Improving Cultural Competence: Better Serving the Needs of African American and Black Stroke Survivors in Speech Pathology

8 min read

I’m a 40-something white female, but the patients I serve as a medical speech-language pathologist rarely look like me. However, my colleagues do; the profession of speech pathology in the United States is 96% female and 92% white. Only 3.2% identify as Black. (Source: ASHA 2020 Member Survey)

In contrast, the US population is about 14% Black (including those who identify as multiracial). Of these 47 million Black Americans, well over half live in the South, a number that is growing after the “Great Migration,” which happened from the 1910s until the 1970s, up to northern cities like Washington D.C, Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago. This means that depending on where you live, you may have a much higher or lower percentage of Black folx in your community. (Source: Pew Research)

Black people in America have suffered under slavery, segregation, and racial discrimination ingrained in most societal systems. It should come as no surprise that healthcare is one of the systems that has treated Black people differently from whites. But what may be less obvious is that these systems have also resulted in differences in the health of Black individuals, including greater risk of stroke.

I had the unique opportunity to sit down with Dr. Davetrina Seles Gadson, an expert in aphasia and health disparities related to stroke, to find out what clinical speech pathologists should know about assessing and treating Black patients who have suffered a stroke and are experiencing aphasia or cognitive-communication impairments. Her answers can help all SLPs improve cultural competence in serving this population.

These are my questions, and the answers below are an edited and approved version of Dr. Gadson’s answers in our conversation, adapted for length and written format. The video clips summarize and expand on our first conversation.

A health disparity is a particular type of health difference that is closely linked to economic, social, or environmental disadvantage. This can pertain to a specific racial group, gender, age, or social-economic status. For example, Black Americans are twice as likely to have a recurrent stroke and have the highest death rate for stroke compared to any other ethnic group. They also have longer hospital stays, higher healthcare costs, and are referred more for speech therapy services than white stroke survivors with aphasia (Hardy 2019). Contributing factors like decreased access to healthcare facilities and longer hospital wait times are linked to these disparities.

By recognizing that health disparities exist, we can help to reduce their impact by trying to increase health equity. First, we need to recognize that some of the basic things white people of higher socioeconomic status take for granted may not be available. Nutrition may be poor because of “food deserts” in urban areas and the increasing cost of healthy foods. Environmental factors that have contributed to systematic racism in the urban areas are the lack of parks and gyms to support physical exercise and mental health. In addition, there are more liquor stores and targeted advertisements for unhealthy products.

SLPs can do our part to support health literacy by providing our patients with accessible educational materials. We can focus on medication management to avoid future hospital visits due to medication mistakes. We shouldn’t make assumptions about literacy skills. We just need to find out the level of independence the person had before, and help them get back to that type of autonomy.

Learn more about health literacy and writing accessible educational materials here, and find some easy-to-read accessible health information here.

Keep in mind that racial dynamics, past experiences, and AAE (African American English) dialectal features are all things that can influence an assessment. For example, in an assessment, you may observe poor eye contact, but if your client is an older Black male, consider the historic racism he may have experienced for displaying the behavior. The language we use in our reports should be objective, not judgemental.

We don’t want to attribute an error to a disorder when it’s simply a difference. Few standardized tests are normed on Black populations. For example, there’s a sentence in the Western Aphasia Battery that we ask patients to repeat: “no ifs, ands, or buts.” A Black person may omit the final “s”’s as a dialectal feature of AAE.

As practitioners, we need to become more sensitive and knowledgeable in dialectal variances and adjust scoring accordingly. We should also start holding assessment designers and publishers more accountable in ensuring that they’re including normative data for racial demographics.

Learn more about the linguistic characteristics of AAE or African American Vernacular English here.

Always start with building rapport. It’s important to gain the client’s trust so that they feel comfortable opening up and participating in therapy sessions. You can help build rapport by including them in the goal-setting process and always explaining rationales for why you’re doing what you’re doing.

Clinician-reported outcome measures, such as standardized tests, only tell us what’s wrong from a linguistic or impairment perspective. Use patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to measure progress and quality of life from the patient’s point of view, measuring the personal, participation, and environmental factors that are important to your client.

We know that motivation is the key to success, so we need to focus treatment on what the patient truly wants to work on. That will increase the likelihood of the patient following recommendations and practicing at home once they leave therapy. The patient must feel like they’re improving in ways that are meaningful to them.

As for therapy materials, representation is important. So pick photos that include Black people. Also, we need to keep therapy functional for the person’s needs. Rather than doing a planning activity for a theoretical trip to Paris, plan a realistic trip to the store using the local bus route or mode of transportation most familiar to the patient. We should accept answers that are given in AAE, but we don’t need to adapt therapy exercises to be delivered in AAE.

While every person is different, music is huge in Black culture. I often use a favorite song as a warm-up in therapy. Art is also very important. Many Black people have hobbies like playing card games or reading the Bible. Social interaction is so important. There’s a strong emphasis on fellowship that can be the focus of your person-centered goals.

Most individuals within the Black community band together in times of hardship, either through faith or community. This is no different for Black stroke survivors. Many will have strong community support.

The history of racism and systematic oppression in Black Americans may influence healthcare decision-making. Oftentimes when individuals come in for SLP services, they may say, “I don’t know why I came, the doctor just told me to come.” That’s paternalism, the view that the physician or other healthcare professional makes the decisions for the patient, not necessarily with the patient’s consent. That’s why it’s really important for us to focus on shared decision-making. It’s our role to say, “this is your therapy. I want to help you. What do you want to be able to do?”

Clinicians need to be careful of how they label certain behaviors, keeping historical and racial experiences in mind. Avoid loaded words like “non-compliant” or “refused”.

We all have biases and blind spots and no one can identify or address them but ourselves. The Preis 2013 study identified that the best way for white SLPs to address biases, discrimination, and power is for them to understand their own privilege.

Getting together in a safe and comfortable environment with other white people and having an open conversation is a great way to start to identify your biases. You may need to ask some uncomfortable questions and feel unsettled by the response, but that’s the only way to learn.

The key is making sure that you do the work. We should all want the best outcomes for our patients, so looking deep within ourselves to see how we might be subconsciously helping or hindering is worth the effort.

I didn’t know what terms to use, so I asked Dr. Gadson. Read her reply in this Instagram post about whether to use Black or African American.

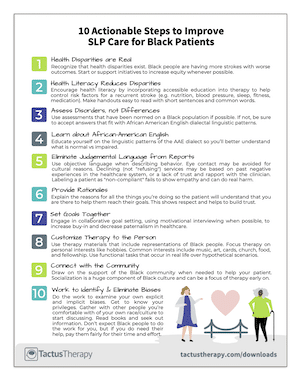

10 Things You Can Do to Improve Culturally-Responsive Care for Black Stroke Survivors

Download a free PDF handout that lists 10 Actionable Steps to Improve SLP Care for Black Patients. Use this handout to supplement your discussion of this article with your medical speech pathology team. What are you doing well? Where could you improve?

In addition to receiving your free download, you will also be added to our mailing list. You can unsubscribe at any time. Please make sure you read our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions.

References and Further Reading

Ellis, C., & Jacobs, M. (2021). The complexity of health disparities: more than just Black–White differences. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 6(1), 112-121.

https://pubs.asha.org/doi/abs/10.1044/2020_PERSP-20-00199

Ellis, C., Jacobs, M., & Kendall, D. (2021). The Impact of racism, power, privilege, and positionality on communication sciences and disorders research: time to reconceptualize and seek a pathway to equity. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 1-8.

https://pubs.asha.org/doi/abs/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-20-00346

Ellis, C., et al (2014). Racial/ethnic differences in poststroke rehabilitation outcomes. Stroke Research and Treatment, 2014.

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/srt/2014/950746/

Gadson, D. S., Wallace, G., Young, H. N., Vail, C., & Finn, P. (2021). The relationship between health-related quality of life, perceived social support, and social network size in African Americans with aphasia: a cross-sectional study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 1-10.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10749357.2021.1911749

Hardy, R. Y., Lindrooth, R. C., Peach, R. K., & Ellis, C. (2019). Urban-rural differences in service utilization and costs of care for racial-ethnic groups hospitalized with poststroke aphasia. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(2), 254-260.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003999318309286

Preis, J. (2013). The effects of teaching about White privilege in speech-language pathology. Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Populations, 20(2), 72-83.

https://pubs.asha.org/doi/abs/10.1044/cds20.2.72

Trimble, B., & Morgenstern, L. B. (2008). Stroke in minorities. Neurologic Clinics, 26(4), 1177-1190.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2621018/