What SLPs Need to Know:

Auditory Comprehension

9 min read

The classic aphasia classification chart implies that auditory comprehension is all or nothing – impaired or intact. Most clinicians learned in school that aphasia is either receptive (trouble understanding) or expressive (trouble talking). In reality, most people with aphasia have trouble understanding spoken language to some extent, even those with primarily expressive impairments.

While a more accurate division of aphasia types may be fluent or non-fluent, it’s important to fully assess auditory comprehension no matter the diagnosis. You might write off a comprehension impairment if a patient is responding to questions correctly, but if their answers are hesitant, slow, or self-corrected, there may be a mild deficit (Helm-Estabrooks, 2011).

Understanding Auditory Comprehension

Auditory comprehension, or understanding what you hear, relies on both language and cognitive skills. It’s up to the speech-language pathologist to assess the relative strength of comprehension, as well as what’s causing the impairment.

A breakdown in language may be in one or more of these linguistic components:

- Phonology: recognizing a string of sounds as a word

- Semantics: associating words with their meanings

- Syntax: understanding various sentence structures (e.g., passive voice) and aspects of grammar (e.g., pronouns) in a sentence

Cognitive skills, like attention and working memory, also play an important role in understanding spoken information, especially at the sentence and discourse level (Wallace et al., 2022). You must sustain attention to the spoken information, ignore distractions, and remember the first part of what you heard to understand the rest.

Read more about aphasia and attention and general attention treatments in our What SLPs Need to Know series.

The interplay between language and cognition is why we also see difficulties with auditory comprehension in conditions that primarily impact cognition, not just in aphasia. People with traumatic brain injuries, dementia, and right hemisphere stroke frequently struggle to understand, especially when listening to long or complex information, as part of their cognitive-communication disorder.

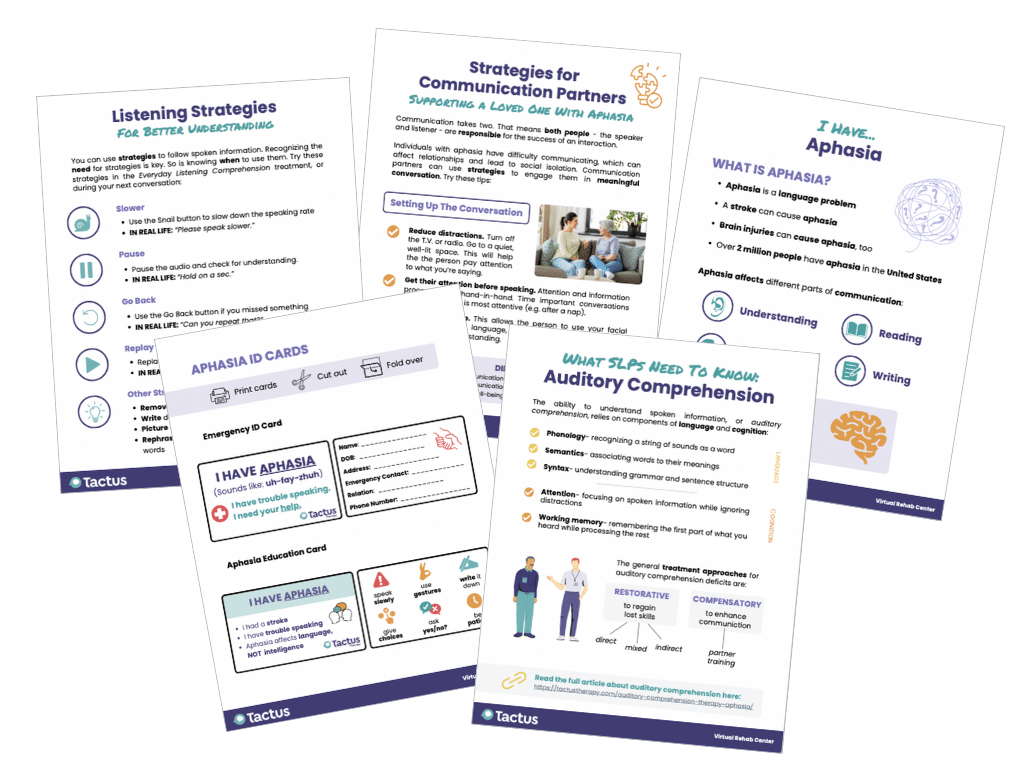

Looking for Printable Resources?

Unlock the Handout Vault

Dozens of high-quality, well-researched PDF handouts are available all in one place: The Tactus Virtual Rehab Center!

Patient education, home practice, clinical guides, visual supports, & a summary of this article for quick reference.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Access 50+ evidence-based treatments and 90+ handouts created specifically for adult medical speech-language pathologists.

Why Auditory Comprehension Matters

Auditory comprehension abilities are closely tied to rehabilitation outcomes, making this a sensible place to begin therapy. Most rehab interventions, such as physical and occupational therapy, require the patient to follow spoken directions. If a patient is having trouble understanding what they need to do and why, therapy will be less effective. Understanding is also deeply connected to quality of life and participation in activities after the rehab process is over (Wallace et al., 2022).

The evidence for auditory comprehension treatments is variable, but research does show that a variety of treatments have improved auditory comprehension in certain people (Wallace et al., 2022), and patients can improve their auditory comprehension beyond the first year post-stroke (Lwi et al., 2021). This makes auditory comprehension a good target for speech therapy in inpatient or outpatient rehab.

Auditory comprehension impairments are a hallmark of fluent aphasia. Learn more about two treatment techniques specific to fluent aphasia in How To: Treat Wernicke’s Aphasia.

Treating Auditory Comprehension: An Overview

Approaches for auditory comprehension therapy can generally be divided into restorative treatments aimed at regaining skills and compensatory treatments to enhance functional communication.

Restorative treatments for auditory comprehension can be divided into three categories:

- Direct treatment: Includes spoken input and non-verbal responses.

- Mixed treatment: Includes other input modalities besides auditory (e.g., writing or gesture). Responses can be verbal or non-verbal to work on simultaneous language goals.

- Indirect treatment: Focuses on other skills (e.g., attention, working memory) to indirectly improve auditory comprehension.

Direct Restorative Treatment

Direct treatment, or the “traditional stimulation approach,” was introduced by Hildred Schuell and colleagues in the 1960s. It’s probably what you’re most familiar with, since Schuell’s Stimulation Approach (SSA) has been standard practice for many years. It includes activities in a drill format, delivered intensively to restore skills, like:

- Verification tasks: “Is this a hospital?”

- Following commands: “Make a fist, then point to your nose.”

- Identifying items or pictures: “Point to the pencil.”

Direct treatment activities have multiple advantages. They are accessible for patients with limited or effortful verbal output, they can inform clinicians on patients’ phonological and semantic skills, and they can indicate a patient’s overall auditory comprehension skills (Durfee & Harnish, 2022).

Morris & Franklin (2012) used a name-picture verification treatment with two participants with aphasia. One participant improved on trained and untrained items, but the other did not. Knollman-Porter et al. (2018) used a high-intensity name-picture verification treatment with two participants with chronic, severe aphasia. Both participants improved on the trained stimuli. Large effect sizes were reported on untrained stimuli, indicating generalization. Immediate and consistent feedback was provided to address self-awareness.

The Virtual Rehab Center has two name-to-picture verification tasks: Spoken Word Decision and Spoken Compound Word Decision. Each has several levels of difficulty.

In a scoping review of auditory comprehension studies, direct treatment generally resulted in positive change for “all or some participants” on trained and untrained stimuli (Wallace et al., 2022). The review was encouraging, but not all studies reported generalization or statistical significance, and most had a very small sample size. It’s clear that researchers need stronger study designs to guide clinicians in the right direction.

Direct Comprehension Therapy:

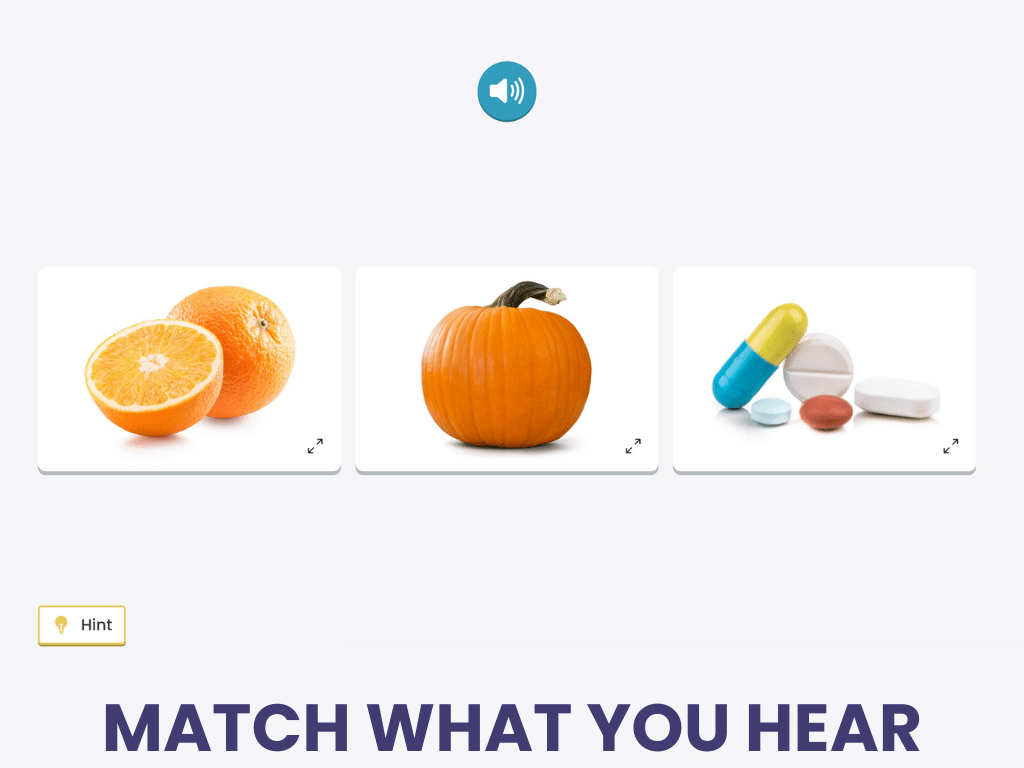

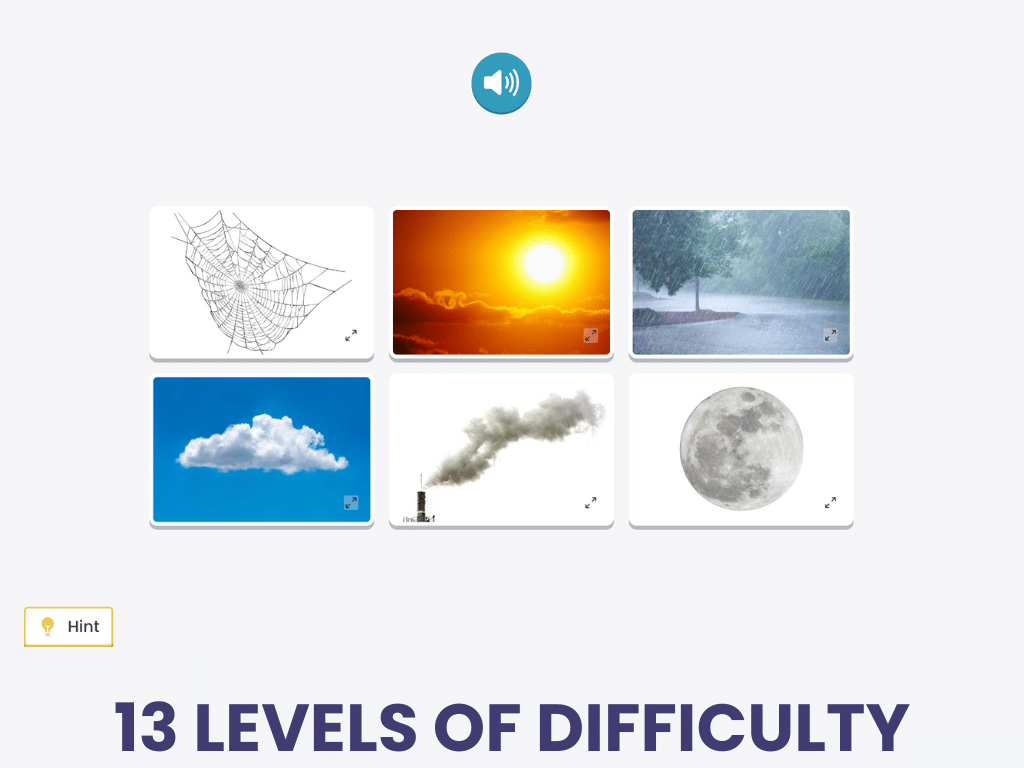

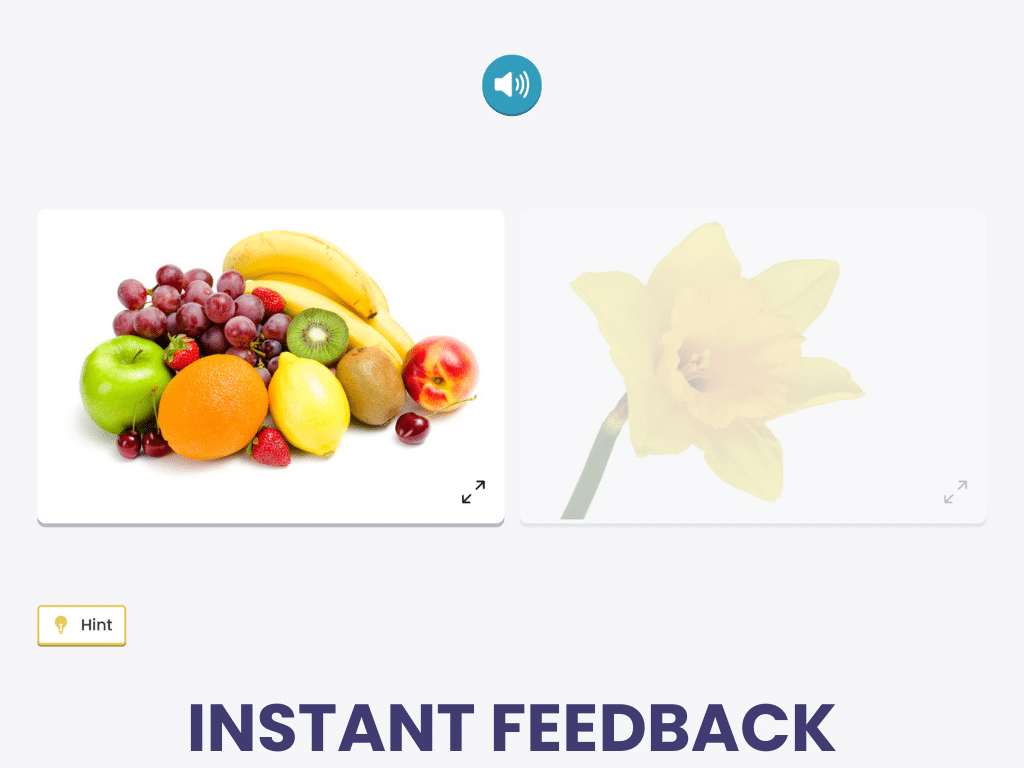

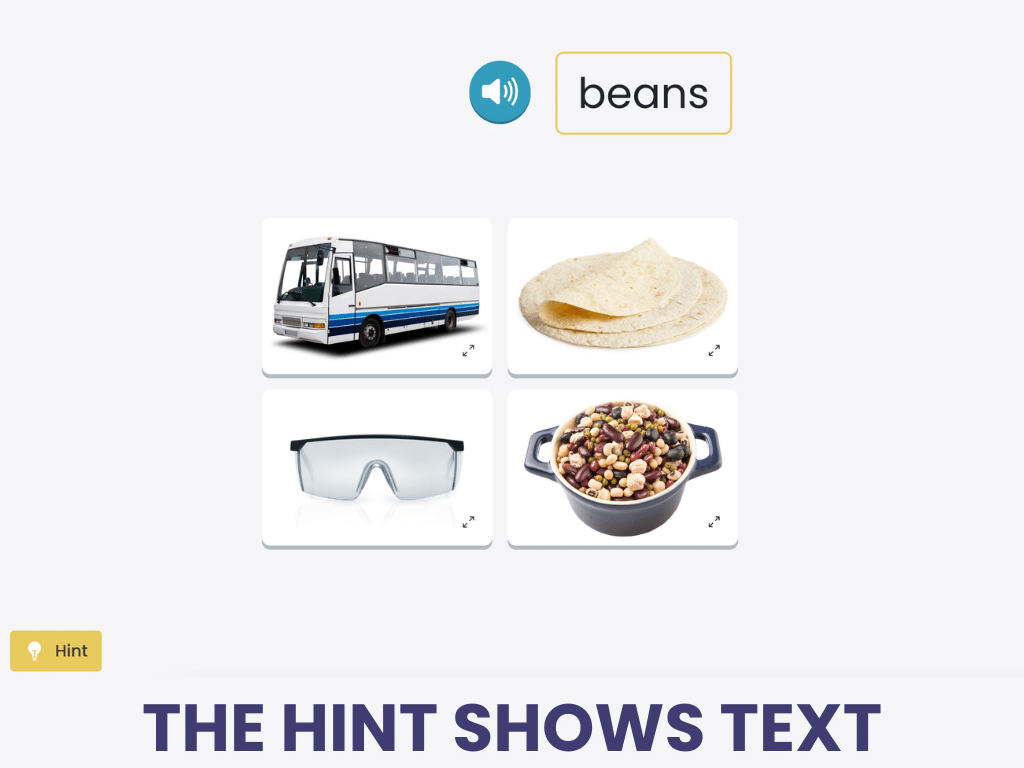

Identifying Spoken Words

Identifying Spoken Words is a spoken word-to-picture matching task using imageable nouns.

Clinicians can add a verbal errorless learning component by asking the patient to repeat the target word, transforming it into a mixed treatment that targets multiple language goals.

Identifying Spoken Words is a listening treatment in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

Use technology to present stimuli of just the right difficulty, provide feedback, adjust complexity, and score the performance – even write the SOAP note! You provide the cues and add to the cognitive load.

Mixed Restorative Treatment

There are more studies that describe mixed treatments, with different input modalities (e.g. writing, gestures) and response types (e.g., verbal, writing). Examples include:

- Written word to picture matching

- Picture naming

- Treatment of Underlying Forms (TUF)

Marsalisi et al. (2023) delivered SSA intensively to two people with severe and chronic fluent aphasia. This study involved an auditory comprehension block and a verbal production block, classifying it as a mixed treatment. Tasks included identification (“point to the…”), one-step directions, yes-no verification, and naming using a cueing hierarchy. Both participants improved, but with limited generalization.

Computerized therapy can lead to significant improvements in auditory comprehension, likely because it allows more intensive practice than in-person therapy alone (Fleming et al., 2021). A study found that 85 hours of practice on a tablet-based therapy app resulted in item-specific gains that were maintained 24 weeks after therapy for people with aphasia. Another computer-based treatment found improvement in auditory information processing after 40 one-hour training sessions with cognitive exercises (Voelbel et al., 2021).

Raymer et al. (2006) described another computerized treatment involving spoken/written picture matching and rehearsal. Two of five participants in this study presented with comprehension deficits. Both demonstrated improved verification post-treatment, more for trained items than untrained items. All five participants with word-retrieval deficits showed improvements in picture naming post-treatment.

Treat Functional Comprehension:

Understanding Spoken Directions

Understanding Spoken Directions asks patients to match verbal one-step directions to a picture given a field of choices.

Remember, you can maximize outcomes by assigning treatments for intensive home practice since “more frequent training leads to greater improvements during acquisition than less frequent training” (Raymer et al., 2006).

Understanding Spoken Directions is a listening treatment in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

We know that practicing functional targets leads to better generalization in real life, so we make our treatment stimuli resemble the things people hear in daily life.

Treatment of Underlying Forms (TUF) is a syntax-based treatment intended to improve auditory comprehension and sentence production. It involves transforming simple sentences into complex ones that can be trained under the premise that training complex sentences first will generalize to simpler sentence types (Thompson, 2001). A meta-analysis by Swiderski et al. (2021) found that TUF showed greater gains for people with milder aphasia.

The review by Wallace et al. (2022) reported that mixed treatments generally resulted in positive change for “all or some participants” on trained and untrained stimuli, but with similar design limitations as the direct treatment studies.

Indirect Restorative Treatment

Indirect treatments for auditory comprehension are gaining attention in the literature. We’ve already discussed that understanding spoken language requires both language and cognitive skills, so it’s exciting that research suggests that treating cognition can result in improved auditory comprehension (called far transfer effects).

Helm-Estabrooks et al. (2013) outlined the Cognitive Approach to Improving Auditory Comprehension (CAIAC) using stimuli that do not require verbal output or auditory comprehension. They used tasks from the Cognitive Linguistic Task Book (CLTB), which evolved into the Attention Training Program (ATP), and finally into the Problem Solving Therapy Program (PSTP). All participants with chronic aphasia demonstrated improvements in auditory comprehension in initial studies.

Studies have examined Attention Process Training (APT) to figure out if attention, specifically, is the key to success when it comes to comprehension. Murray et al. (2006) treated a person with conduction aphasia and mild auditory comprehension deficits using APT-II, which included linguistic stimuli. Gains in auditory comprehension were minimal, although deficits were mild to start with.

Working memory treatment is another cognitive contender in the auditory comprehension space. Examples of verbal working memory treatments include sentence repetition, sentence reconstruction, listening span tasks, N-back, and mental math. Nikravesh et al. (2021) used a working memory training program for participants with mild-to-moderate Broca’s aphasia. They noted significant improvements in auditory comprehension following working memory training.

The Virtual Rehab Center features a treatment called Verbal Working Memory that is based on the Nikravesh et al. (2021) findings of how effective reverse digit span treatment can be in far transfer effects to aphasia.

In a systematic review of working memory treatments, 77% included outcome measures for spoken sentence comprehension based on the strong association between working memory and language. These studies also reported improvements in auditory comprehension following working memory training (Zakariás et al., 2019).

Metacognitive strategy training (MST) is standard treatment for cognition, but it requires good understanding. Kersey et al. (2021) found that participants with mild-moderate aphasia benefited from MST adapted with supportive conversation methods to aid understanding. This means MST could be a reasonable treatment option for some (not all) patients with comprehension deficits.

Higher-Level Therapy:

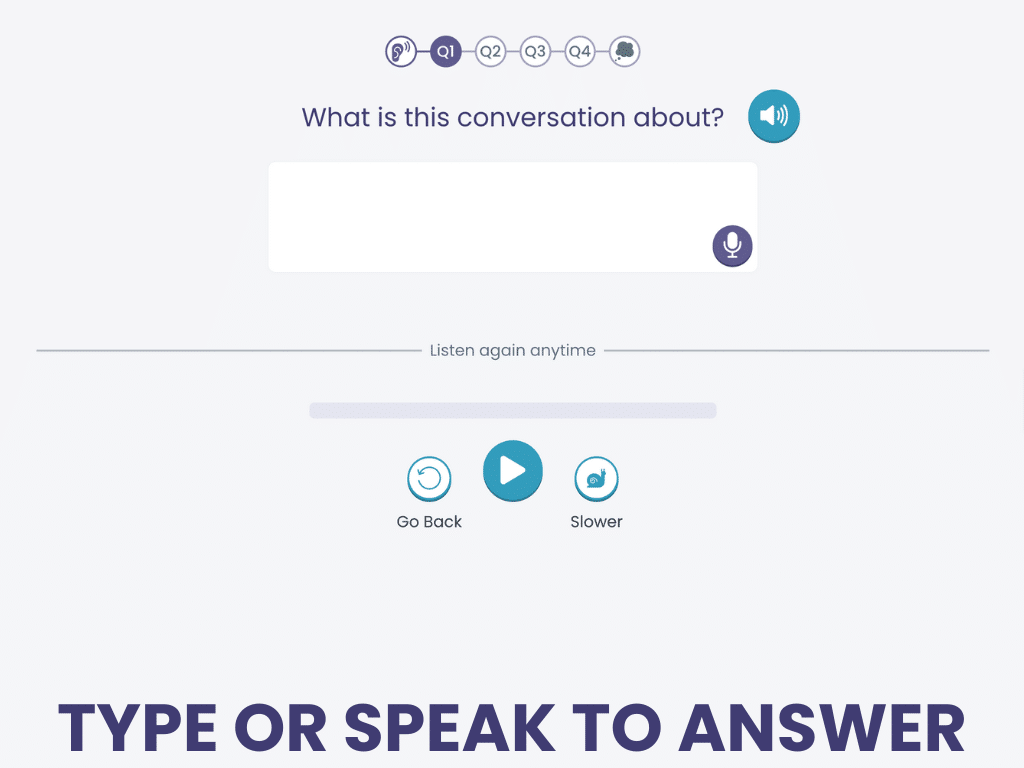

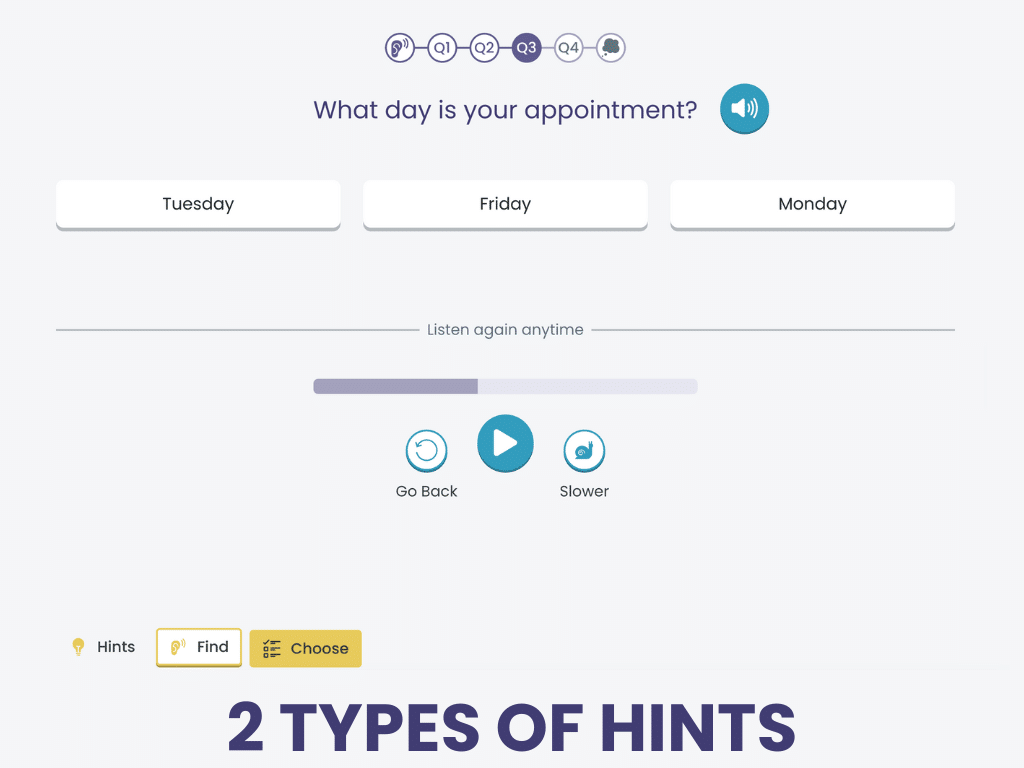

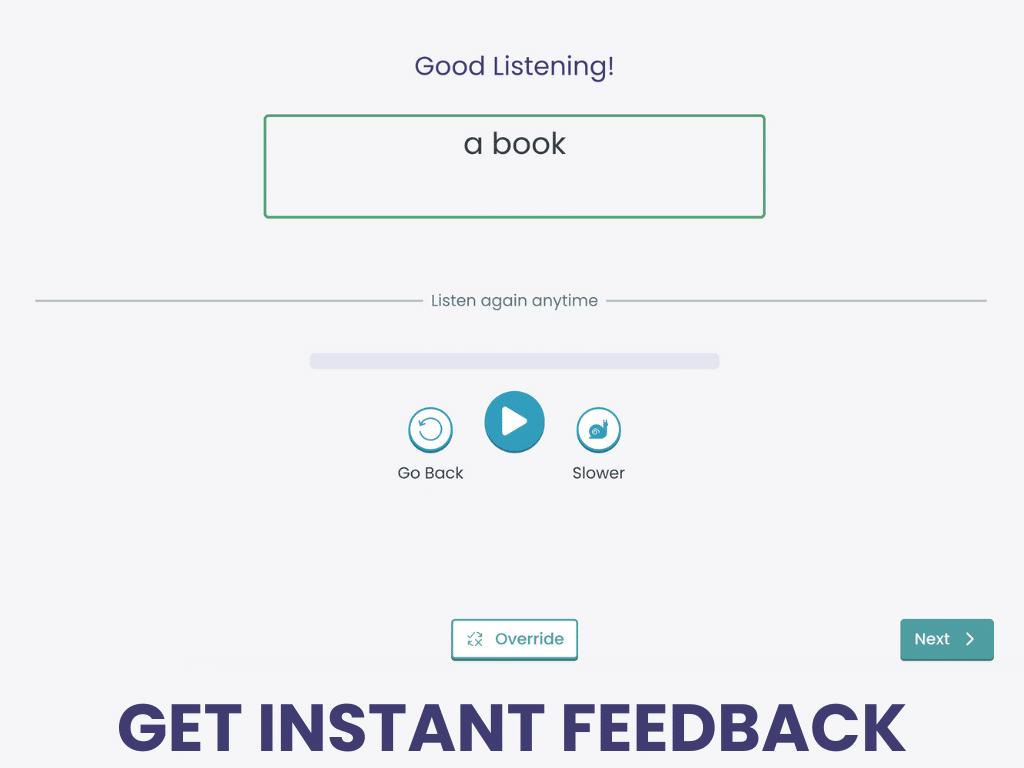

Everyday Listening Comprehension

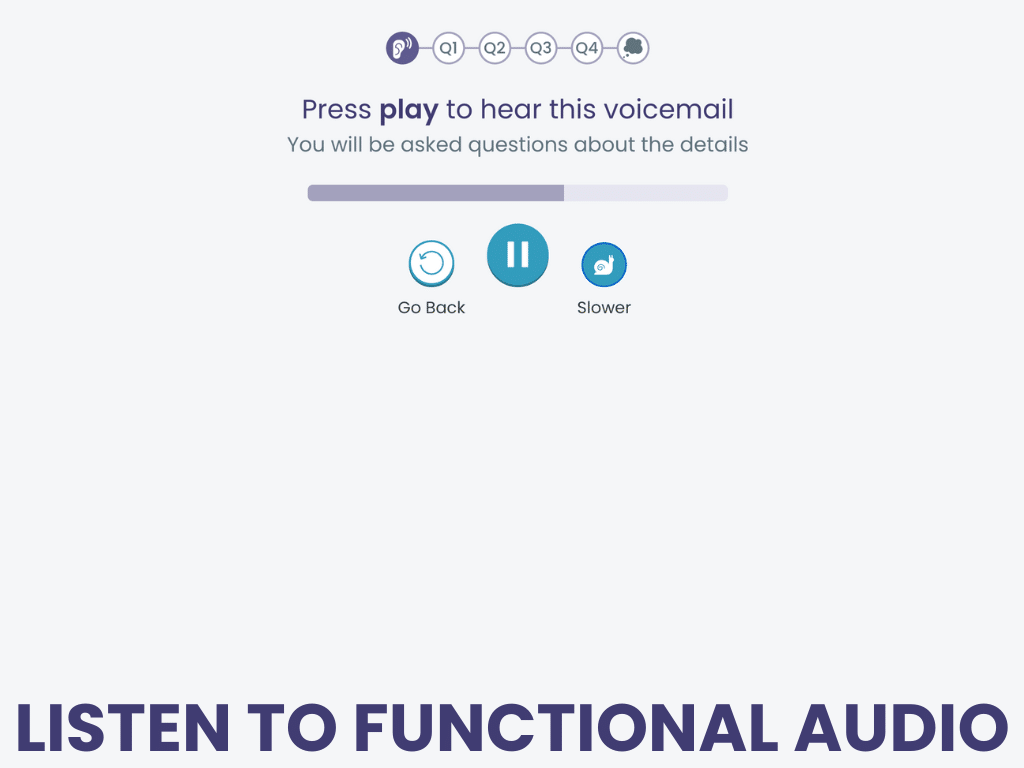

Everyday Listening Comprehension is a mixed treatment that uses functional, auditory stimuli of increasing length and complexity, like voicemails, radio ads, and podcasts.

Responses can be dictated or typed, allowing clinicians to target multiple language goals simultaneously.

Everyday Listening Comprehension is a listening treatment in the Tactus Virtual Rehab Center.

Sign up today for a risk-free 21-day trial of this innovative web-based therapy platform for SLPs.

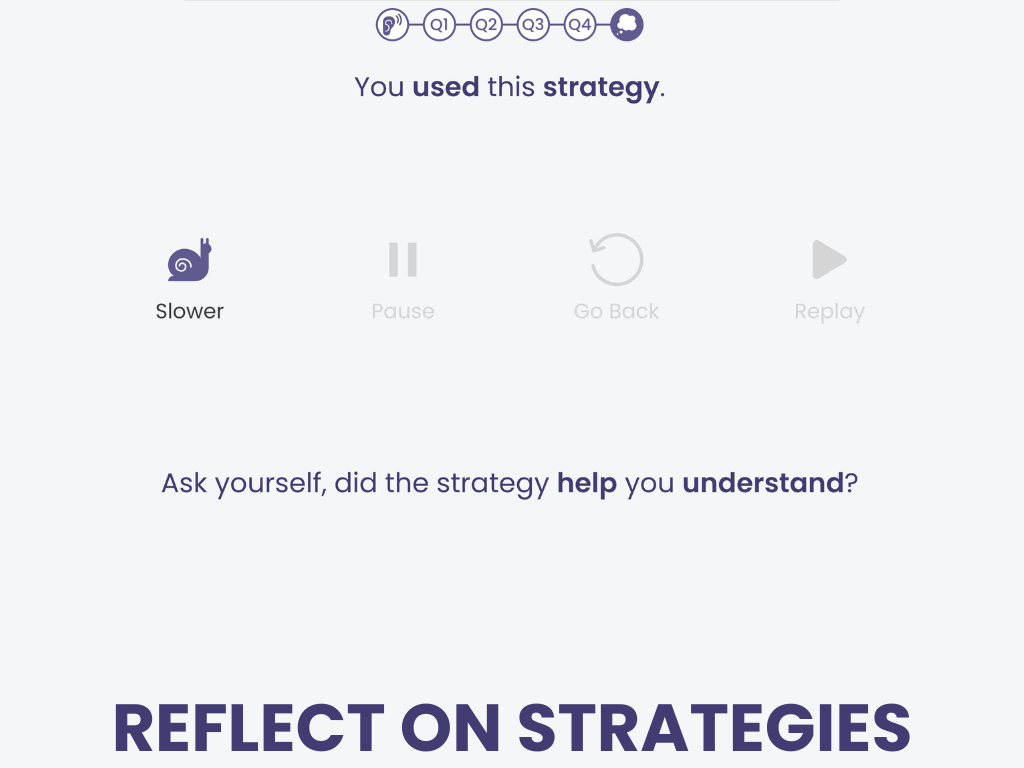

This treatment includes strategy teaching and reflection for a metacognitive component.

Compensatory Treatments

Conversation Partner Training (CPT) involves teaching family, friends, healthcare workers, and/or volunteers to use strategies when speaking to a person with aphasia. CPT can improve communication-related participation, emotional well-being, and overall functional communication (Shrubsole et al., 2022).

Read more about Conversation Partner Training in our How To: CPT guide

Common strategies to improve comprehension include:

- Use common vocabulary and short, simple sentences

- Avoid the use of pronouns whenever possible

- Augment speech with gestures, pointing, and body language

- Write keywords in large print as you speak

- Use visual aids such as drawings, pictures, or technology

- Check in to ensure the person has understood

- Control the environment: good lighting, minimal background noise, few distractions

- Have one-on-one conversations instead of in groups

- Time important conversations for when the person is most alert and focused

Remember that many people with auditory comprehension difficulties have learned to cover for their impairment by using context clues to predict what they’re likely to hear. If precise comprehension is essential, it’s always a good idea to provide visual and written supports to anyone who may have an auditory comprehension impairment.

Final Thoughts on Auditory Comprehension

Given how important auditory comprehension is to success in rehab and participation in daily life, it’s important for clinicians to look for impairments (both linguistic and cognitive) and treat them effectively. With the right interventions and support, people with aphasia can improve their auditory comprehension years after onset. Clinicians can use a combination of restorative and compensatory treatment approaches to meet the needs of each patient. Hopefully, there will be more high-quality research evidence in the future to guide us in the right direction.

Learning More about Auditory Comprehension

We used many references to bring you this information, all linked where they are cited. We recommend you read the original sources to learn more. This review is a good starting point:

Cite this article: Shahid, S. (2025, April). What SLPs Need to Know: Auditory Comprehension. Tactus Therapy. https://tactustherapy.com/auditory-comprehension-therapy-aphasia/