What is

Dysphagia?

3 min read

Dysphagia (pronounced “dis-FAY-juh”, sometimes said “dis-FAH-zhuh”) means difficulty swallowing. Dysphagia can affect people throughout the lifespan, but more often impacts older adults, babies, or people with neurological problems.

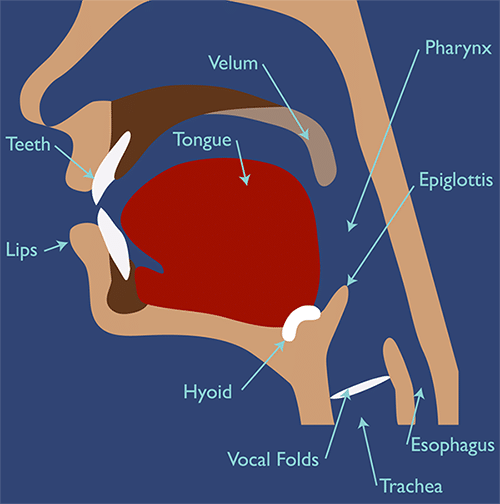

The muscles of the head and neck move intricately for many functions. Beyond articulating words with your tongue and lips, the muscles of the mouth and throat must work in synchrony in the essential process of swallowing.

These muscles are responsible for coordinating chewing, mixing food with saliva, moving food or liquid (called a bolus) from the lips to the back of the mouth, and then propelling it down the throat into the esophagus towards the stomach, bypassing the airway. Any difficulty in this process is called dysphagia.

What Causes Dysphagia?

Dysphagia is caused primarily by a weakness or impairment to one or more nerves or muscles that control sensation and movement for chewing and swallowing. Certain medications can cause dysphagia as well.

Dysphagia can occur as the result of a stroke, and may affect up to 65% of stroke patients. It can also be caused by aging, central nervous system diseases (such as dementia, Parkinson’s, MND/ALS, multiple sclerosis, or myasthenia gravis), gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD), radiation therapy, cleft lip and palate, dry mouth, cerebral palsy, inflammation of the esophagus, injury or surgery to the head and neck, and cancer.

The Process of Swallowing

Dysphagia can occur in different parts of the swallowing process. It could be an impairment in the ability to close your lips around food in the first place, or it could be interference with moving the food into your stomach.

Dysphagia can generally affect these three phases of swallowing:

- Oral Phase: Sucking, chewing, tasting, or moving a food or liquid within the mouth. Impairment is often caused by dry mouth, dental problems, muscle weakness, or difficulty coordinating the tongue, lips or cheeks.

- Pharyngeal Phase: Initiating the body’s swallowing reflex to squeeze food or liquids down the back of the throat and simultaneously closing off the airway to prevent aspiration (food or liquid in the airway). This phase is often impaired due to neurological damage.

- Esophageal Phase: Relaxing and tightening the esophagus to propel food or liquid down to the stomach. This phase may be affected by irritation or a blockage.

Signs and Symptoms of Dysphagia

Watch for and make note of any of the following signs that could indicate dysphagia:

- Coughing, throat clearing, or choking during or right after eating or drinking

- Wet-sounding voice during or after eating or drinking

- Extra effort, time, or pain with swallowing

- Food or liquid leaking from the mouth, getting stuck, or being held in the mouth (often the weaker side)

- Recurring pneumonia or chest congestion

- Weight loss or dehydration from not being able to eat or drink enough

- Difficulty swallowing medications

- Increasing difficulty eating independently

- Inability to contain saliva in the mouth (drooling)

A Serious Condition

Dysphagia can be a serious medical condition. Persistent difficulty in the process of swallowing can have a profound impact on a person, mentally and physically. Malnutrition, dehydration, and unintended weight loss can occur when it is difficult, slow, or painful to obtain the proper nutrients and fluids by mouth.

When food or liquid enters the airway, aspiration occurs and can lead to upper respiratory infections or pneumonia. It is important to note that after a stroke, sensation in the throat may be reduced; food or liquid may enter the lungs without the person’s knowledge and silent aspiration can occur.

Psychologically, dysphagia can result in a lack of pleasure or interest in eating, embarrassment when dining in a restaurant or around others, or isolation in social situations that involve eating. Modified-texture food and beverages may be difficult to obtain, expensive to purchase, or generally unappetizing.

If You Have Dysphagia

If you think you might have dysphagia, see your doctor for a referral to a speech-language pathologist (SLP). A SLP with expertise in swallowing disorders can determine if you are suffering from dysphagia by:

- Taking a thorough history of the signs, symptoms, and medical condition you are experiencing, also noting any medications you are taking.

- Performing an oral mechanism exam to evaluate the strength, sensation, and movement of your lips, tongue, cheeks, and larynx.

- Observing you during a meal or while swallowing liquids to note your behavior, posture, and oral movements.

- Performing a modified barium swallow study (MBSS, also known as VFSS) to observe your swallowing process under an x-ray called video fluoroscopy.

- Performing an endoscopic assessment (called FEES) using a lighted tube with a camera inserted through your nose to view the swallowing process.

Treatment for Dysphagia

Managing dysphagia with the expertise of a speech-language pathologist can help people improve the impairments responsible for the dysphagia or utilize techniques to help compensate for lost function.

A dietician may be part of the process to recommend nutritional options to reverse or avoid malnutrition. An occupational therapist may also advise on adaptive tools or positioning to make eating easier. A gastroenterologist will be part of the team if the swallowing problem involves the esophagus.

Treatment for dysphagia may include:

- Techniques to improve swallowing. A SLP may prescribe exercises or maneuvers to strengthen the muscles or stimulate the nerves in the mouth and neck.

- Strategies to decrease the impact of dysphagia. The SLP may recommend techniques such as changing the position of the head while swallowing or swallowing multiple times.

Dysphagia Therapy is an app to help clinicians find the best options for swallowing therapy based on the impairments they’ve diagnosed.

- Modifying the texture of foods and liquids. Diet modifications such as thickening liquids to a nectar-like consistency or pureeing foods in a blender can help a person with dysphagia maintain proper nutrition while making it easier to eat or safer to swallow. Eliminating more challenging textures, such as crackers, rice, or certain soups, may be recommended. In extreme circumstances, a period of no oral intake (NPO) or a feeding tube may be required.

- Modifying the feeding environment. Removing distractions, such as turning off the TV, can help a person with dysphagia concentrate on the task at hand. The person should be encouraged to take small bites or sips within a slow and relaxed mealtime. Proper support to keep the person fully upright when eating is almost always recommended. Food should be presented attractively to make it more appealing. Special utensils, plates, straws, or cups may be needed to allow for self-feeding.

- General self-care. Keeping the mouth clean and free of bacteria is one of the best ways to avoid chest infections when a person has dysphagia. Also, moving around and being active can help the body fight infection if anything does go down the wrong way.

While the stress of swallowing impairment can be great, the right therapy, trained caregivers, a safe diet, and appropriate strategies can make living with swallowing disorders more manageable.

Tactus Therapy understands the challenges of swallowing disorders and is providing clinical teams with new and valuable solutions to dysphagia management. Visit our Dysphagia page in our Learn section to discover helpful resources and learn about our Dysphagia Therapy app.