Making Sense of Aphasia with a Sense of Adventure

7 min read

May 20, 2010. Around 3:00 am Byron fell out of bed, after going to a party the night before. I got up to check on him, but he appeared fine and flatly refused to go the emergency room when I suggested it. At 7:00 am, we got up and made coffee. Byron reached for a cup, and the coffee mug crashed to the floor. Something was wrong.

We arrived at the emergency room, and they told me he had a stroke. It had been too long since the first stroke symptom, falling out of bed, for Byron to get the clot-busting drug. They also told me he had Wernicke’s aphasia. I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew his speech made no sense.

At first I was told that all improvement would come within 90 days. Many families get this kind of information – it simply isn’t true. The truth is that improvement can always happen, and does, but it’s unlikely Byron will ever get back to 100%.

I started reading about aphasia. All of the books were hopeful but seemed to be about non-fluent aphasia. At that point, I didn’t realize the important difference. Byron had Wernicke’s aphasia, also called sensory, receptive, or fluent aphasia. He didn’t recover the same way as many of the stroke survivors with non-fluent aphasia. The phrase we heard over and over again was “such a pity that this brilliant man has aphasia.” I didn’t want pity. I wanted help.

Two Lives Changed Forever

Our life prior to the stroke was almost perfect. Byron graduated from MIT and Northwestern. He was a metallurgist with a specialty in corrosion, and his work gave us the opportunity to live 15 years in Saudi Arabia. Byron and I have always loved adventure – we’ve been around the world 11 times. At the time of the stroke, we were only a few weeks away from attending the golf tournament at Pebble Beach. We had also booked a cruise to Antarctica for later in the year. Neither of these trips happened.

Byron was an avid reader. Byron often chided me for reading the “fluff” stuff while he read non-fiction. Since the stroke, Byron can read, but a book can take him months. He’s more inclined to read some of my “fluff” stuff or the newspaper, which breaks my heart to see. I am grateful that at least he can read, since not everyone with aphasia can.

One thing Byron and I always had in common was great communication. We could talk to each other for hours about anything. Prior to the stroke, we had been married 37 years, and our communication never changed. Byron loved words, especially derivations, and he also loved theater, music, and art. In our relationship, Byron was the logical, strong one. He managed our finances and took care of the house and car – everything but the cooking. Byron is still logical, but I have had to become the strong one.

Aphasia Recovery Journey

In the first six months, Byron’s speech was mostly “word salad” – a mix of nonsense words typical of Wernicke’s aphasia. If I could hear two or three real words in a sentence, I was elated. He didn’t understand most of what I said, so we communicated through gestures and drawing. Soon Byron’s speech started including more swear words, even though this was not how he normally spoke. This was especially embarrassing in church. They let us stay members, but kindly suggested we sit in the back. Fortunately, the swearing soon subsided. Then Byron’s speech started to include more substitutions. For a long time whenever Byron could not say or find a word, he said “the leg.” The first two years, he had difficulty walking due to reduced feeling in his right leg. As his leg returned to normal, his speech substitution became “the hand,” perhaps because he has 3 numb fingers in his right hand. To this day it is still “the hand” or “the hand of the hand.”

We lost the majority of our friends. Our families tried to help, but they were so uncomfortable that it made things worse. We had two friends left who kindly took Byron out for lunch and a drive once a week. One speech pathologist suggested stimulating Byron with “sights and sounds,” so we started going on outings. With Byron’s love of theater, I took a chance and bought season tickets for some Broadway shows in Las Vegas. At first he tolerated the performances, and then he began to love them. Because many of the shows were revivals of ones he had previously seen, he gained confidence that he could follow along and understand. It was stimulating for him to be out exploring new places around town; our new adventure was learning to live with aphasia.

Around the middle of the third year, we discovered the Aphasia Recovery Connection (ARC). Since the stroke, Byron had really only conversed with SLPs and me. I will never forget the first time Byron met someone with aphasia at the ARC conference we attended. The look in his eyes said, “I am not a freak. I am not alone.” This was also the first time I discovered that Byron could read. A man with aphasia, who couldn’t speak, communicated by writing words on a whiteboard in capital letters. Byron could read these words! This discovery helped Byron regain his driver’s license as most road signs are in all caps. I will always be grateful for that conference and ARC.

By attending aphasia support lunch groups, I started to see a change in Byron. His spirit of adventure was coming back. He had a lot more “friends” than just the television. We took the chance to travel again with people who understood us, cruising down the California coast with ARC. We were finally able to see Pebble Beach. It was great to see Byron so happy – the stroke had no longer taken Pebble Beach from him.

Byron did have problems with some of the group sessions. At first, he thought that all aphasia was the same. He would ask me if he was “stupid” for not understanding like the others did. If no one in the group had Wernicke’s aphasia, he immediately wanted to leave. It has taken Byron a long time to learn that his aphasia is different. He is more comfortable talking to people one-on-one, and he hates being called on to answer in a group setting.

The Journey Continues

In the past few years, Byron attended more speech therapy. Unfortunately, it did not work so well for him. I hired a speech rehab assistant to work with him, but again saw no real progress. We also used Bungalow software for repetitive exercises, but he mastered those quickly. I felt like we were plateauing again and were at a crossroads. We had seen all but one of the speech therapists in Las Vegas, holding out on going to the last one, because it felt like it was the last chance at improvement.

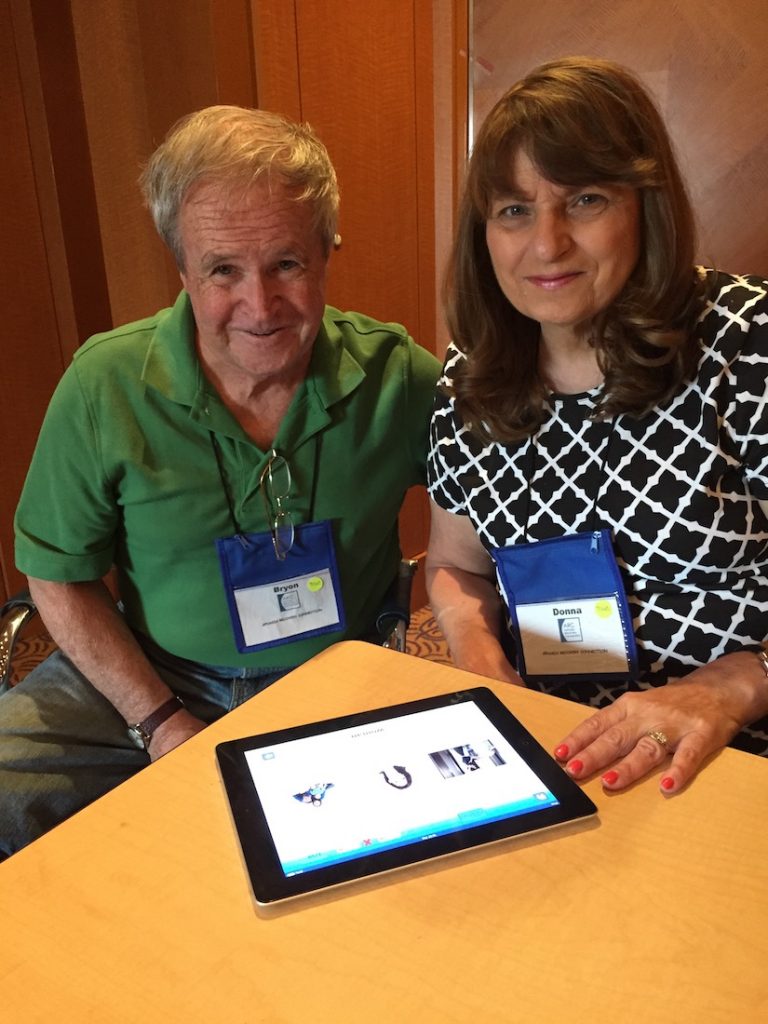

We signed up to go on the ARC cruise to Alaska, where the Tactus Therapy founder Megan Sutton would be meeting with people. We downloaded some sample apps from Tactus Therapy, and I worked with Byron a little before the cruise. He could do the exercises and seemed to like them, but I wasn’t really sure they were working. We met with Megan on the cruise where she explained not only how the software works, but how it can be incorporated into therapy for people with Wernicke’s aphasia. She understood that Byron needs repetition, and he connected with the programs.

We have decided to spend some time working with apps, and in the fall we’ll go back to traditional therapy. Because we know about Tactus Therapy and ARC, we are no longer afraid of taking that “last chance.” We view it as another adventure on the road to recovery.

With Wernicke’s aphasia, your options are sometimes limited. It can be easier to listen to someone with non-fluent aphasia searching for a word, as opposed to “word salad,” substitution, and sentences that sometimes make no sense. Fluent aphasia is hard on both the stroke survivor and caregiver, and it feels more isolating as there are fewer people who understand what it’s like. Sometimes therapy and aphasia support groups do not work for us. Not all software accommodates fluent aphasia. You have to search and continue to search to try all avenues.

Adventure On

Aphasia has been a long road and an adventure that I wouldn’t wish on anyone. Currently Byron understands over half of what he hears, and he can understand what he reads in a book or newspaper. Byron cannot spell or repeat words. He can read numbers, do math problems, make change, and analyze a financial statement better than I can. So from 0% comprehension and “word salad” to 60% comprehension and some functional language is not bad in 5 years. We have a long way to go, but the road is getting shorter all the time.

Never give up. Never accept “no” for an answer. Always keep searching for new ideas on aphasia. Don’t stay home. Be adventurous!

If you missed the post about fluent aphasia and Byron’s video, go check it out now! There’s no better way to understand than by seeing it for yourself.