What SLPs Need to Know:

Executive Function & Aphasia

10 min read

When clinicians think about aphasia intervention, language naturally takes center stage. However, communication is more than just semantics and syntax; it’s a goal-driven task aimed at sharing information or connecting with others. Communication relies on high-level cognitive processes, or executive functions, to monitor and regulate progress toward the goal.

In an observational study, Olsson et al. (2019) found that 79% of participants with severe aphasia also had executive dysfunction. Given how common executive deficits are in this population and the potential impact on functional outcomes, quality of life, and health-care costs (Cumming et al., 2013), clinicians should proactively address executive function skills alongside language goals for patients with aphasia.

Dutta and colleagues (2024) outlined the executive skills needed for conversation:

- Inhibition– to suppress irrelevant thoughts and limit interruptions

- Working memory (updating)– to remember, manipulate, and update information

- Cognitive flexibility (shifting)– to adjust to the communication situation in the moment

- Attention– to maintain and shift attention between ideas

- Initiation and planning– to generate a topic, ideas, and convey information in an organized manner

- Reasoning and problem-solving– to work through communication breakdowns

- Self-awareness– to monitor errors

Inhibition, updating and shifting are often viewed as core functions, especially in the aphasia literature (Miyake & Friedman, 2012). These skills are frequently overlooked in people with aphasia, even though they are more likely to be impaired compared to individuals without language deficits (Andreou et al., 2023). For example, clinicians might notice patients perseverating on certain words (poor inhibition), losing track of what they’re saying mid-sentence (poor updating), or failing to switch modalities on their own when there’s a communication breakdown (poor shifting).

Learn more about executive functioning without aphasia here: “What SLPs Need to Know: Treating Executive Functioning in Speech Therapy”

Looking for Printable Handouts?

Unlock the Handout Vault

Dozens of high-quality, well-researched PDF handouts are available all in one place: The Tactus Virtual Rehab Center!

Patient education, home practice, clinical guides, visual supports, & a summary of this article for quick reference.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Access 50+ evidence-based treatments and 90+ handouts created specifically for adult medical speech-language pathologists.

Overlapping Brain Networks

Language and executive function both involve the left frontal cortex (Akkad et al., 2023), but functional imaging studies show that it’s more complex than that. High-level cognitive functions are supported by brain networks that span multiple lobes and both hemispheres, not just the frontal lobe (Meier et al., 2022). These networks often overlap with those responsible for language processing. A person with aphasia after a stroke may have weaker connections within these shared brain networks, in addition to focal damage to key language areas, like Broca’s area. This can lead to difficulties with executive function in addition to the language impairment.

Assessing Executive Function in Aphasia

Assessing executive functions can be challenging due to the task impurity problem. Since every complex task requires non-executive functions as well (like language or visuospatial processing), it’s nearly impossible to assess executive skills in isolation (Miyake et al., 2000).

Another complication involves the unity and diversity model, which states that executive functions are not entirely independent of one another, despite having unique features (Miyake & Friedman, 2012). Lastly, most assessments are not standardized explicitly on adults with aphasia, but they can still be used.

Useful assessment batteries for patients with aphasia include:

- The Butt Non-Verbal Reasoning Test (BNVR) examines problem-solving using pictures

- The Cognitive-Linguistic Quick Test Plus (CLQT+) offers an “aphasia administration” pathway

- The Raven’s Progressive Matrices tests abstract reasoning. There are three versions available, depending on the patient’s abilities: the Standard (SPM), Colored (CPM), and Advanced (APM) versions.

- The Test of Nonverbal Intelligence-4 (TONI-4) for abstract reasoning and problem-solving

Clinicians can also use individual tests with low language demands:

- Trail Making Test (PDF)

- Stroop Test (or Color Word Interference test)

- Tower of London Test

- Tower of Hanoi Test

- Kettle Test

Some researchers argue that it’s worthwhile to at least try a language-based cognitive test for someone with aphasia. It can offer valuable clinical insights you wouldn’t get from a non-verbal assessment. For example, Schumacher et al. (2022) used the Hayling Sentence Completion Test, a Verbal Fluency Test, and the Color Word Interference Test in their sample of 32 participants with aphasia. They caution to consider the patient’s tolerance, frustration, and time constraints when selecting a language-based assessment.

Ratings from significant others (informants) are usually a time-efficient way to gather information about a patient’s strengths and weaknesses. However, for individuals with severe aphasia, ratings may not accurately reflect executive function abilities (Olsson et al., 2020). In these cases, standardized assessments are more reliable than informant-based questionnaires.

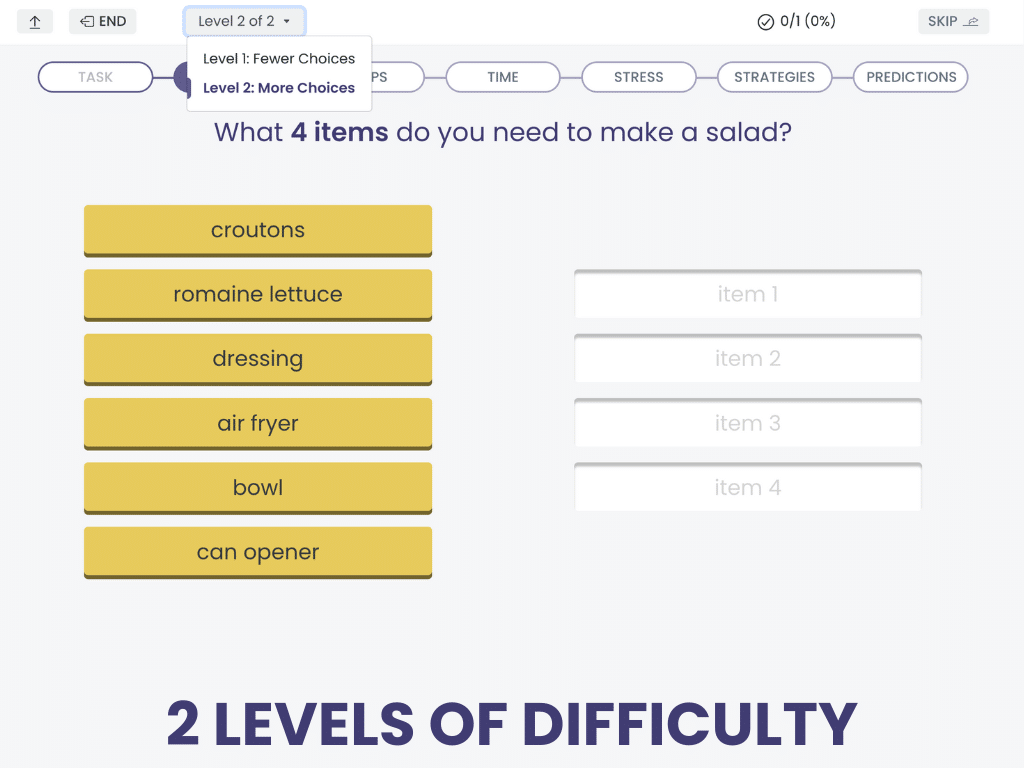

Non-Verbal Reasoning:

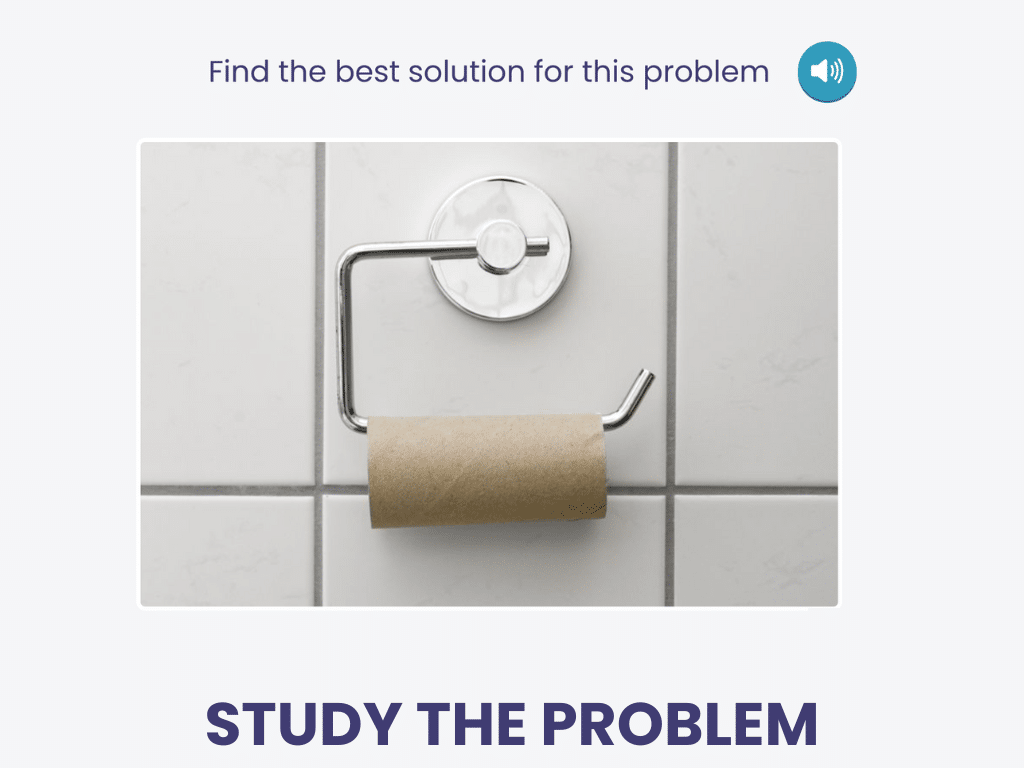

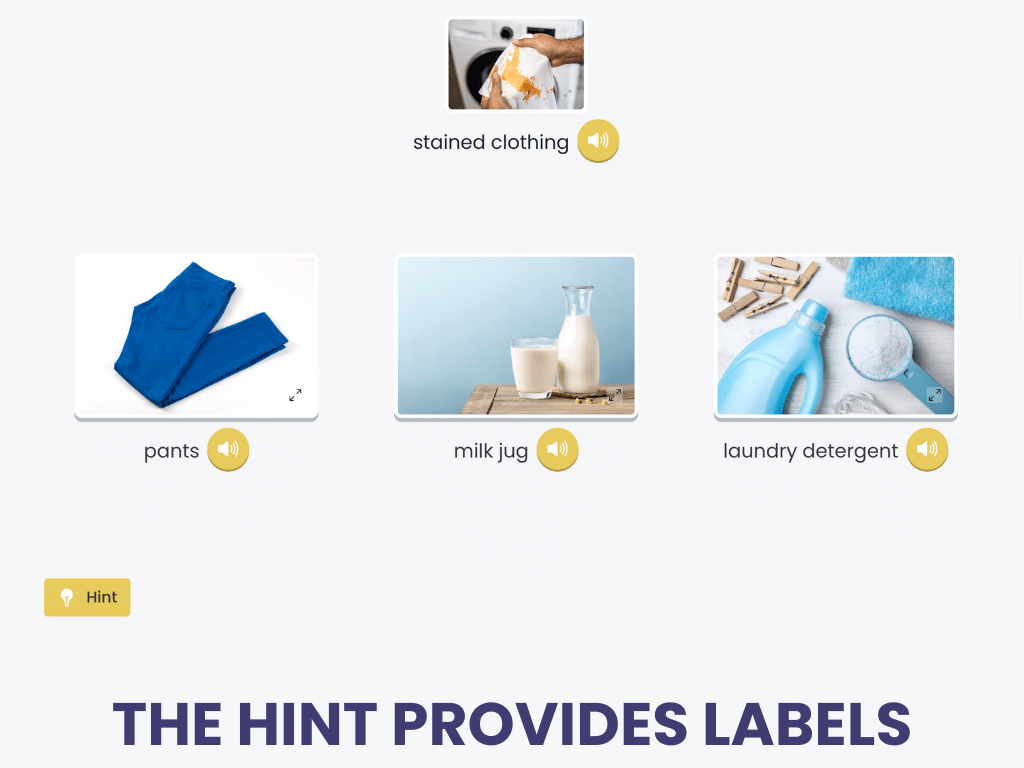

Solving Pictured Problems

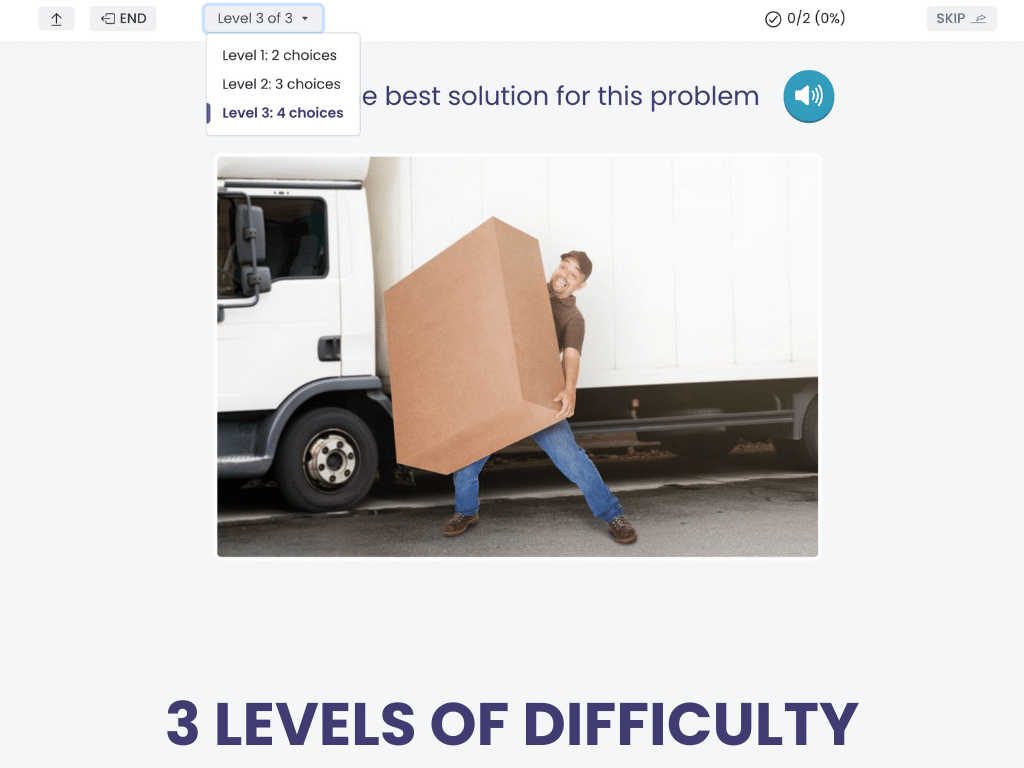

Solving Pictured Problems presents a photo of an everyday problem, then gives the patient 2, 3, or 4 choices of how to solve it.

The foils are carefully selected to be related to the problem or solution visually or semantically.

Solving Pictured Problems is a cognitive treatment in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

This treatment doesn’t require any language, but you can prompt the patient to explain their response, describe the problem, or name each proposed solution.

Cognitive Interventions Targeting Language

Interventions for executive function in individuals with aphasia aim to strengthen the cognitive processes that support goal-directed communication. In a systematic review, Culicetto et al. (2025) discussed how treating cognition can have a positive impact on language.

Treating Working Memory for Auditory Comprehension

Working memory plays a key role in auditory comprehension. It helps us hold onto information long enough to make sense of what we hear. For people with aphasia, this can be especially challenging.

Nikravesh et al. (2021) explored the benefits of working memory training for participants with mild-to-moderate aphasia. This working memory program consisted of forward and backward digit spans, paced auditory serial addition, and a categorization working memory task. After four weeks of training, participants demonstrated significant improvements in auditory comprehension. Repetition, naming, and speech fluency also improved.

N-back is a classic working memory task that can have a positive impact on auditory comprehension. In the N-back task, patients monitor a sequence of stimuli (e.g., letters, images, words) and indicate whether the current stimulus is the same as the one “n” steps earlier (e.g., one-back, two-back, etc.). Zakariás et al. (2018) delivered a modified N-back task to three people with chronic aphasia. Findings were very promising in terms of spoken sentence comprehension, with gains maintained at the six-week follow-up.

Technology makes it easy for patients to practice the N-back task, but there are plenty of other computer-based cognitive treatments that could impact language outcomes. For example, Liu and colleagues (2022) examined Computer-Assisted Executive Function Training (CAET), a program featuring interactive modules and adjustable difficulty levels that targets executive skills. Sixty-eight participants with aphasia and executive dysfunction were divided into two groups: one received traditional speech therapy plus CAET, while the other received speech therapy only. Participants in the CAET group showed greater gains in auditory comprehension, confirming that computer-based cognitive treatment can be a powerful tool for people with aphasia.

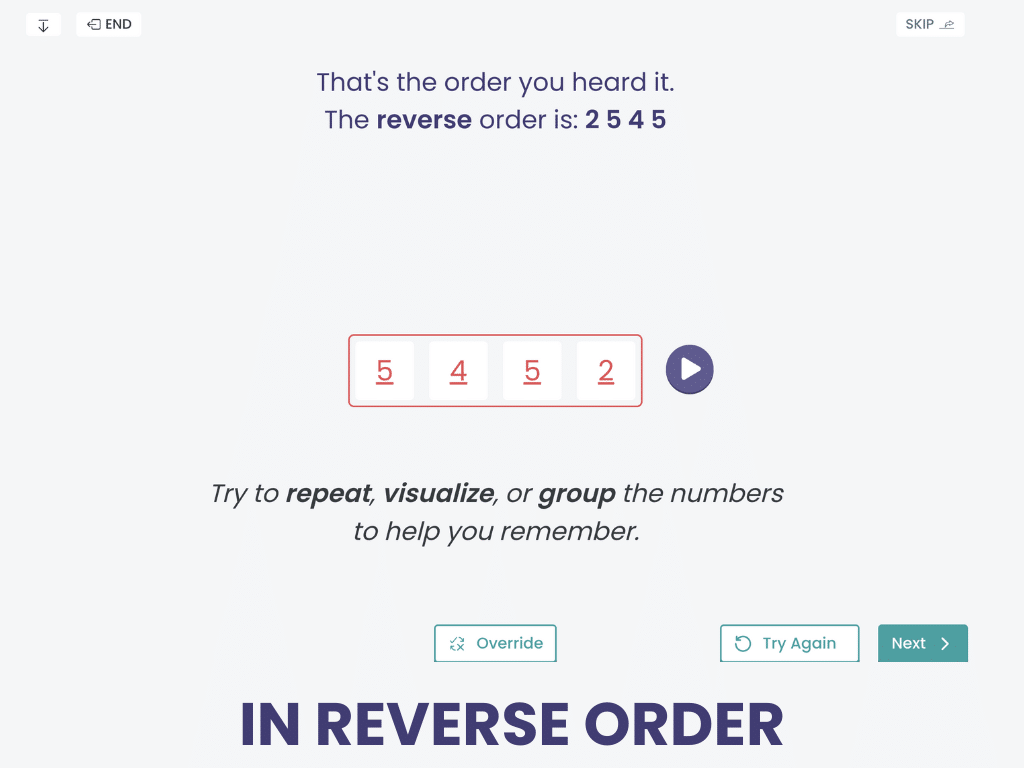

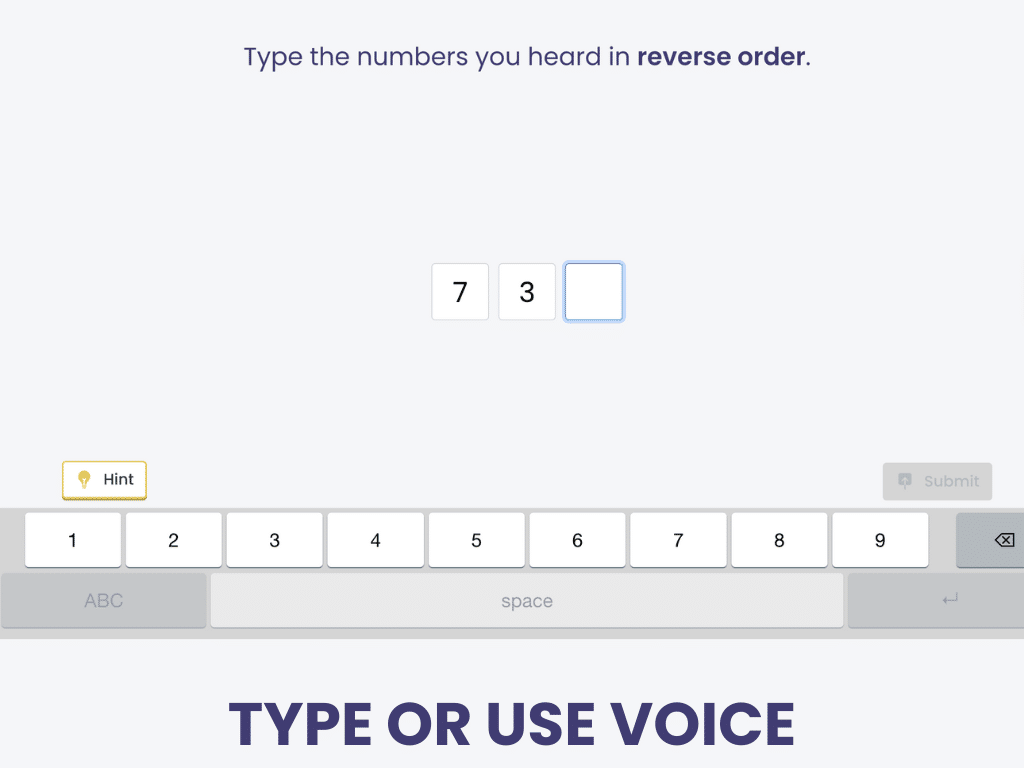

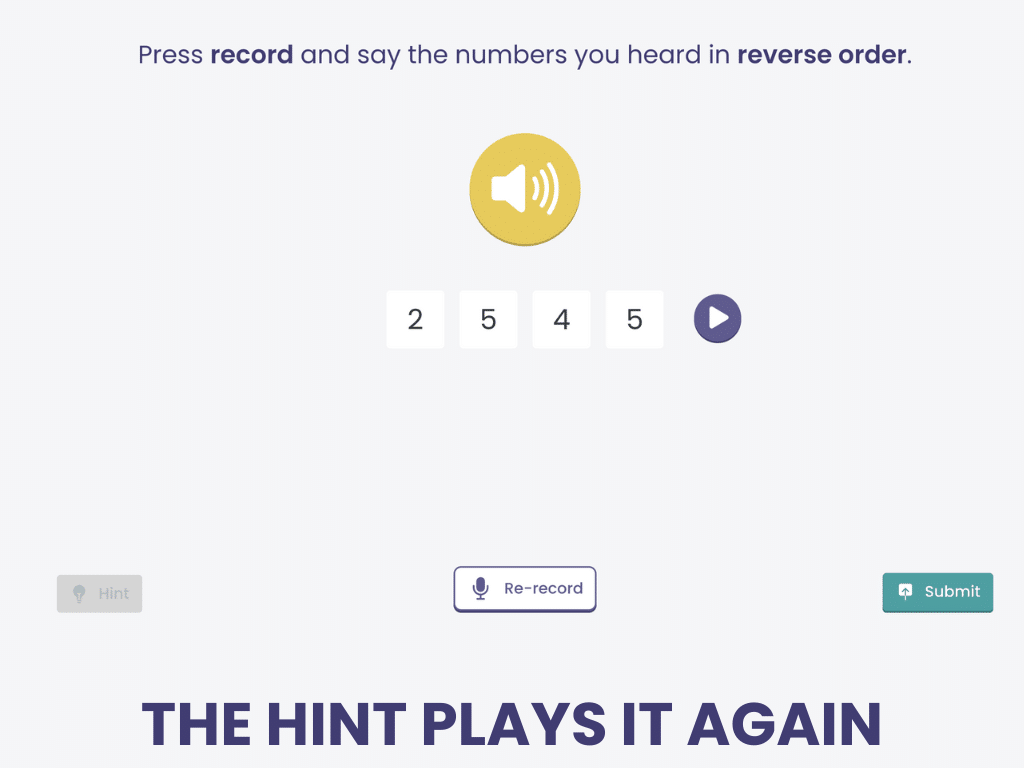

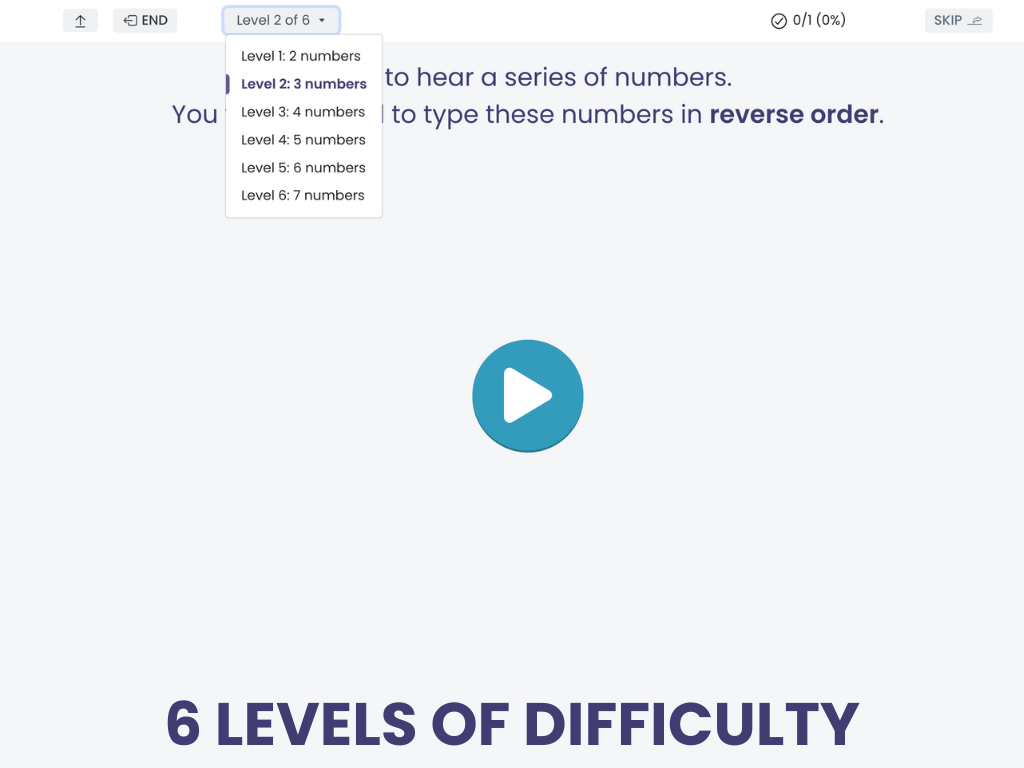

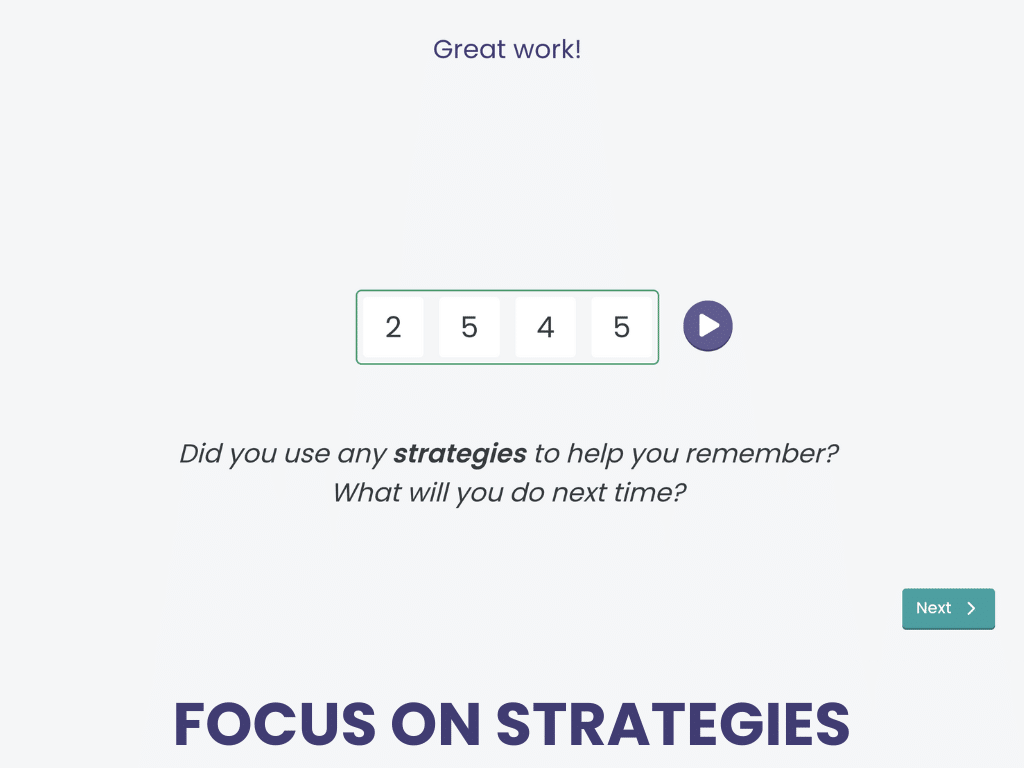

Backward Digit Span

Verbal Working Memory

Verbal Working Memory helps patients strengthen critical executive functioning skills by recalling digits in reverse order to what they hear.

Use speech recognition or choose typing the numbers to make it aphasia-friendly.

Verbal Working Memory is an evidence-based treatment in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Research shows that treatments like this can improve all areas of language, calling for it to be included in all aphasia rehab plans.

Treating Executive Function for Spoken Language

When we speak, we must plan what we want to say, hold ideas in mind, shift between topics, and monitor our message for clarity. For individuals with aphasia, difficulties with these executive skills can make spoken language even harder.

Bontemps and colleagues (2025) examined combining Semantic Feature Analysis (SFA), a well-established word-finding treatment, with executive function training in four individuals with aphasia. After 12 weeks of this combination therapy, naming skills and spoken discourse efficiency improved for all participants.

Another promising combination therapy is the Cognitive Flexibility in Aphasia Therapy (CFAT) program. CFAT involved spoken language tasks with an emphasis on flexible thinking, like:

- Alternating topics within a verbal fluency task

- Alternating between overt naming and circumlocution

- Alternating between confrontation naming and non-verbal expression

CFAT resulted in improvements across all language outcome measures and measures of verbal cognitive flexibility (Spitzer et al., 2021).

Treating Attention for Reading Comprehension

To understand written language, you need to sustain attention to the reading material, especially as the length increases. You also need working memory to hold onto new information as you read, while retrieving relevant information from your background knowledge (Lee & Sohlberg, 2012).

Through a handful of case studies, researchers have found that Direct Attention Training (DAT) improves reading comprehension through repetitive drills, possibly because of better allocation of attentional resources (Coelho, 2005; Sinotte & Coelho, 2007). More recently, Lee and Sohlberg (2013) incorporated metacognitive components (i.e., self-monitoring, self-ratings, and feedback) into DAT using the Attention Process Training-III program with four participants with chronic aphasia. Two of the four participants showed improved maze reading (a standardized curriculum-based measure) after eight weeks of treatment.

Learn more about how attention and aphasia are intertwined here: “What SLPs Need to Know: Attention and Aphasia.”

Adapted Metacognitive Strategy Instruction

Metacognitive strategy instruction (MSI) is a task-driven intervention that teaches patients to monitor and evaluate their performance. Unfortunately, most research on MSI has excluded people with aphasia because it requires in-depth communication between the therapist and patient.

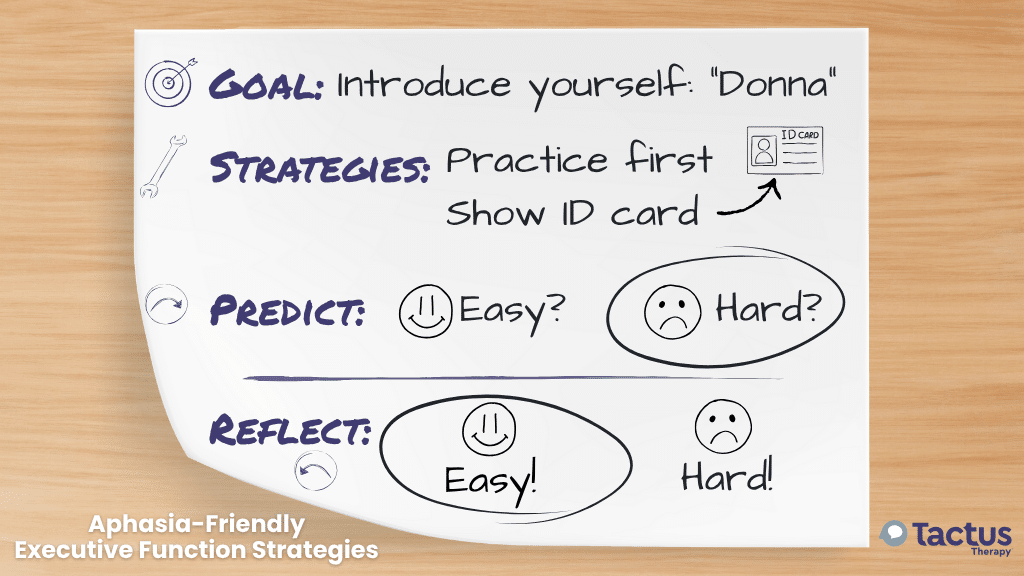

Kersey and colleagues (2021) employed supportive conversation techniques to adapt MSI for individuals with aphasia. They used whiteboards, letterboards, picture boards, an iPad, and verbal and visual cues to support understanding. Materials were also modified to be aphasia-friendly. Fifty percent of participants achieved mastery of the Goal-Plan-Do-Check strategy, a classic intervention for executive function.

Wadams & Mozeiko (2024) combined Multi-Modal Aphasia Therapy (M-MAT) with Goal Management Training (GMT) to create “M-Mat Meta” for two participants with Wernicke’s aphasia. M-MAT is a language treatment that encourages multi-modal communication in the context of group-based games. GMT is a metacognitive approach used to train planning, self-cuing, and self-regulation. Patients identify a goal, break it down into steps, recall the steps, and check the outcome. In this study, video feedback was used to promote self-awareness. After four weeks of training, both participants showed a decrease in aphasia severity, with improvements in naming, discourse, and response inhibition.

MSI should not be overlooked for people with aphasia because of the potential communication demands. Clinicians can adapt strategies and incorporate metacognitive elements, such as video feedback, into language interventions to improve awareness and error monitoring.

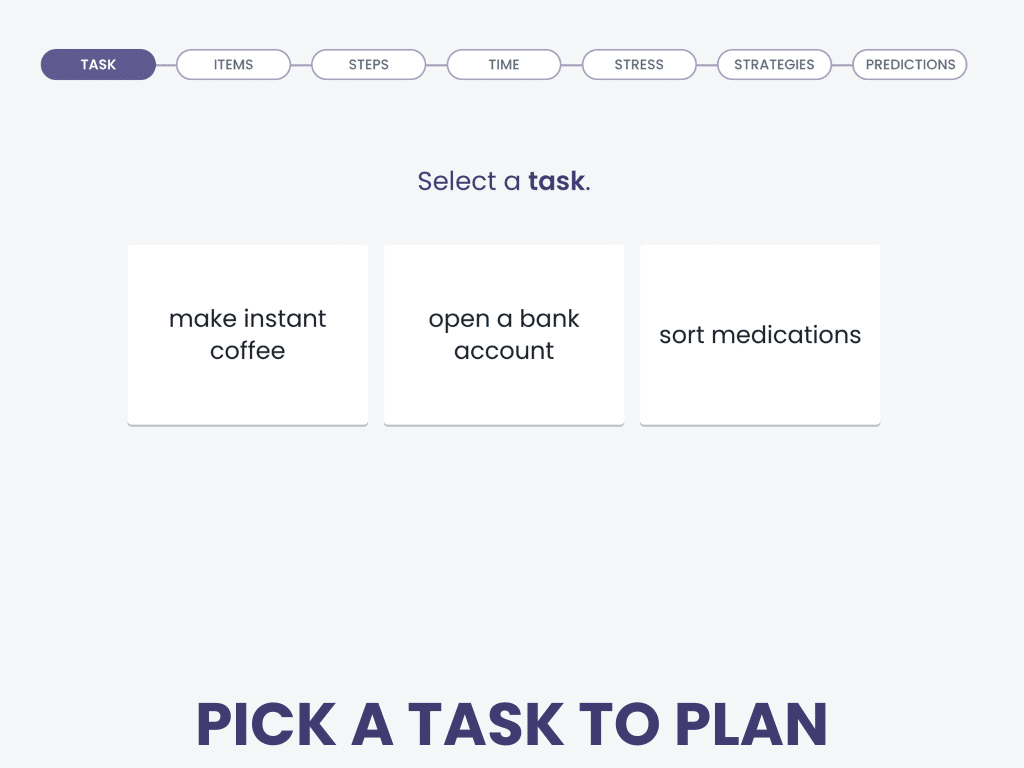

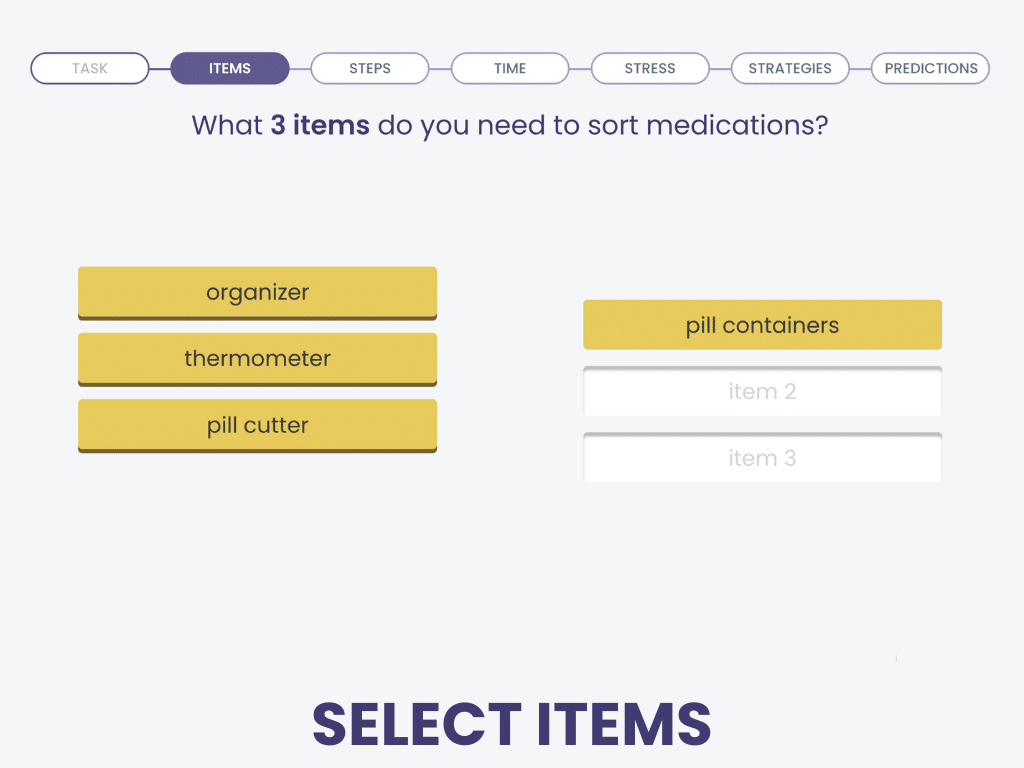

Aphasia-Friendly Executive Functioning

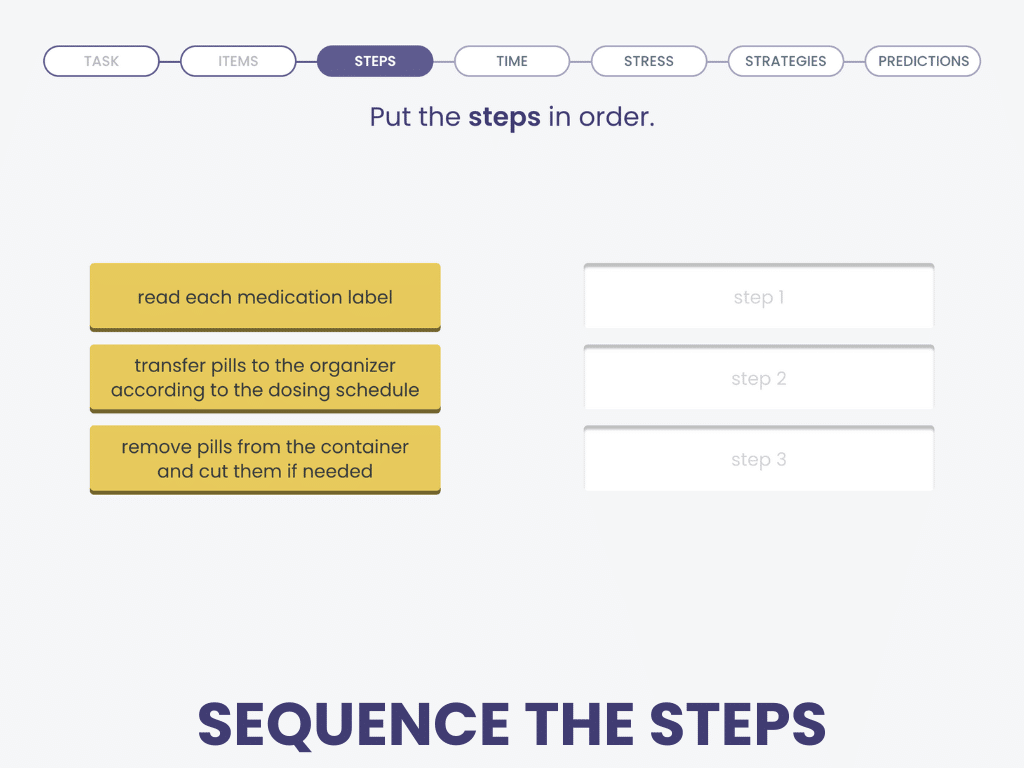

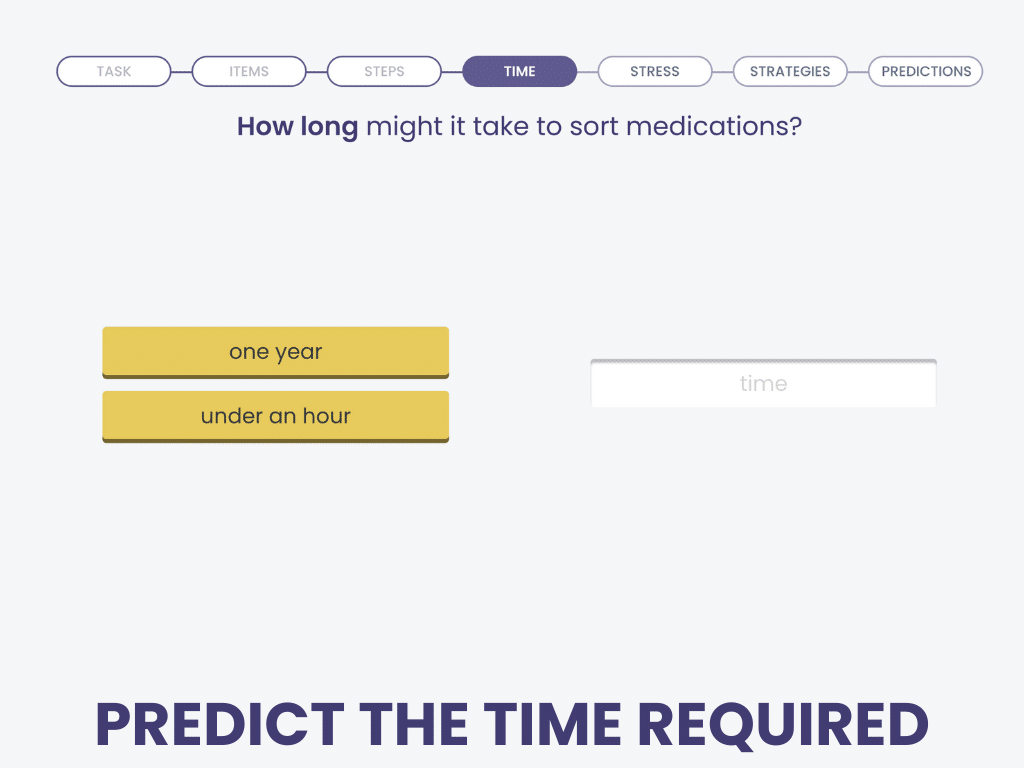

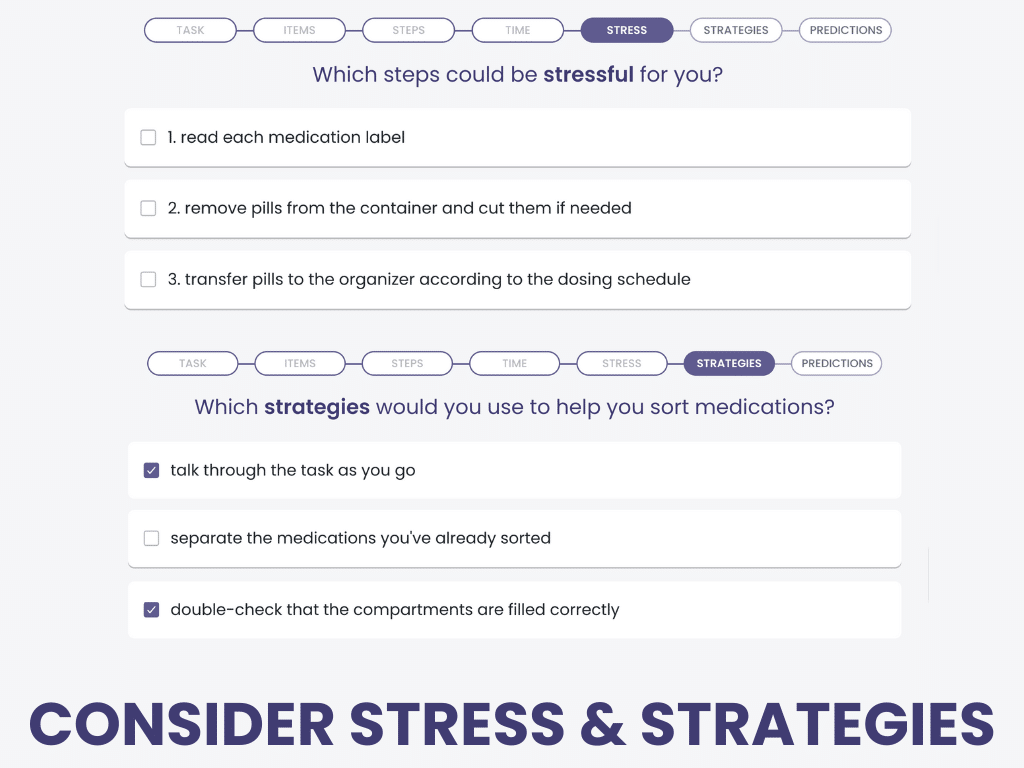

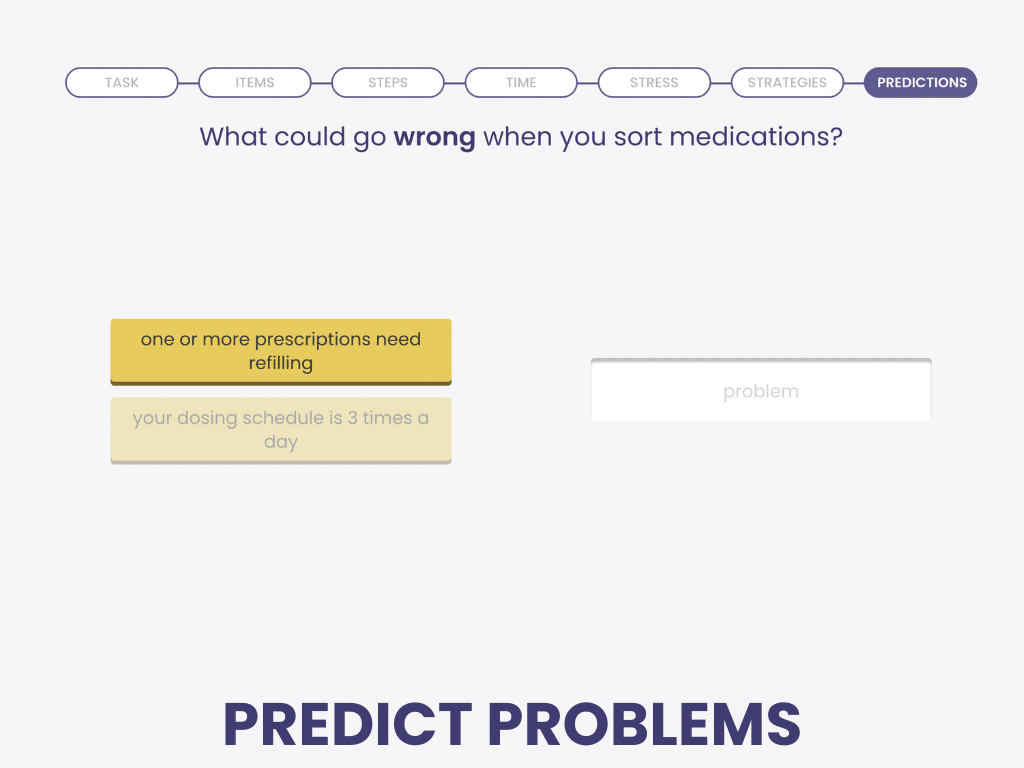

Planning Tasks

Planning Tasks helps patients practice the procedures of many executive function treatments without verbal or typed output.

Sequence the steps with drag-and-drop. Click on the items you need. No expressive language required!

Planning Tasks is an evidence-based treatment in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Give your patient repeated practice with functional scenarios before moving up to the personalized goal-management procedure of Planning Your Tasks.

Primary Progressive Aphasia and Executive Functioning

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a type of dementia that initially presents with deterioration of language skills. It was once believed that non-language cognitive skills remain intact in the early stages of PPA. However, recent research has shown that executive function problems can occur early on, across all PPA variants: non-fluent, semantic, and logopenic (Thomsen et al., 2024). For example, Chen et al. (2018) found that people with the semantic variant of PPA did worse than healthy controls on tasks measuring shifting and inhibition. Other studies have reported similar difficulties with inhibition in the non-fluent and logopenic types (Matias-Guiu et al., 2019; Gajardo-Vidal et al., 2024). Overall, executive function impairments tend to be more severe in the non-fluent and logopenic variants than in the semantic variant (Coemans et al., 2022).

AAC & Executive Function

Nicholas et al. (2011) found that participants with aphasia who had stronger executive function skills responded better to AAC (augmentative and alternative communication) training than those with impaired skills. This requires learning, a concept that’s closely tied to executive function.

Not only do you need executive function skills to learn to use AAC, but you also need them every time you use it to communicate. Per Nicholas & Connor (2016), patients must follow these steps to communicate using AAC:

- Create an internal message (initiation)

- Generate ideas (planning)

- Hold on to the ideas while accessing the device (attention, working memory)

- Search for a number, letter, picture, or message and choose one that matches the idea (attention, cognitive flexibility, inhibition, problem-solving)

- Shift to a new strategy if there isn’t a match (cognitive flexibility, problem-solving)

- Or repair an error (self-monitoring)

- Anticipate the conversation partner’s response (awareness for turn-taking)

Before introducing a new system, clinicians can administer the Multi-Modal Communication Screening Task for Persons with Aphasia (MCST-A) to help guide intervention. This tool helps identify which patients may need partner-supported communication and which are more likely to use AAC independently.

Final Thoughts on Executive Function and Aphasia

Executive function skills play a critical role in how people with aphasia communicate. These complex cognitive skills help with everything —from understanding conversations, to reading a book, to using word-finding strategies, to using AAC. As speech-language pathologists, it’s important to keep executive function in mind when assessing and planning treatment for our patients with aphasia.

Learning More about Attention and Aphasia

The sources we used for the article are linked where they are cited. If you want to learn more, this is an excellent reference to read:

Cite this article: Shahid, S. (2025, July). What SLPs Need to Know: Executive Function & Aphasia. Tactus Therapy. https://tactustherapy.com/executive-function-and-aphasia-speech-therapy/