test) and the TOMASS (Test of Mastication and Swallowing Solids) right on the forms.

The final page helps you determine the next steps with documentation examples.

Sign up today to get your copy of the CSE Master Guide and try the digital treatments inside the Virtual Rehab Center.

Putting it All Together

Now you have all this information, but what do you do with it? Can you confidently suggest an oral diet? What are the risks, and what is the patient’s risk tolerance? Does the patient require an instrumental exam before eating or to inform therapy? If only this decision-making process were black and white. Unfortunately, it’s not —but that’s why we need to become experts and build our confidence in putting it all together for the best clinical outcomes.

The good news is that it doesn’t all fall on your shoulders. Diet recommendations and dysphagia care plans should always be collaborative between you, the patient and/or family, and the medical care team. This involves discussing your recommendations and reasoning, educating the patient about the risks, and making a decision together. Once you take the pressure off yourself and think of the CSE as a collaborative effort, you’ll find the process much less intimidating.

Cite this article: Shahid, S. (2025, October). What SLPs Need to Know: Clinical Swallow Evaluation. Tactus Therapy. https://tactustherapy.com/clinical-swallow-dysphagia-guide/