What SLPs Need to Know:

Dysphagia Exercises

12 min read

For patients with dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing, mealtimes can quickly become a source of risk, stress, and frustration. An evidence-based dysphagia exercise program can make a big difference in functional outcomes, allowing patients to eat and drink with greater safety and less discomfort.

Dysphagia exercises are targeted movements that improve the strength, coordination, and timing of the muscles used in swallowing. Unlike compensatory strategies that aim to make swallowing safer in the moment, these exercises focus on long-term improvement by addressing specific physiological impairments.

Not all patients with dysphagia are appropriate for an exercise program. It’s important to consider a patient’s cognitive and physical limitations, such as surgical precautions or respiratory status. Consult with the healthcare team to discuss possible contraindications. When designing a dysphagia treatment plan, exercises should be selected for the patient’s specific impairments based on the findings of an instrumental assessment (FEES or VFSS).

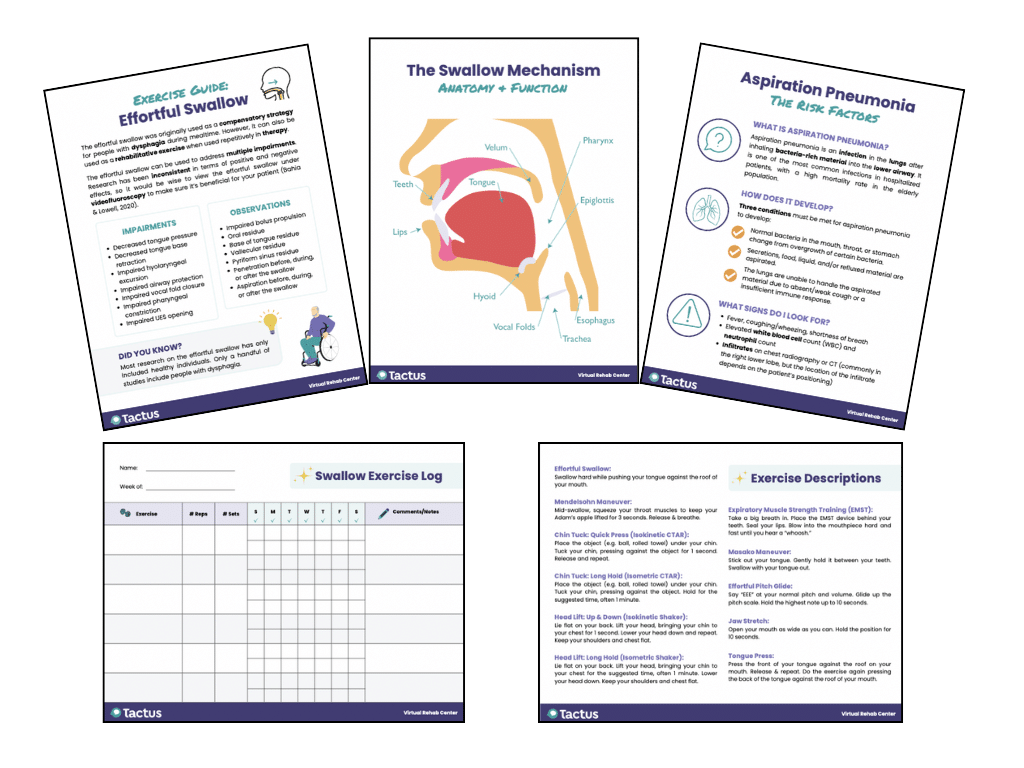

Looking for Printable Handouts?

Unlock the Handout Vault

Dozens of high-quality, well-researched PDF handouts are available all in one place: The Tactus Virtual Rehab Center!

Patient education, home practice, clinical guides, visual supports, & more.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Access 50+ evidence-based treatments and 90+ handouts created specifically for adult medical speech-language pathologists.

Go-To Dysphagia Exercises

The growing body of research evidence on dysphagia exercises can be overwhelming. Variations in patient populations, study designs, dosage, and outcome measures make it hard to compare studies. Here is a focused look at some of the more commonly used approaches, along with a few studies that stood out for their clinical value.

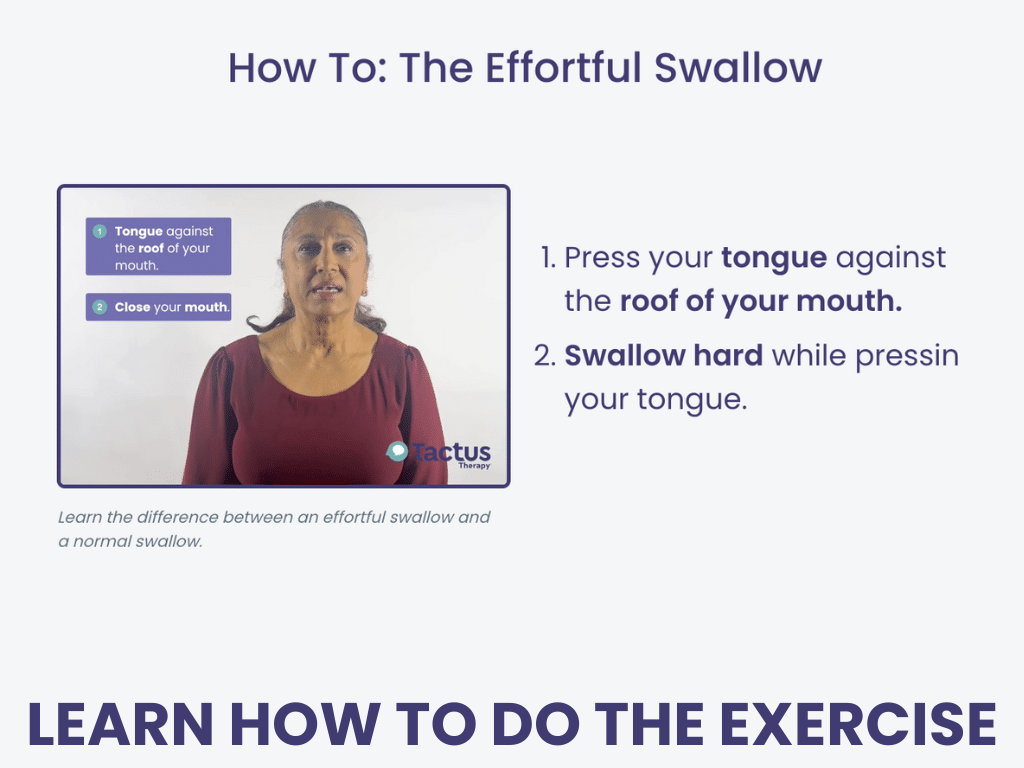

Effortful Swallow

The effortful swallow is a simple and popular rehabilitative exercise, as well as a compensatory strategy. It targets multiple aspects of the swallow simultaneously.

Patients are instructed to “Swallow hard while pushing your tongue against the roof of your mouth” to emphasize tongue-to-palate contact for better outcomes (Huckabee & Steele, 2006).

Patients need to alter their typical swallow during this exercise to see positive physiological change, which isn’t always easy. Biofeedback tools like surface electromyography (sEMG) can help by providing visual cues about muscle activity, giving patients real-time insight into their swallow effort. Archer and colleagues (2020) found that using biofeedback during the effortful swallow led to increased muscle activation. Plus, participants reported that the exercise felt significantly easier with this tool.

According to a systematic review by Bahia & Lowell (2020), physiological improvements related to the effortful swallow can include:

- Increased tongue-to-palate pressure and duration

- Increased base of tongue pressure and duration

- Increased hyolaryngeal movement

- Prolonged laryngeal closure

- Increased pharyngeal contraction with a positive impact on epiglottic inversion and duration of inversion

- Increased upper esophageal sphincter (UES) pressure and duration of opening

- Increased esophageal pressure, especially in the mid and distal regions

The research literature is inconsistent, and at times conflicting, with the physiological changes resulting from the effortful swallow. Much of the research on the effortful swallow uses healthy adults as subjects, not people with dysphagia. This is why clinicians should view the effortful swallow on VFSS to determine if it will reduce penetration, aspiration, and/or pharyngeal residue for the individual patient.

Technology for Tracking Exercise:

Effortful Swallow

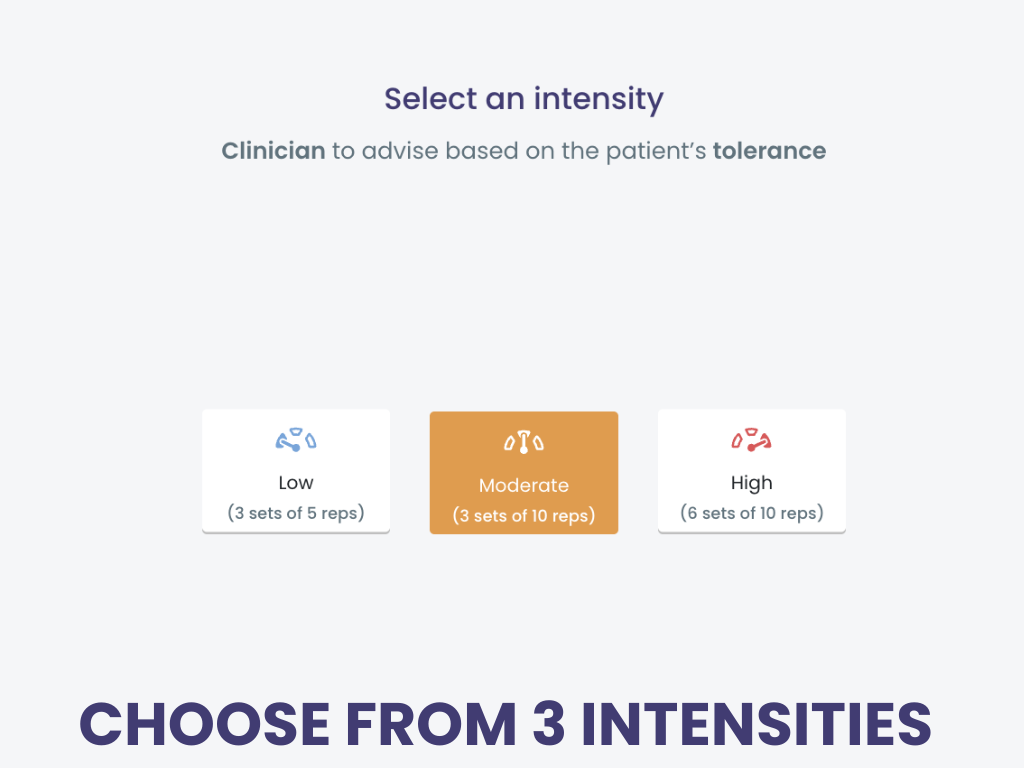

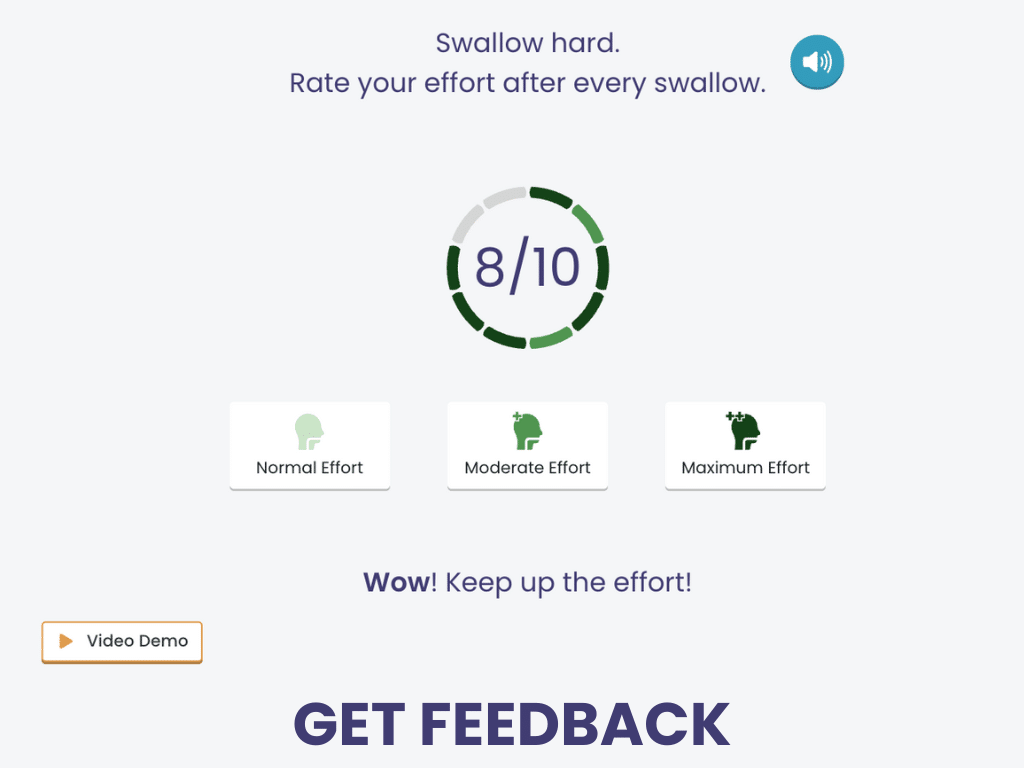

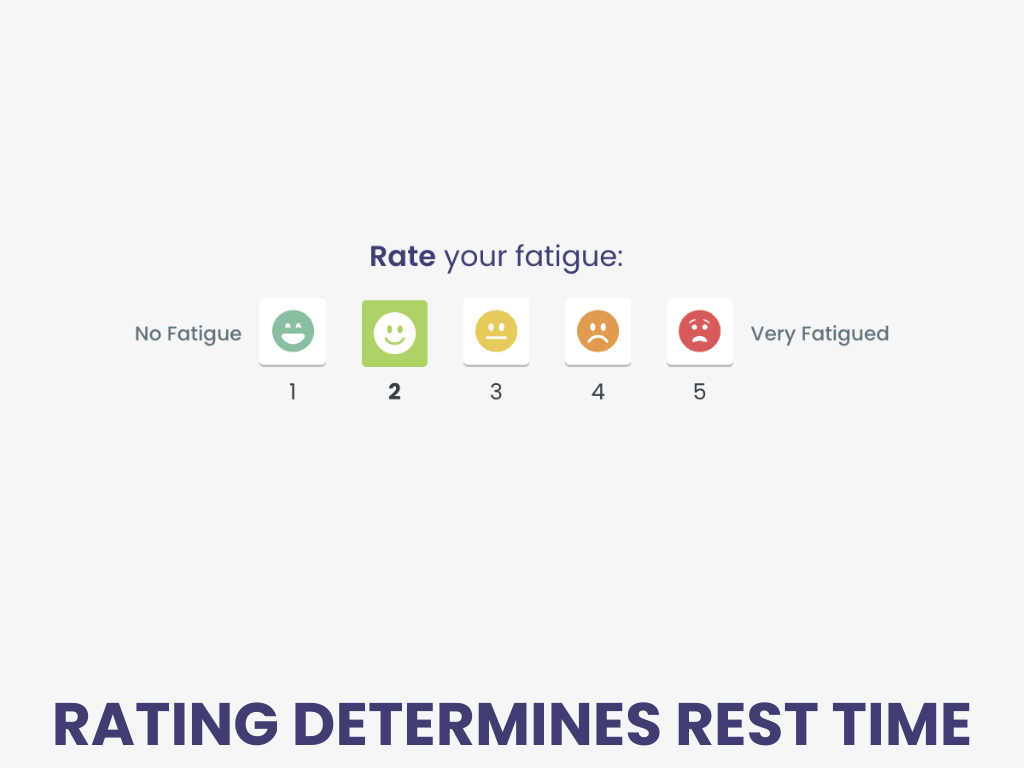

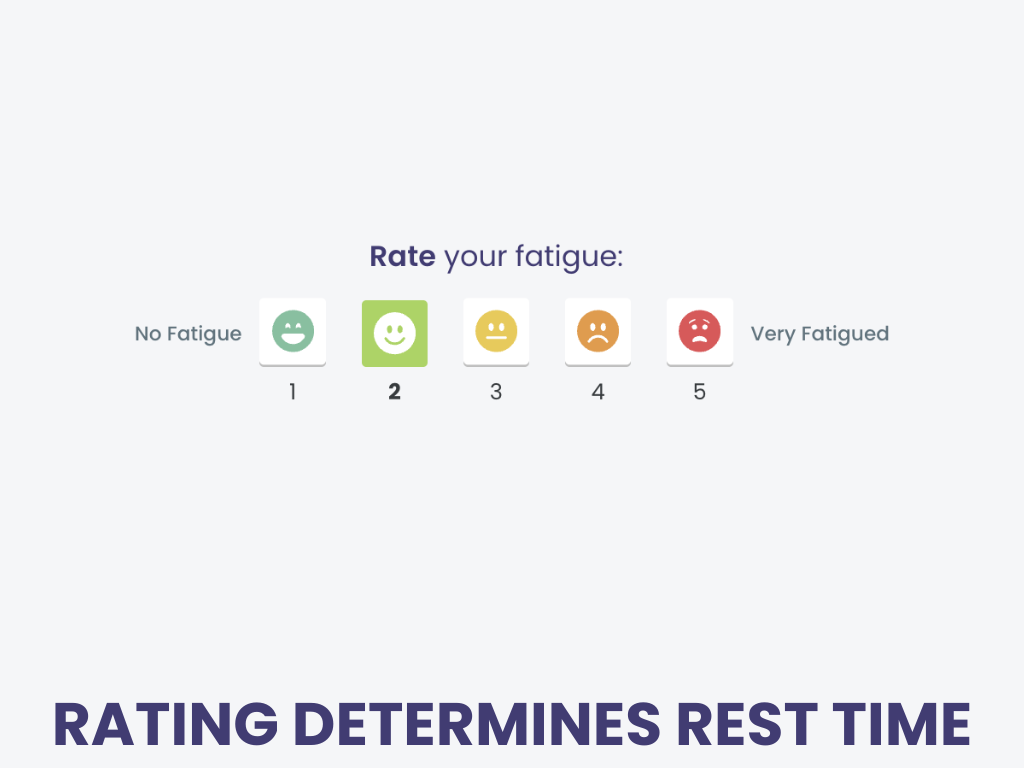

Effortful Swallow guides patients through their sets of repeated exercises with feedback based on self-ratings.

Patients indicate the perceived effort of each swallow, advancing the counter. A video model is available for review.

Effortful Swallow is a dysphagia treatment in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

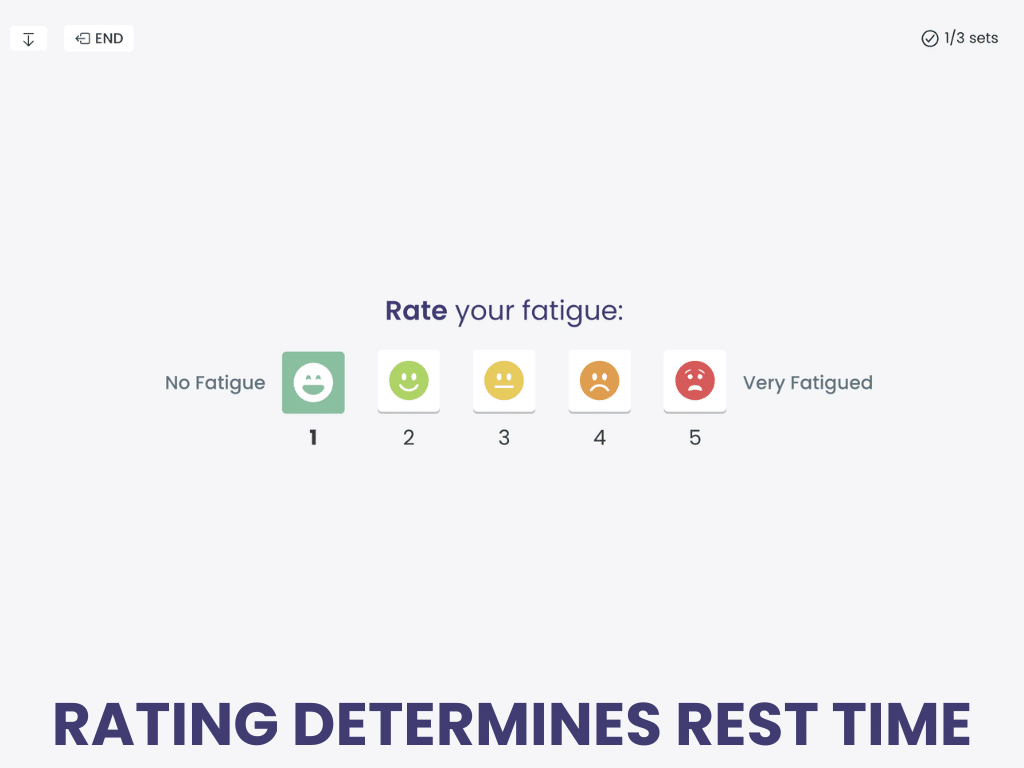

Use technology to guide and track swallowing exercises, provide feedback, and even write the SOAP note! Home practice is free for your patients to speed recovery.

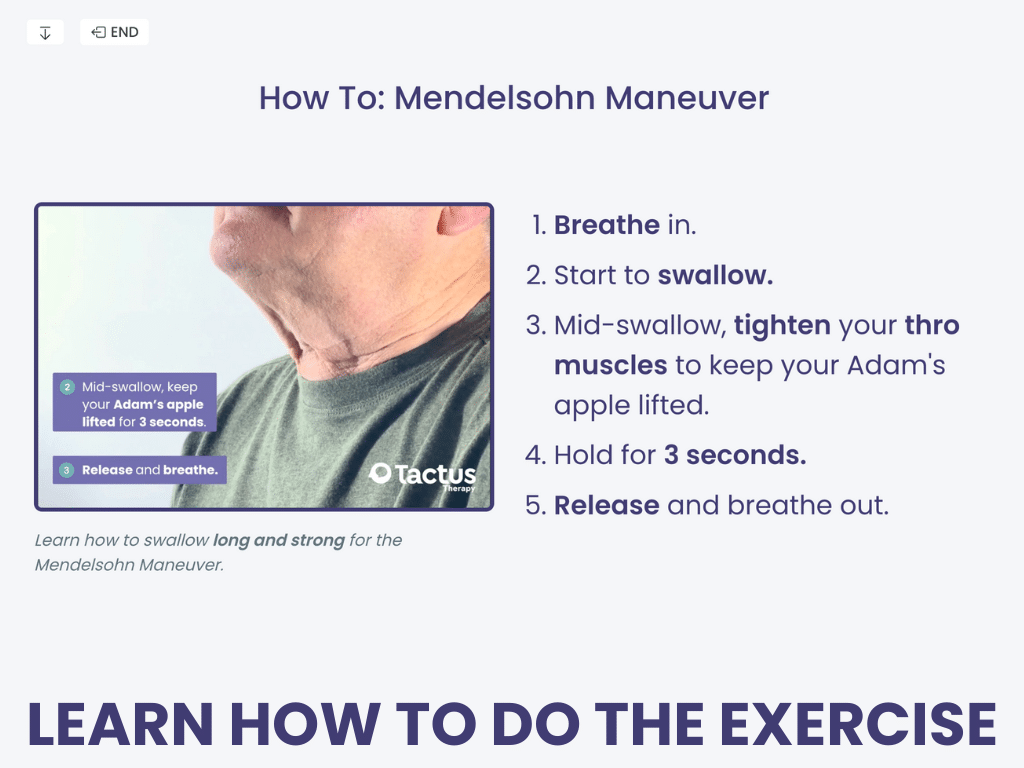

Mendelsohn Maneuver

The Mendelsohn maneuver is another classic swallowing exercise and strategy designed to improve hyolaryngeal movement, pharyngeal pressure, UES opening, and esophageal pressure (Khemlani et al., 2024).

Patients are instructed to “swallow long and strong” by squeezing their throat muscles at the peak of their swallow for about 3-4 seconds, then release.

This maneuver is a bit more complex than other exercises, requiring good comprehension and motor control, so not every patient will be the right fit. Teplansky & Jones (2022) found that the Mendelsohn maneuver had the largest effect size in terms of inconsistent performance compared to other swallow exercises. When performed effectively, ideally with biofeedback, it can be a powerful tool in dysphagia rehab.

McCullough & Kim (2013) studied the effects of the Mendelsohn maneuver on participants post-stroke with dysphagia. Participants completed 30-40 repetitions per session using sEMG for biofeedback. The duration of hyoid maximum elevation showed statistically significant gains. The maximum anterior excursion of the hyoid and the width of the UES opening also improved.

Swallow Long & Strong:

Mendelsohn Maneuver

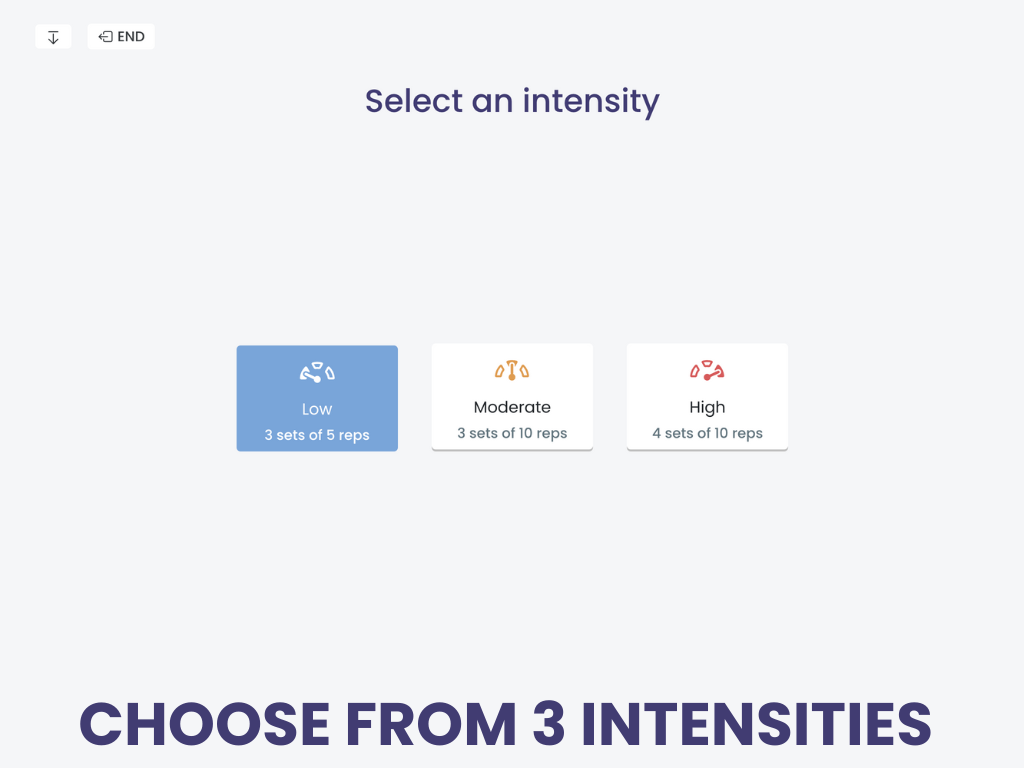

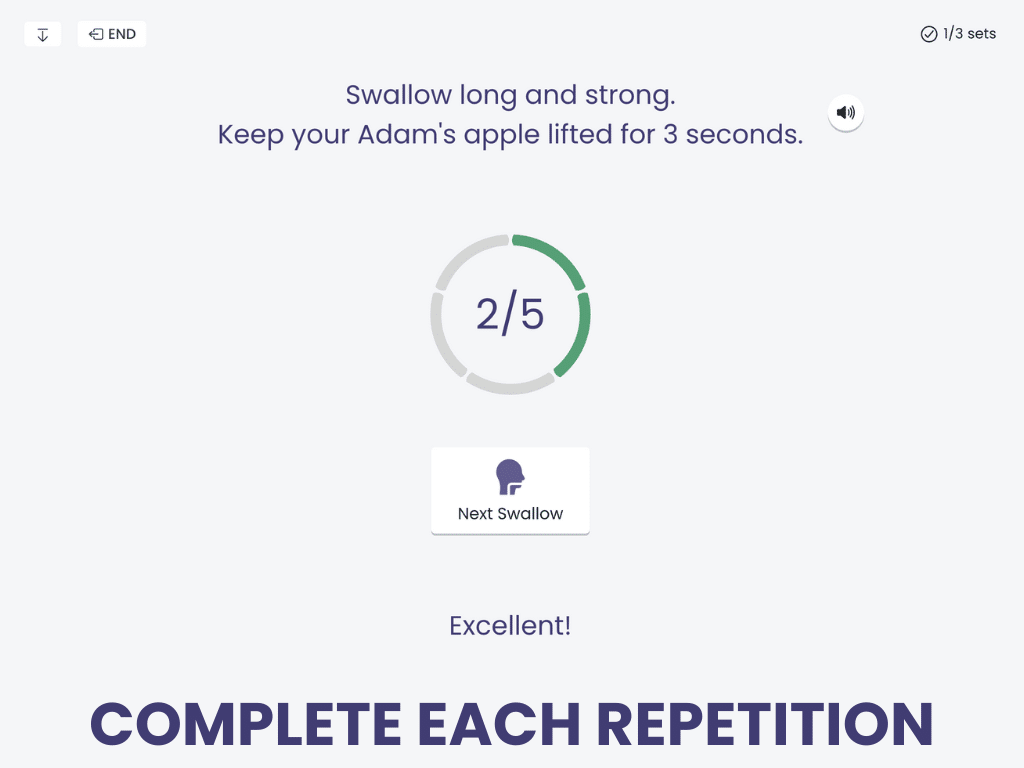

Mendelsohn Maneuver is an evidence-based dysphagia treatment in the Virtual Rehab Center to strengthen the muscles of swallowing.

Patients are guided through long holds of laryngeal elevation, advancing a counter until they reach their repetition target.

Mendelsohn Maneuver is one of several treatments in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

We know that it can be hard for patients to track home practice of swallowing exercises. That’s why we make it free and easy.

Chin Tuck Against Resistance (CTAR)

The Chin Tuck Against Resistance (CTAR) exercise targets the suprahyoid muscles. The suprahyoid complex is responsible for the movement of the larynx, hyoid bone, epiglottis, and UES opening to allow the bolus to flow into the esophagus (Liu et al., 2023). It’s performed in a seated position using a small ball or resistance device.

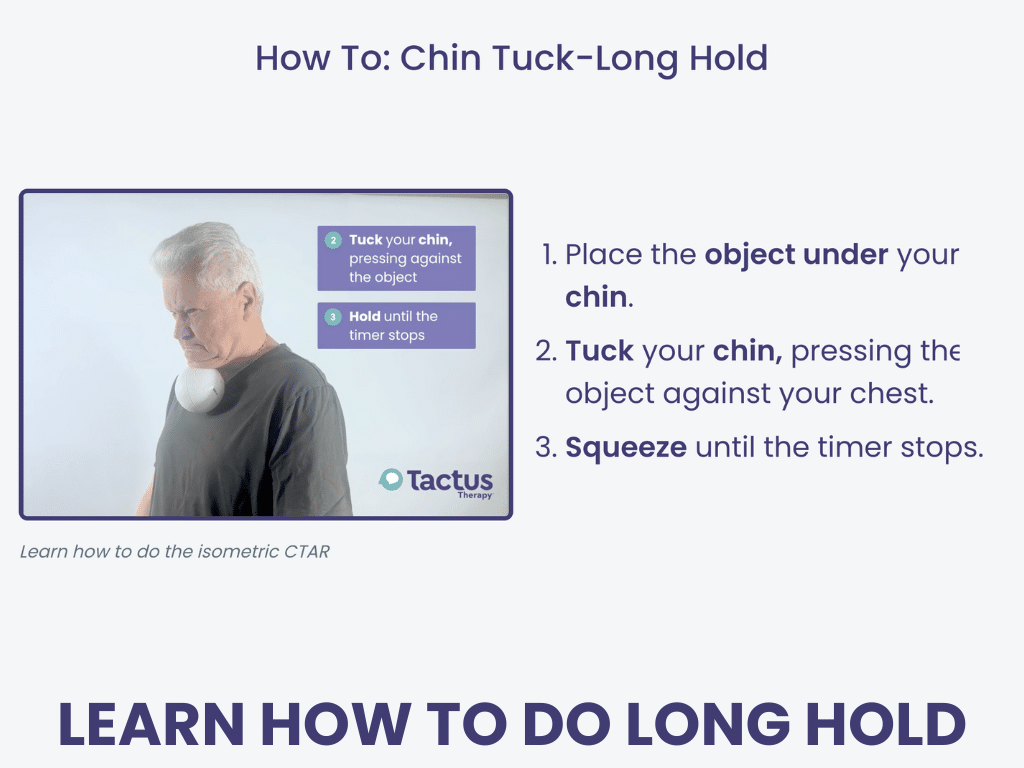

For the isometric CTAR exercise, the patient tucks their chin toward their chest while compressing the resistance ball. They hold this position for 10-60 seconds each set.

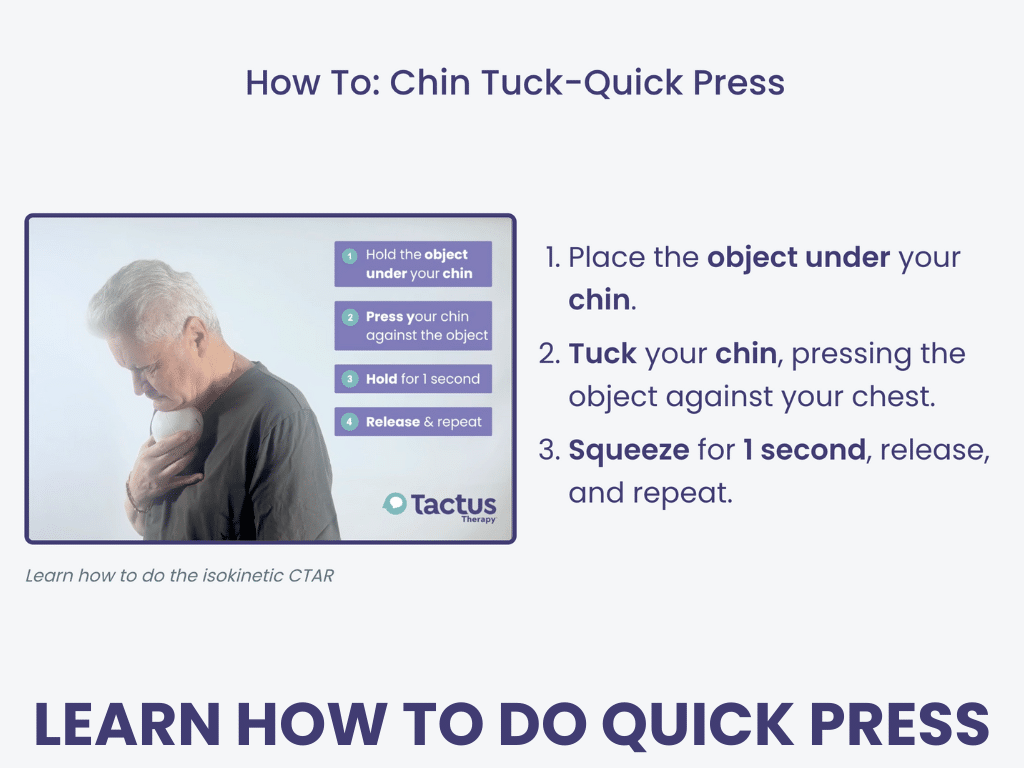

For the isokinetic CTAR exercise, the patient tucks their chin toward their chest, briefly squeezing the resistance ball, then lifts their chin back up. They complete about 30 consecutive squeezes per set.

Commercially available CTAR balls are approximately 12 cm in diameter, though clinicians often use alternative items that are readily available, such as a rolled towel or roll of toilet paper. CTAR has quickly become a popular choice in dysphagia exercise programs, although some academics question the benefit of targeting neck flexion for dysphagia.

According to a systematic review, subjects who performed the CTAR had lower Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) scores, improved oral intake ability, and an increased rate of nasogastric tube removal compared to control groups (Liu et al., 2023). When directly compared to the traditional Shaker exercise, the CTAR group showed greater improvement in swallow safety.

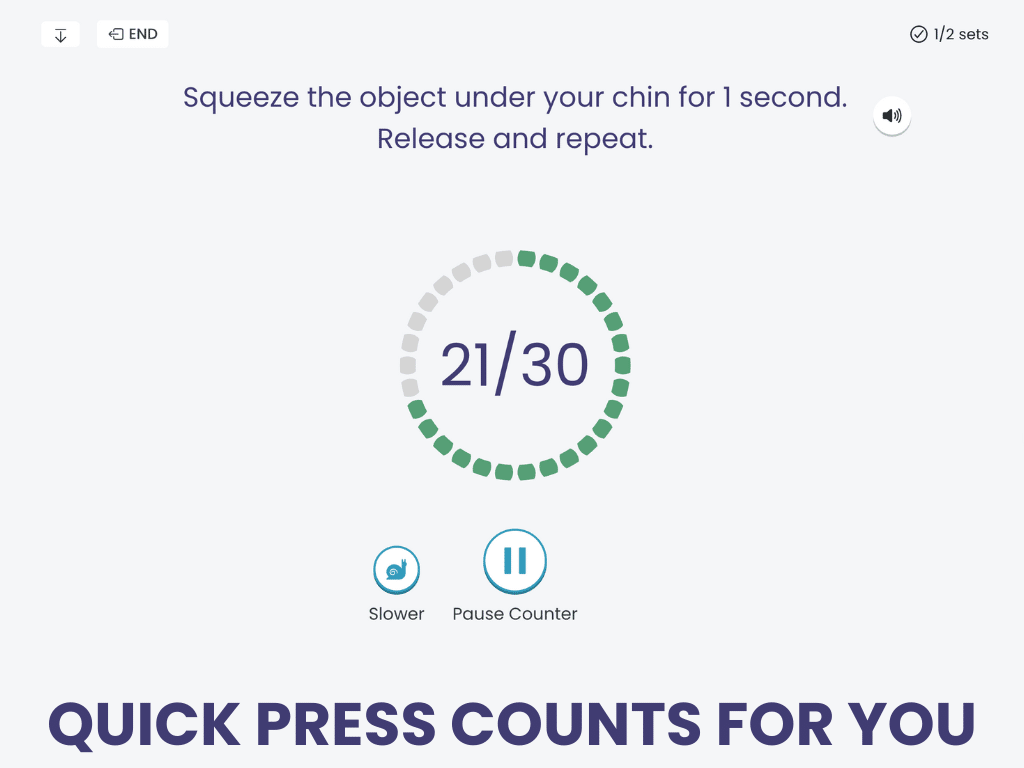

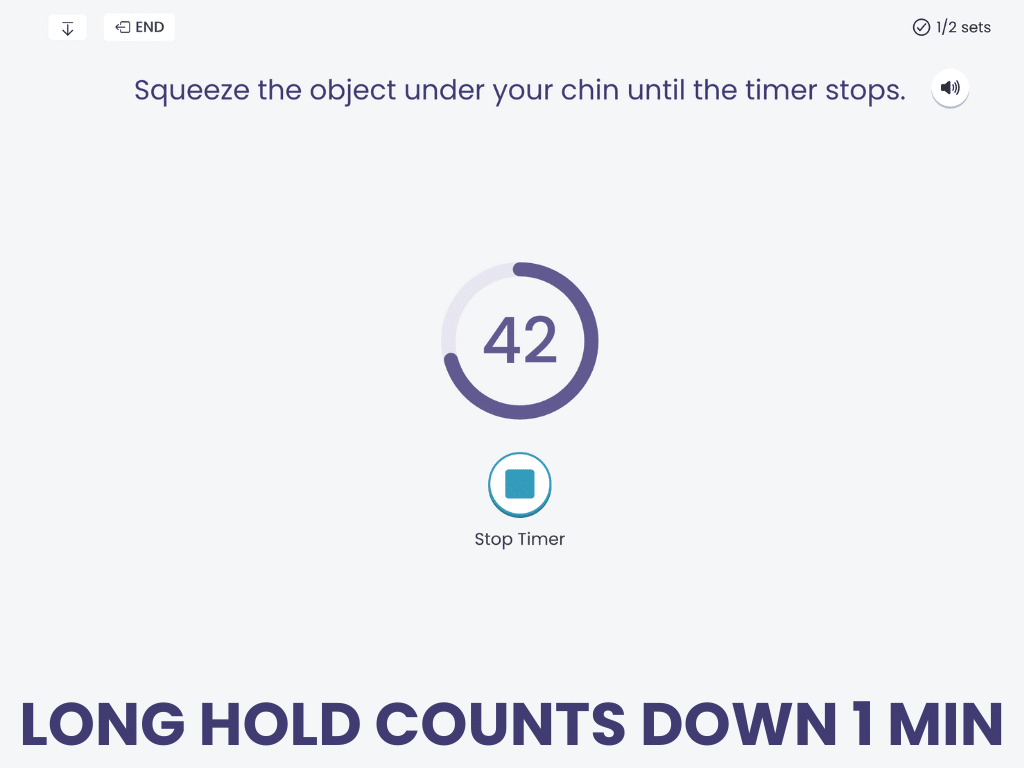

Two CTAR Treatments:

Chin Tuck: Long Hold & Quick Press

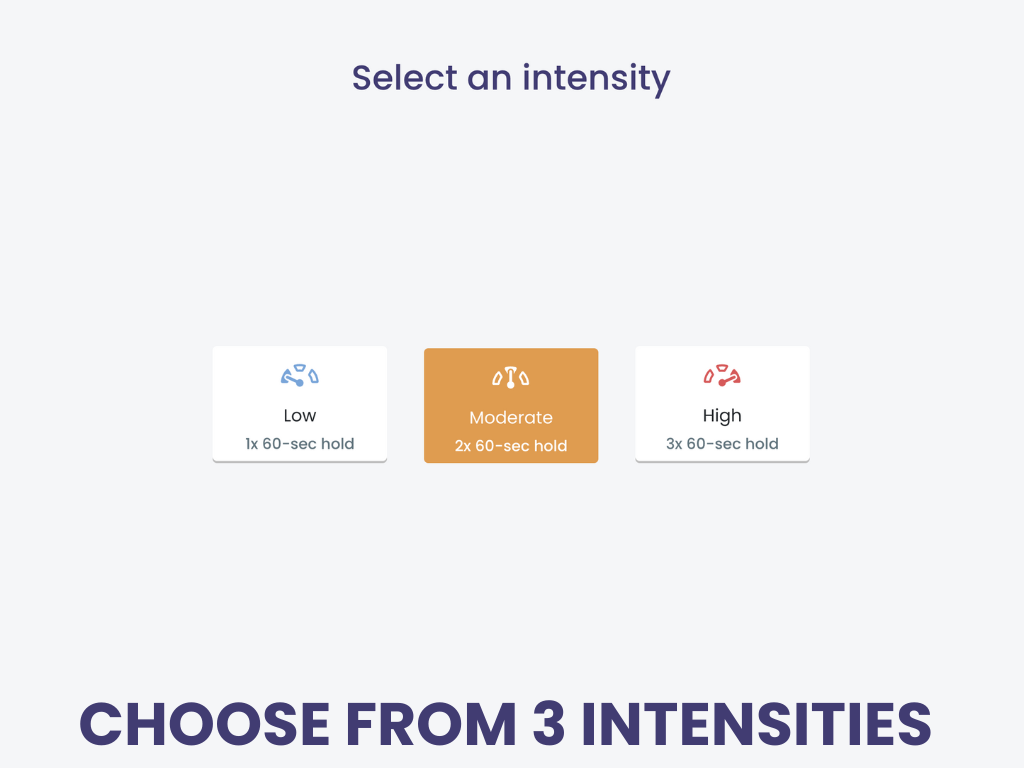

Chin Tuck: Long Hold & Chin Tuck: Quick Press are 2 treatments in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center to strengthen the muscles of swallowing.

Long Hold guides patients through a 1-minute compression of a ball against the chest for isometric CTAR, while Quick Press counts out thirty 1-second compressions for isokinetic CTAR.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Home practice for patients is always free and can be done on any computer or device with a web browser. SOAP notes are delivered right to your clinician portal.

Shaker Exercise

The Shaker exercise, also known as the head-lift exercise, predated the CTAR. It also targets the suprahyoid muscle complex that elevates the larynx and opens the UES during swallowing. It’s most commonly prescribed for patients who show signs of reduced UES opening or pharyngeal residue, especially in the pyriform sinuses.

For the isometric Shaker exercise, the patient lies down and lifts their head, looking toward their toes, holding this position for 1 minute.

For the isokinetic Shaker exercise, the patient lies down and lifts their head up and down for multiple consecutive repetitions.

The Shaker can be physically demanding. Patients must complete this exercise in the supine position (on their back), so consider a patient’s neck mobility and strength before assigning it. If this isn’t feasible for a particular patient, the CTAR exercise may be more appropriate.

Overall, the evidence for the Shaker exercise has been mixed. Logemann et al. (2009) and Park et al. (2017) both reported positive results for participants with dysphagia, such as reduced post-swallow aspiration. However, Tuomi and colleagues (2022) did not find consistent swallowing improvement following a Shaker exercise program involving subjects with head and neck cancer.

Expiratory Muscle Strength Training (EMST)

Expiratory Muscle Strength Training (EMST) is a respiratory-based exercise in which patients use a pressure threshold device (e.g. EMST150 or EMST75 Lite) to give the submental muscles a workout. EMST can improve hyolaryngeal movement, reduce penetration and aspiration during and after the swallow, improve airway clearance, and increase UES relaxation (Richardson, 2024). EMST has shown promise in populations like Parkinson’s disease, stroke, COPD, and ALS—but like any intervention, it’s not one-size-fits-all. With the right candidates and proper instruction, EMST can be a valuable part of a dysphagia exercise program.

Before starting EMST, the clinician must determine the patient’s maximum expiratory pressure (MEP). This is the highest generated pressure during forceful expiration against a blocked airway. MEP is measured in centimeters of water (cm H20). Here’s how to calculate the MEP using the EMST150 or EMST75 Lite:

- Set the device to the lowest setting by rotating the cap counterclockwise.

- Put nose clips on to prevent air leakage. (optional)

- Take a breath in. Put the device in your mouth.

- Blow hard and fast into the device.

- If this is too easy, turn the cap ¼ turn clockwise and repeat steps 2-3 until you can’t blow through the device. The number displayed is your MEP.

Training typically starts at 75% of the patient’s MEP (about ¼ turn back from the MEP), but you might start as low as 50% for certain patient populations, like ALS (Richardson, 2024).

EMST follows the rule of fives: 5 sets of 5 exhalations per session, 5 times per week, over a 5-week period (Mancopes et al., 2020). After each week, turn the cap ¼ turn clockwise to increase the resistance. If it becomes too easy or too hard, adjust the resistance accordingly. After the patient completes 5 weeks of training, they can begin the maintenance program: 5 sets of 5 breaths, 3 times per week.

Tongue Stretching & Strengthening

The tongue plays a critical role in safe and efficient swallowing. It is used in mastication, bolus formation, and bolus propulsion into the pharynx. When lingual range of motion or strength is reduced, patients may present with poor bolus control, premature spillage, and oropharyngeal residue. Tongue stretching and resistance exercises target these deficits. Overall, there is positive evidence that these exercises improve tongue pressure (Smaoui et al., 2019).

In a study by Hwang et al. (2019), people with post-stroke dysphagia received 20 repetitions each of dynamic and static passive tongue stretching, 5 times a week for 4 weeks. They showed significant improvement in all areas of the oral phase of the swallow post-treatment, including bolus formation, containment, and oral transit time.

The patient sticks out their tongue while comfortably seated. The therapist uses dry gauze to hold the tongue with both hands. For the dynamic stretch, the therapist pulls the tongue out to the end of its range of motion, holds it for 2-3 seconds, then lets it return to the mouth. For the static stretch, the tongue is held for 20 seconds each time.

A systematic review of tongue strengthening exercises (Jannah et al., 2022) concluded that they are “significantly effective in increasing tongue strength” for older people, with the benefits of being low-cost and easy to perform. Tongue-to-palate resistance training (TPRT) is a way to build strength in the tongue. It can be done by pressing the tongue against the palate (Kim et al., 2017), or with resistance training equipment such as the IOPI (Park et al., 2015). You can also press the tongue left, right, and out against a tongue depressor (Clark et al., 2009).

Jaw Opening

The jaw, or mandible, provides essential support for oral control during swallowing. Studies have looked at jaw opening exercises for individuals with head and neck cancer (HNC) to prevent trismus, or restricted jaw opening. Trismus is a common side effect of radiation therapy caused by inflammation, hypoxia, endothelial injury, and fibrosis (Saghafi et al., 2024). Clinicians can use a jaw motion device (like the TheraBiteTM or JawTrainerTM) or tongue depressors for these exercises before, during, and after a radiation therapy course to improve mouth opening (Lee et al., 2018).

The mandible also impacts pharyngeal function. Jaw opening recruits the mylohyoid, geniohyoid, and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. Wada et al. (2012) found that jaw opening to the maximum extent resulted in improved upward movement of the hyoid, upper esophageal sphincter opening, and pharyngeal transit time for individuals with dysphagia.

Patients are instructed to “Open your mouth as wide as you can. Keep it open for 10 seconds.” This was done for 2 sets of 5 repetitions daily for 4 weeks in the research.

Jaw opening against resistance (JOAR) has been compared to the Shaker exercise (Choi et al., 2020). Both result in similarly improved suprahyoid muscle thickness and hyoid bone movement. Functional outcomes (like the PAS) have been used to support JOAR exercises for patients with dysphagia, though the amount of resistance needed is unclear (Park et al., 2020). Elastic bands can be used to build suprahyoid strength and tongue pressure in resistive jaw-opening exercises (Oh & Kwan, 2018).

Effortful Pitch Glide (EPG)

The effortful pitch glide (EPG) is a non-swallow exercise used to target laryngeal and pharyngeal muscles. It’s a combination of the falsetto exercise and the pharyngeal squeeze maneuver that were commonly used in the 1990s.

Patients make the “ee” sound starting at their natural pitch and gradually glide up the scale till they reach their highest pitch. They hold the highest “ee” sound forcefully for several seconds.

Miloro et al. (2014) reported that the biomechanics of the EPG are similar to swallowing in terms of anterior hyoid movement, hyolaryngeal approximation, laryngeal elevation, pharyngeal shortening, and lateral pharyngeal wall medialization based on dynamic MRI. Considering the overlap in physiology, it’s not surprising that reduced pitch elevation has been tied to reduced airway protection and dysphagia (Malandraki et al., 2011).

Some studies have included the EPG as part of a combination dysphagia exercise program. Balou et al. (2019) had participants produce 10 EPGs per set in addition to several other swallow exercises. Overall, the evidence for EPG is promising, but more research needs to be done with subjects with dysphagia that includes functional outcome measures with imaging.

Masako Maneuver

The Masako maneuver, or tongue-hold exercise, was one of the most commonly used dysphagia exercises for years. It targets the movement and strength of the posterior pharyngeal wall.

Patients are instructed: “Stick out your tongue. Gently hold it between your teeth. Swallow with your tongue out.”

This exercise can result in positive outcomes for patients with pharyngeal wall impairments confirmed by VFSS. Byeon (2016) found that the effects of the Masako maneuver were comparable to neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) for patients with dysphagia, and Söyer et al. (2024) reported increased submental muscle thickness and strength in healthy young adults. The Masako maneuver can be contraindicated for those with reduced hyoid movement or poor pharyngeal motility, and can result in negative effects like increased pharyngeal residue or increased delay in triggering the pharyngeal swallow (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, n.d.).

Tips to Make Progress with Swallowing Exercises

To see real improvement in swallowing, exercises should be assigned with neuroplasticity (Robbins et al., 2008) and motor learning principles in mind. These motor learning principles should be considered for dysphagia management (Zimmerman et al., 2020):

- More repetitions of an exercise are better than fewer repetitions

- Start with massed practice (repetitions in a short time) and then move to distributed practice (repetitions over a longer time)

- Practice the target in different contexts, like using different types of boluses

- Start with blocked practice (consecutive repetitions of the same target) and then move to randomized practice (e.g. alternating liquids and solids)

- Practice the whole movement instead of parts of the movement

- Focus on the outcome of the movement instead of the body part itself

- Focus on knowledge of results instead of knowledge of performance

- Provide feedback after several attempts instead of after every trial

- Provide delayed feedback rather than immediate feedback

- Encourage self-evaluation

Swallowing exercises are most effective when the patient understands not just how to do them, but why they matter. Patients with good adherence are more likely to tolerate a regular diet, are less likely to depend on a G-tube, and generally demonstrate a higher quality of life compared to patients with poor adherence (Zhu et al., 2022).

In a systematic review, Krekeler and colleagues (2017) highlighted several common barriers to adherence in dysphagia therapy. If your patient faces challenges, you can promote compliance by:

- Educating the patient on their impairments and the benefits of dysphagia therapy

- Providing written support, especially for multi-step exercises

- Using reminder tools or scheduling check-ins to monitor home exercise programs

- Encouraging social support through caregiver education, support groups, or possibly group intervention

Cite this article: Shahid, S. (2025, August). What SLPs Need to Know: Dysphagia Exercises. Tactus Therapy. https://tactustherapy.com/swallowing-exercises-dysphagia-treatment-slp/