10 Aphasia Myths Busted

15 min read

Here are some common misconceptions about aphasia and the true story behind them. Please share these aphasia myths to help others understand aphasia better.

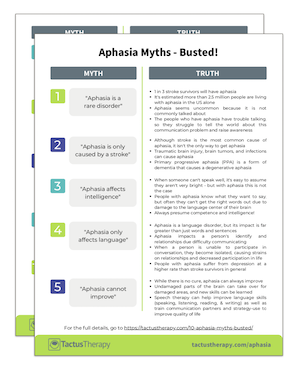

Myth 1) Aphasia is a rare disorder.

Truth: While you may not hear much about aphasia, it’s certainly not rare. One in three stroke survivors will have aphasia (at least initially), and it’s estimated that more than 2.5 million people are living with aphasia in the US alone. More people have aphasia than Parkinson’s disease.

So why does it seem so uncommon?

The people who have aphasia have trouble talking. They struggle to tell you about this communication problem they have because they have a communication problem. It’s a vicious cycle that keeps you from hearing much about aphasia.

Aphasia is often one of many problems people experience after a stroke or brain injury – they also have paralysis, mobility problems, and depression. These things combine to keep people with aphasia at home and socially isolated. They’re not out in the public spotlight and rarely on social media, but rather in clinics and in care homes, focusing on their recovery.

There are public figures who have or have had aphasia (musician Randy Travis, actress Patricia Neal, Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower are a few), but the word is not always used in the reporting. We hear they’ve suffered a stroke and can’t talk. The news doesn’t use the word “aphasia,” maybe because they think nobody knows what it is. Again, a cycle – but one we have the power to break.

Download the handout to share!

Get your free 2-page PDF handout of 10 Aphasia Myths – Busted! We’ve summarized all these myths for you in an easy-to-read handout that is perfect to share.

In addition to receiving your free download, you will also be added to our mailing list. You can unsubscribe at any time. Please make sure you read our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions.

Myth 2) Aphasia is only caused by a stroke.

Truth: Stroke is the most common cause of aphasia. This is because aphasia happens when the language center of the brain is damaged, and a stroke often damages a specific area of the brain when blood flow is cut off.

But a stroke isn’t the only way to get aphasia.

Sometimes a traumatic brain injury will cause aphasia if the impact is more focused. Brain tumors, infections, and inflammation can cause aphasia if they impact the language areas. Sometimes even a migraine headache can be so bad as to cause aphasia temporarily.

There is another kind of aphasia that has a different cause and trajectory. It’s called primary progressive aphasia (PPA), and it is a degenerative condition. PPA is a form of dementia that strikes language before other cognitive skills as it progresses. While stroke or brain injury survivors with aphasia often get better, those with PPA will lose language function over time.

As with any condition, people with similar causes of aphasia often relate better to each other. A family member of a person with PPA will face different challenges than one who is dealing with the aftermath of a stroke. A person who suffered a traumatic brain injury may not have the same physical symptoms that stroke survivors have.

Not all problems finding words, understanding, or communicating are aphasia. People who are experiencing these difficulties sometimes hear about aphasia and think they have it. However, if it did not come on suddenly as a result of a brain injury, or it isn’t getting worse as part of PPA, it probably isn’t aphasia. An in-depth assessment by a speech-language pathologist will help to tease apart the roles of language, speech, and cognition in any communication problem.

Myth 3) Aphasia affects intelligence.

Truth: When someone can’t speak well, it’s easy to assume they aren’t very bright. However, with aphasia, this simply isn’t true. People with aphasia are as intelligent as they were before they got aphasia. Since aphasia is a result of damage to the language center of the brain, it doesn’t affect what people know or how they think.

People with aphasia know what they want to say. They have the same ideas, emotions and thoughts as you do. They have advice to give – jokes and stories to tell. All these messages are trapped inside a brain that won’t let them out like it used to. Only the keywords come out, the timing is off, or the wrong words are spoken. Imagine how FRUSTRATING that must be!

What makes this worse is that often people with aphasia are afraid that you’ll think they’re not smart, so they don’t even try for fear you’ll judge them. This is why some of the most powerful words we can say to a person with aphasia who is struggling are: “I KNOW YOU KNOW.” This simple act of acknowledging their intelligence can put the person with aphasia at ease.

Now here’s the complicated part. Aphasia does not affect intelligence. But…

Some people who have aphasia ALSO have cognitive impairments. The same brain injury that caused the aphasia may have impacted other parts of the brain –parts used for attention, memory, reasoning, and executive functioning.

Family members might notice cognitive and language problems, but they keep hearing that aphasia does not affect intelligence, so they are confused. It’s important to recognize this because the research tells us that cognition plays a big role in aphasia recovery. Those better at problem-solving are often better at finding ways to communicate. People who struggle with memory aren’t as able to remember the strategies they learn in therapy.

So what do we do with this information?

Presume competence. Go into every interaction with a person with aphasia assuming they are as intelligent as ever and treat them so. But when clinicians are assessing, they should test for cognitive skills that may help or hinder therapy and address them accordingly.

Myth 4) Aphasia only affects language.

Truth: While it’s true that aphasia is a language disorder, its impact is far greater than just words and sentences. Aphasia experts Aura Kagan and Nina Simmons-Mackie offer this as a more accurate definition:

“Aphasia is a communication impairment that impacts identity and relationships because of difficulties speaking, understanding, reading, and writing.”

Dr. Simmons-Mackie went on to describe aphasia further:

“Aphasia disrupts communication – the core of our ability to develop and maintain relationships, take part in home and community events, and project a public image of ‘who we are.’ Communication is essential to almost all of our activities of daily living. ‘Without the ability to participate in conversation, every relationship, every life role, and almost every life activity, is at huge risk. When adding problems with reading and writing, the impact is devastating. This results not only in barriers to accessing healthcare services and information, but also inevitably leads to a loss of self-esteem and a profound sense of social isolation.”

Wow. When you stop to think about how communication defines us, connects us, and gives us purpose, you start to realize how devasting it might be to lose that ability.

It’s no wonder that people with aphasia suffer from depression at a higher rate than stroke survivors in general. Decreased language leads to decreased participation which leads to decreased socialization…. a dark and lonely path to travel.

As much as people with aphasia need to improve their word finding and sentence comprehension, they also need to boost their confidence, maintain hope, and find purpose. Speech therapy can and should focus on both the communication impairments and the impact. Aphasia groups can provide a safe space to socialize, connect with others, and practice. Greater awareness of aphasia in society at large would enable those with aphasia to feel more comfortable trying and sometimes failing, without fear of being judged harshly.

Don’t stop with just the word aphasia and the linguistic impairments when raising awareness. Highlight the emotional impact as well – on identity and relationships.

Myth 5) Aphasia cannot improve.

Truth: While there is no cure, aphasia can always improve. People used to believe that brain damage was permanent, but we now know that’s simply not true. Undamaged parts can take over for the damaged area, and new skills can be learned. We are understanding more about experience-dependent neuroplasticity – the brain’s ability to change based on what we do.

Recovering lost skills and learning new ways of doing things is the purpose of rehabilitation. Stroke survivors and others with aphasia participate in speech therapy to improve their communication skills. The speech therapist (or speech-language pathologist, SLP) guides the person with aphasia through exercises designed to strengthen skills related to speaking, listening, reading, and writing.

Speech therapy exercises must be repeated over and over to form new pathways in the brain. The work should be relevant to the person’s needs to keep them engaged. Exercises should provide just the right level of challenge to avoid frustration. Therapy can be done in-person at a hospital or clinic, or at home with technology such as apps.

A study done at Cambridge looked at stroke survivors with chronic aphasia (more than 1-year post-stroke) who used a speech therapy app called Language Therapy 4-in-1 every day for a month. Researchers found that everyone who used the app made significant progress on a test of language abilities, and those who played a game for the same amount of time did not. This is wonderful news for people with aphasia who want more therapy – it’s available and it works!

While it is true that many people with aphasia do not make a full recovery, everyone with aphasia can make progress on their goals. They just need the right exercises or strategies, motivation to work hard, people to support them, and intensive practice.

“Never discourage anyone who continually makes progress, no matter how slow.” – Plato

Myth 6) Aphasia either affects your speech or your understanding.

Truth: Aphasia can affect both speech and understanding to varying degrees. This myth comes from aphasia often being divided into two types: expressive aphasia and receptive aphasia.

This makes people think that those with expressive aphasia (Broca’s aphasia) can understand just fine. But in reality, while understanding is much stronger than speaking in this type of aphasia, there are still problems with both.

People with receptive aphasia (Wernicke’s aphasia) have a lot of trouble understanding, but they also can’t express themselves well either. While their speech is often fluent and effortless, it doesn’t make sense and contains a lot of the wrong or made-up words.

Most people with aphasia have trouble in all four areas of language to some degree or another. While a person may be stronger at reading than writing, they may still struggle to read the same novel-length books they used to enjoy. Those who appear to understand well may be relying more on the context of the situation than the words and grammar. A sentence like “She was given the ball by him” may be easily misunderstood.

Advanced Language Therapy offers higher-level exercises for people with aphasia who appear to do well on basic tasks. Advanced Comprehension Therapy (part of Advanced Language Therapy) contains sentences like the one above to challenge understanding at the sentence level.

If you don’t know how well a person with aphasia understands, it’s okay to ask. It never hurts to simplify your speech. Just don’t talk down or talk louder – that doesn’t help. Establishing the topic and writing down keywords can help a person understand.

For people who have a hard time talking, give them time, offer choices, or ask if writing or drawing will help. Never fill in the words for them unless they say it’s okay. Some people carry cards that explain what they have trouble with and how to help.

Myth 7) Aphasia only affects oral communication, not written.

Truth: Aphasia can affect any or all of the four ways we communicate with language: speaking, understanding, reading, and writing. Each can be affected differently, and it’s not possible to know just by talking to someone how well they can read or write.

The most frequent question that YouTube viewers ask on our two popular videos showing two men with Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia is “can they write what they want to say?”

Unfortunately, no.

That’s a key difference between speech and language. Someone who has a speech problem probably can write what they want to say. But someone with a language problem – like aphasia – cannot.

Speech is a physical act that takes air from the lungs, vibrates it in the voice box, and shapes it in the mouth and nose to create a series of sounds. Someone who has laryngitis, a tumor in their throat, or weakness in their tongue might have a speech problem. Language is the words we use and how we combine them, and language happens in the brain. It doesn’t matter if it’s spoken or written, if you can’t think of the word you want, you can’t communicate it.

Some people with aphasia also have a speech problem called apraxia. When apraxia is the factor limiting their communication, then writing might work better than speaking. Some people with aphasia and apraxia communicate quite well in writing. You just can’t assume – it’s different for everyone.

All this variability means there’s no easy solution for helping someone get their message out. Some people can use devices or apps that have stored messages, and they use their reading skills to select the message they want. Others can write or type out words or short phrases. The more severe the aphasia, the harder it is to get the message out via any means.

Numbers and gestures can also be impaired with aphasia. The language center of the brain processes all symbols, so it’s not just words. This means that real pictures might be easier to interpret than icons, and both saying and understanding numbers can be hard.

Tactus Therapy has apps for all areas of impairment: speaking, understanding, reading, writing, and numbers. Use our App Finder to find the right app for your needs.

Myth 8) Aphasia affects only the person whose language is impaired.

Truth: As devastating as it is to lose your ability to communicate, it is similarly heartbreaking when it happens to someone you love. Imagine you can never again have a normal conversation with your husband or wife. You are suddenly thrust into the role of caregiver, and all household and life responsibilities now fall on your already-busy shoulders. You’re not the one who suffered the stroke, but you are also suffering.

Aphasia impacts everyone in the life of the PWA (person with aphasia). All close family members and friends experience a loss of the relationship they once had with the PWA. While the PWA has not changed who they are, the way they share their thoughts and engage with others has been changed by the aphasia.

Aphasia best practice recommendations state that all people affected by aphasia should receive services. This means that families and caregivers need to have education, counseling, and training on how to communicate with their loved one. They should be included in therapy and have access to respite.

The National Aphasia Association has a Caregiver’s Bill of Rights that offers support for many concerns caregivers face.

It’s so important for caregivers to take care of themselves as well as their PWA, because “you can’t pour from an empty cup”. Friends often disappear after aphasia because it’s hard to hang out with someone who doesn’t talk. This leaves even more burden on the family or caregiver as there are fewer social supports to share the load.

One of the great side effects of aphasia community groups is that often the care partners are not allowed to join, so they form their own groups and get enormous benefit from talking with others in the same situation. If you are in the position of aphasia caregiver, seek out others like you in person or online. Having the space to release frustration and sadness, away from your PWA who might take it personally, can be powerful.

The Aphasia Recovery Connection has online groups for people with aphasia as well as just for care partners to connect.

We’ve already learned that aphasia takes away more than just language – it also affects relationships. A relationship is more than one person, so we must acknowledge all people who mourn the change in that connection.

Myth 9) Aphasia is the same for everyone.

Truth: When you’ve met one person with aphasia, you’ve met one person with aphasia. Aphasia is different for everybody.

As we’ve already learned: speech, understanding, reading, and writing can all be affected differently. And even with the same level of impairment in one of those areas, people may compensate or react differently.

One person may suffer from depression, while another seems almost unfazed. Mental health is an important factor in stroke and aphasia recovery.

Some people with aphasia keep trying to communicate, while others withdraw. Personality and confidence can play huge roles in the impact aphasia has on a person’s life.

One person with aphasia may be a good problem solver, pulling up photos, maps, and other tools to help communicate; another may not know what to do when the words don’t work.

And we must remember – communication happens between two people. The conversation partner plays a HUGE role in determining how successful the exchange is between people. A skilled partner can use tools and strategies to help get their message in, help the person with aphasia get their message out, and reveal their competence. (Look at the SCA – Supported Conversation for Adults with Aphasia – program from the Aphasia Institute to learn these tools.)

So aphasia can vary based on the severity of impairments, relative strengths in different areas of language, mental health, cognitive skills, personality, confidence, and skill of the communication partner. That’s a lot of variables that make each person’s aphasia unique.

Myth 10) Aphasia doesn’t affect you.

Truth: You likely already know someone who has aphasia, or you will as you age. Incidence of stroke is increasing along with survival rates, which means more people are living with aphasia. An estimated 2.5-4 million Americans have aphasia, meaning roughly 1 in every 100 people.

Even if you don’t know anyone personally who has aphasia yet, you still bear the cost. Health care costs are higher for people with aphasia, and the risk of medical errors is much higher for those with communication problems. Whether you pay into insurance or contribute to a public system, these costs make healthcare more expensive for everyone.

Research from Hurtig et al in 2018 states, “reducing communication barriers could lead to an estimated reduction of 671,440 preventable [adverse event] cases and a cost savings of $6.8 billion annually [in the U.S.].” Six point eight BILLION – just because people can’t communicate. They can’t say when they’re in pain or when they’re experiencing a bad reaction to a medication; they fall more when they can’t communicate their need to get up or have something brought to them.

Outside the medical system, people with aphasia are less likely to return to work than other stroke survivors. They may also require more caregiver support, straining their partner’s ability to work outside the home.

The good news is that if we make our society more accessible to people with aphasia, they can be more independent. Just as we have installed ramps for physical access, we can put in supports for communication access. Things like picture menus, simplified text on forms, and trained communication partners can make a big difference.

When we modify the environment to help one group, we often make life easier for others. Curb cuts not only allow wheelchair users access to the sidewalk, but also delivery carts. Closed captioning on TV is now used by more than Deaf and hard of hearing people. Aphasia-friendly print materials would help people with low literacy, those just learning English, and people with dementia.

Share these myths on your social media account to help spread #aphasiaawareness so we can all #talkaboutaphasia.